![]()

PART I

Religious Profile of Greece

An Overview Across Time

It should come as no surprise that I begin this overview of Greece’s religious cultures with a succinct summary of their underlying historical and systematic basics from antiquity to the present. This overview starts with the Hellenic and Christian religions, whose historical interactions form the main focus in part 2. It subsequently considers the rest of Greece’s religious scene, including important religious and cultural traditions, such as Judaism and Islam. In addition, it explores various marginal and minority religions, both broad movements and small groups, which were often controversial once (Orthodox) Christianity took hold and became predominant. Although there is a tendency to overlook these other religious branches, or to minimize their importance, they are an inseparable part of Greece’s religious history. To ignore them would obfuscate Greece’s religious variety and richness. My aim is thus to make evident the plurality of Greece’s religious scene, both historically and in the present.

Once we have examined the historical context, there are two other main focuses in part 1. First, to what extent and how did these religious cultures contribute to the formation or construction of Hellenicity/Greekness? The connection between religion and ethnicity/nationality has been a much-discussed and controversial issue in Greek history since Late Byzantine times. Naturally, this dual sticking point refers not only to Hellenism and Christianity but also to other religions. Second, how have all these religious cultures interacted with one another in history and what were the consequences of their mutual exchanges in the Greek context? This point is very pertinent to the complex and intricate relations among the predominant religious cultures and the rich array of other faiths. Answering these questions thoroughly enables us to adopt an integral view of Greece’s religious scene—its various trajectories, developmental lines, and concomitant changes in the long run. This approach does not look at religion in isolation but rather at the juncture of religious and sociocultural realms, from the political sphere and the intellectual domain to public and private life.

![]()

1

Hellenic Polytheism, Hellenism, Hellenic Tradition

There are many important reasons that would prevent us from doing this even if we wanted to. First and foremost there are the statues and temples of the gods which have been sacked and destroyed; it is necessary for us to avenge these with all our might rather than come to an agreement with the man who did it. Then again there is the matter of Hellenicity—that is, our common blood, common tongue, common cult places and sacrifices and similar customs; it would not be right for the Athenians to betray all this.

—Herodotus1

This was the Athenian answer given in 479 BCE to the Spartan envoys, who feared an alliance between Athenians and Persians. This categorical statement cited by Herodotus (484–ca. 425 BCE) reveals that, even then, there was considerable consensus among the Greeks as to what constituted “Hellenicity” (τò

λληνικ

ν)—namely a common Hellenic identity. He depicted common religious traditions, involving deities, temples, shrines, and sacrifices, as playing a crucial role. Herodotus’s witness is a strong one, but were things quite as he would have us believe?

No matter how one might consider Greek Antiquity, the rich and manifold tradition of Hellenic religion comes immediately to mind. This reflects long-standing, and more recently interdisciplinary, scholarly interest within academia. For example, scholar of Hellenic religion Walter Burkert, using a socio-evolutionary approach to Hellenic religion, derived sacrifice from hunting and then derived religion from sacrificial ritual.2 The frequently used plural form makes clear that Hellenic religion was not a single and static system3 but rather one that developed in various forms over time. The numerous surviving ruins of temples and sanctuaries in all possible locations (see fig. 1.1), even beyond Greece, testify to the wide appeal that Hellenic religion enjoyed in antiquity.4 When reading the long Description of Greece by the second-century pilgrim and author Pausanias, we get an image of all types of shrines scattered around Roman Greece. These included not only temples and altars but also natural surroundings, such as rocks, trees, and caves. In fact, Pausanias regarded Hellenic religion as the locus of common Hellenic identity under Roman domination.5

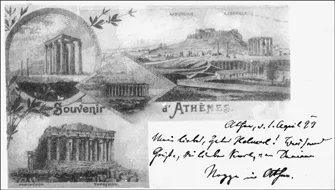

Fig. 1.1. A late nineteenth-century postcard of the type “Souvenir d’Athènes.” It depicts various surviving ancient monuments in Athens (Acropolis, Parthenon, Theseion, temple of Olympian Zeus). On this type of postcard, ancient Greek motifs usually predominated over the Christian ones, evidence of the significant upgrading of Greek Antiquity effected in the modern Greek state.

Historical Aspects

When did Hellenic religion begin to take shape? Because it possesses neither a specific founder nor a sacred book, it should be considered in the context of the modern periodization of ancient Greek history. Although Hellenic religion was basically formed in the context of the Greek city (π

λις,

polis) or city-state from the eighth century BCE onward, its roots should be sought in the antecedent periods (all dates being approximate):

the Minoan civilization (2700–1450 BCE); the Aegean Islands civilization, called collectively “Cycladic” (3300–2000 BCE); and the Mycenaean civilization (1600–1050 BCE), the first two being in all probability non-Greek. This is not meant to belittle the importance of later periods and their great achievements, but looking at earlier periods helps locate linking elements that were constantly reshaped afresh and gave rise to the Classical era. In fact, the ability of the Greeks to integrate the elements of various traditions into a new whole attests to the strength of their civilization.

The Minoan and Mycenaean contribution to historic Hellenic religion—a dearth of data makes it difficult to reconstruct the Cycladic religion—has attracted wide attention so far,6 although scholars now consider these cultures and their religious systems more on their own merits. Despite the lack of deciphered texts, we know that Minoan religion was polytheistic, featuring an elaborate pantheon and differentiation among deities; further, we know that Minoans engaged in sacrificial rituals and ceremonial banqueting, held sacred symbols, and built palaces as cult centers. There was also considerable contact between Minoans and Mycenaeans. This led to an overlap in religious beliefs and practices as well as mutual influences and exchange of deities (fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE). Mycenaeans created the first advanced civilization in Europe, consisting of several small, autonomous kingdoms, run by independent rulers and sharing common traditions, language, and religious customs. Since the decipherment of the Linear B tablets we know that Mycenaeans were the first speakers of the Greek language in its most ancient form.

Both religious cultures also had a lot in common with the religious environment of the Near East, which scholars have lately taken into greater consideration when examining ancient Greek civilization.7 Minoan cult practices, in particular cave cult practices, appear to have been influenced by Neolithic Anatolian cult practices. A vegetation cult of a fertile mother goddess was found in both Neolithic Greece and the East.8 Some of these traditions endured and passed into Classical Greece. Deciphered Mycenaean Linear B tablets include deity names both male and female,9 such as Zeus, Hera, Athena, Hermes, Ares, Poseidon, and Dionysus.10

Between the end of the Mycenaean period and the beginning of the historical era lie the “Dark Ages” of Greek Antiquity (1050–750 BCE), a period of obscurity because of the lack of written records. Yet, on the basis of archaeological evidence, older views about an isolated and stagnating “Dark Age” Greece have been significantly revised.11 In particular, the last phase of the “Dark Ages,” known as the Geometric period (900–750 BCE), was marked by socio-political upheavals, major cultural changes, trade links with the East, and decisive transformations (technical innovations and the adoption of a new alphabet after four centuries of illiteracy). It was a transitory yet crucial period for the later creation of a Greek world around the Mediterranean and the Black Sea through commerce and massive colonization. Earlier religious traditions were reshaped and new ones began to appear, including the new deities Apollo and Aphrodite.12 Many important cult centers (Delphi, Olympia, and Isthmia) arose around the eighth century. Initially, they functioned as open places with altars and as meeting places for sacrifice and communal meals, without any decisive architecture. The growth of more formalized worship there led to the building of temples, a fact that contributed to the supra-regional significance of these places. The oldest oracle in the Hellenic world was the shrine of Dodona in Epirus, which in historical times was devoted to Zeus.

During the Archaic period (750–490/80 BCE), Greek cities gained greater significance. Characterized by an aristocratic government overseen by various noble families, some situations turned into tyranny. One such instance was the reign of the Peisistratos family in Athens, overthrown in 510 BCE and followed by Cleisthenes’s reforms in 508/7 BCE. The Archaic period was marked by significant developments in commerce, handicraft, and social organization as well as by huge monumental activity, including the erection of temples with a standardized architectural form (700–675 BCE: first Doric temples; 700 BCE: rebuilding of Artemis’s temple on Delos; after 700 BCE: rebuilding of the Heraion on Samos; 580 BCE: Artemis’s temple on Corfu). The epics of Homer (second half of the eighth century BCE) and Hesiod (early seventh century BCE) provide evidence of a “pan-Hellenic” polytheistic theology (deities, heroes, and legends) alongside local accretions. As Herodotus noted, the poets Homer and Hesiod were the first to fix Greek notions of the genealogy of the deities (theogony), giving them their names, dividing honors and functions among them, and designating their forms.13 At the intellectual level, the Pre-Socratic philosophers (sixth and fifth centuries BCE) were the first to look for rational explanations of natural phenomena, combined with a critique of mythological religion and especially of crude beliefs about nature.

Characteristic of this period is the appearance of specific aspects of Hellenic religion that exceeded local boundaries and constraints, which, however, never ceased playing a role. The formation of the pantheon of twelve deities (Δωδεκάθεoν), who were believed to reside on Mount Olympus—the composition of their group never firmly fixed—and were headed by Zeus, bears witness to a central outlook that acquired pan-Hellenic significance. At the same time, numerous attributes were ascribed to the Olympian deities in the context of local worship, which demonstrates the continuous dialectic between the local and the trans-local in Hellenic religion. It is also in this period that certain sacred places were elevated to supra-regional and even pan-Hellenic centers.

The first of these was Delphi (eighth century BCE) with the oracular sanctuary of Apollo, known for its patronage of colonization and granting

συλ

(neutrality and exemption from attacks) to certain cities later on. The Pythian Games took place there every four years starting in 582/81 BCE. The oracle of Delphi, the most important in the Classical world, also became a locus of contention, as various religious wars over its control show (595–583, 448, and 356–346 BCE). A second sacred place was Olympia, where the first Olympic Games to honor Zeus, conventionally assumed to date back to 776 BCE, took place every four years. Similar meeting places were the Isthmian Games (on the Isthmus of Corinth), held every two years from 581 BCE onward to honor Poseidon, and the Nemean Games (at Nemea) honoring Zeus from 573 BCE onward, also held biennially.

All this continued into the Classical era (490/80–323 BCE), marked by military confrontations between Greeks and Persians, events that contributed significantly to a common Hellenic identity. It was also a time when the city of Athens, owing to its magnitude, naval power, democratic governance, and cultural achievements, became the preeminent city in Greece. The monumental construction of the Acropolis, featuring the temple of Parthenon at its peak, was to render this city famous in antiquity and beyond. A large portion of our knowledge of Hellenic religion derives from Athenian religion, thanks to the existence of ample documentation—literary, artistic, archaeological, and epigraphic—from this culturally fecund era.14 It was a period when worship and ritual, both local and trans-local, became more systematized. Increased reflection on religious matters also led to critiques of traditional mythological religion, induced by the development of institutions of learning and philosophical schools. Philosophical critique of religion, as well as the introduction of novel ideas, sometimes produced strong reactions and led to condemnations, as in the case of Socrates (470–399 BCE) and the Sophists. The end of the Classical era was marked by the increased role of the Macedonians in Greek affairs, leading to the control of southern Greece by King Philip II (r. 359–336 BCE). His son, Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BCE), continued his plan and led the successful Greek campaign against the Persians, which contributed to the spread of Hellenic culture and language from the Near East to India and later to the development of centers of Hellenic culture outside the Greek mainland, such as Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamon.

Alexander’s death initiated th...