![]()

One

A Troubled Community

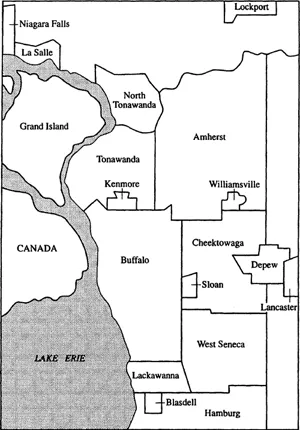

Buffalo, the self-proclaimed Queen City of the Great Lakes, entered the 1920s well-established as a major urban center. Scores of churches, a progressive public school system, three colleges, a university, a fine arts academy, museums, libraries, and concert halls attested to the city’s rich spiritual, educational, and cultural life; dozens of charitable, social, and professional organizations and a municipal government that employed nearly eight thousand workers likewise indicated an advanced stage of urban development, as did the modern office buildings and hotels that dominated the downtown skyline.1 The federal census for 1920 placed the local population at 506,775, certifying Buffalo as the eleventh largest municipality in the United States, and by 1925 the number had increased to just over 538,000. When the rapidly expanding populations of nearby communities (see figure 1) such as Lackawanna, Tonawanda, Lancaster, Cheektowaga, West Seneca, and Amherst are considered, the number of residents in the greater Buffalo area was approximately 580,000 at the beginning of the decade and more than 640,000 five years later. In few previous periods had future growth and prosperity seemed more assured, city planners confidently predicting that the metropolitan population would exceed two million by 1950.2

Figure 1

Buffalo and Nearby Communities circa 1920

This optimism rested in large part on a recent and remarkable upsurge in local industrial production. In 1919, the total value of manufactured goods produced in Buffalo was $634,409,733, an increase of 256 percent over the total for 1914. Benefitting from electrification, modernized facilities, and better management, almost all of the city’s chief industries were achieving unprecedented output by 1920: within a five-year period, flour milling production had increased by 137 percent, meat packing 115 percent, foundry and machine products 184 percent, and automobile bodies and parts 414 percent; similarly impressive gains took place in the steel, chemical, furniture, and tanning industries and in many smaller sectors of the economy, with the result that the Commerce Department ranked Buffalo as the eighth largest manufacturing center in the country.3

Industry and manufacturing, conducted in a vast ring of factories and plants that circled within and just beyond the city limits, constituted the chief source of Buffalo’s growth and prosperity, but other forms of economic activity were also important. The city was second only to Chicago as a commercial shipping center in the 1920s; over five hundred freight trains arrived and departed daily, and each year millions of tons of bulk commodities passed through the port. Local trade with Canada steadily increased throughout the decade, and the wholesale marketing of coal, lumber, machinery, food products, and automobiles experienced unprecedented expansion. Commercial banking also grew rapidly, more than sixty branch banks being opened between 1916 and 1926. The profits of industry and commerce—distributed in the form of more jobs and higher wages—in turn sustained a burgeoning retail economy that employed over thirty thousand workers by 1929.4

Economic advancement depended, of course, upon people. In 1920, Buffalo’s working population—proprietors, self-employed professionals, salaried employees, and wage-earners—numbered 215,323. More than three-quarters were white males, but the percentage of women and blacks was gradually increasing. Just under 46 percent of all workers were engaged in manufacturing and industry; 26.1 percent held clerical positions or were involved in trade, and 17.1 percent held jobs in public, professional, personal, and domestic service; most of the remainder worked in transportation. Over the course of the decade, this distribution changed somewhat, but industry and manufacturing remained the largest sources of employment.5

The prejudices and social customs of the period inevitably influenced the occupational status of certain groups within the working population. African Americans were more likely to hold low-status jobs than whites and females were more concentrated in low-manual, semiskilled, and service employment than males. Among white workers, those who were native-born and of native parentage enjoyed the highest overall status, approximately half holding nonmanual positions in 1920; in contrast, only 22.8 percent of foreign-born workers filled nonmanual roles.6

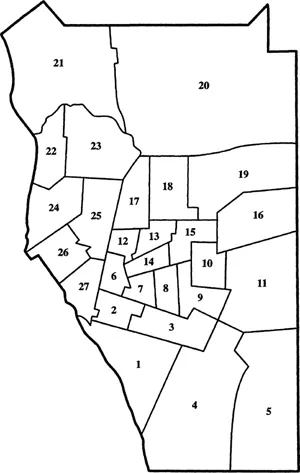

Socioeconomic disparities among the work force were well reflected by Buffalo’s residential development. West of Main Street, within the boundaries of the Twenty-Fifth Ward (see figure 2), resided many of the city’s most prominent business and professional people; here, along beautiful tree-lined boulevards such as Delaware Avenue, the wealthy and near-wealthy lived in homes as elegant as any in the United States. To the north, near the Chapin, Bidwell, and Lincoln parkways in the Twenty-Third Ward, were other affluent neighborhoods. These elite districts were located in wards with the highest percentage of native whites of native parentage in the city. Less exclusive, middle-class residential areas—the eastern sections of the Twenty-Second and Twenty-Fourth Wards on the west side; the North Park, Central Park, and Kensington districts in northeast Buffalo; new housing developments near the Humboldt Parkway on the upper east side; and south-side neighborhoods along South Park Avenue—were also characterized by large native-white-of-native-parentage populations, although residents were more likely to be of German and Irish ancestry that was the case in the most prestigious wards.7

While middle-class Buffalonians tended to reside in outlying areas, those of lesser means were concentrated in the more central and congested parts of the city. As in previous decades, the poorest wards were on the lower west and east sides, where, amid the noise and pollution from nearby railroads, factories, and stockyards, residents endured substandard housing and the other problems typical of low-income neighborhoods. The populations of these inner-city districts contained the highest ward-level percentages of foreign-born whites in Buffalo, matched only by the heavily industrialized Twenty-First Ward in the northwestern part of the city.8

Two important facts concerning the foreign born in the 1920s should be stressed. First, as a group, they were a declining element in the city; in fact, as immigration restriction went into effect, their numbers shrank for the first time in decades, from 121,530 (23.9 percent of the total population) in 1920 to 118,941 (20.7 percent) in 1930. Second, the foreign born had attained an unprecedented degree of national and ethnic diversity. Poles (6.2 percent of the city population), Germans (4.1 percent), Italians (3.2 percent), Canadians (3.1 percent), Irish (1.4 percent), and English (1.3 percent) composed the largest local groups in 1920, but there were sizable contingents from many other countries. Over the course of the decade, most of the non-English-speaking nationalities experienced a decline in numbers, with the exception of Italians, who increased by 19 percent. At the same time, the combined number of immigrants from Canada and Britain rose by nearly 27 percent.9

Figure 2

Location of Buffalo Wards

Residing with, among, and near the foreign born were many native-born ethnics of foreign, mixed, and native parentage. Wards in the heavily Polish, Italian, German, and Irish parts of the city included the highest percentages of second-generation ethnics, but even in the elite districts nearly a third of the native-born white residents had at least one foreign-born parent. Published federal census data do not reveal the precise ethnic composition of ward populations in 1920, but reliable estimates for several major ethnic groups can be culled from manuscript census returns. These percentages indicate that Buffalo can be viewed as being roughly divided into six ethnic zones: a heavily Irish south side, a Polish lower east side, a German upper east side, an Italian lower west side, a large Anglo-American district encompassing the upper west side and the northeastern part of the city, and an ethnically diverse—Polish, Anglo, and German—sector to the northwest.10

Race also divided the community. By 1920, there were nearly five thousand blacks in Buffalo, most of whom lived in the Sixth and Seventh Wards on the lower east side, one of the most impoverished parts of the city. As elsewhere in the United States, local African Americans confronted racist attitudes that severely limited socioeconomic mobility. In a study conducted in 1927, University of Buffalo sociologist Niles Carpenter discovered that many city employers considered blacks to be “slow thinkers” who were “not able to assume any responsibility”; most of those interviewed agreed that blacks “should always have a white man as foreman.”11 With such sentiments prevailing, it is not surprising that the large majority of black workers were confined to low-paid unskilled and semiskilled jobs and that their status improved only marginally during the 1920s. Buffalo’s African-American population did include, however, a number of talented business and professional people who spearheaded efforts on behalf of racial improvement and expanded civil rights; voicing their opinions in the black-owned Buffalo American and working through such organizations as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, these leaders kept a close watch on developments that might threaten their community.12

Religion supplemented race as a source of potential conflict in Buffalo in the 1920s. According to federal census data, just under 64 percent of all city church members in 1926 were Roman Catholic; Protestants, in contrast, composed only 27.8 percent of those affiliated with a particular church, while Jews constituted less than 6 percent. These figures probably exaggerate the extent of Catholic dominance somewhat, because many Protestants did not belong to a specific denomination; but—just on the basis of the large number of residents of Irish, Polish, Italian, and German ancestry—it seems virtually certain that a majority of Buffalonians were Roman Catholic.13

As an institution, the Catholic Church was one of the largest, wealthiest, and best established organizations in Buffalo. It maintained eighty-four churches and sixty-two parochial schools, published its own newspaper, and owned hundreds of acres of valuable real estate throughout the city. Under the leadership of a series of politically astute bishops, the Buffalo Diocese had forged a close relationship with local political and business leaders, earning gratitude for its strong stand against socialism and other forms of “radicalism.” The church remained a force for social conservatism throughout the 1920s, its clergymen regularly denouncing divorce, marital infidelity, birth control (“race suicide,” one priest termed it), the erosion of traditional family life, and a perceived abandonment of Christian ideals.14 Catholics, therefore, occupied common ground with Protestants on many social issues. Differences over controversial matters such as prohibition, however, kept traditional suspicions and animosities fully activated.

Local politics in the 1920s reflected the generally conservative orientation of most Buffalonians. Throughout the decade, despite rising ethnic tensions, the large majority of voters enrolled as Republicans; even in 1924, when controversy over the Ku Klux Klan threatened to explode into open religious warfare, over 64 percent of the potential electorate affiliated with the party of Lincoln. As had long been the case, partisanship demonstrated a close relationship with ethnicity in Buffalo. Average Republican-enrollment percentages for the period 1922-1924 (the time when the local KKK was most active) show that Republican strength was below 50 percent in only eight wards—all located in the heavily Irish and Polish parts of the city—while Italian, German, and old-stock wards had sizable Republican majorities. The large Republican following in wards on the upper east side is of particular interest because it strongly suggests that significant numbers of German Catholics had abandoned their longtime support of the Democratic party.15

Not surprisingly, given enrollment figures, the Republican party won presidential elections in Buffalo throughout the 1920s. Warren G. Harding carried the city with a landslide 63.4 percent of the vote in 1920, and four years later Calvin Coolidge received 57.2 percent in a three-way race; in 1928, Herbert Hoover narrowly prevailed over New York Governor Alfred E. Smith.16 In state and local races, however, the electorate was far more unpredictable. The fortunes of Al Smith provide a good case in point. In his successful 1918 race for governor, Smith failed to carry Buffalo, and in 1920 he was handily defeated in the city by Nathan L. Miller. Two years later, emphasizing his opposition to prohibition, Smith trounced Miller locally, only to be soundly defeated in 1924 by Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.; in 1926, Smith narrowly carried the city in a contest with Ogden L. Mills.17 As the governor’s ups and downs in local polling well demonstrated, the intermingled and ever shifting influence of religion, ethnicity, party, and class resulted in a very complex and volatile political situation. This was even truer at the municipal level, where diverse interests converged with particular intensity. Because the events that were taking place in city politics played such a crucial role in shaping the local Klan experience, they should be examined in some detail.

· · ·

The aspirations and attitudes of Buffalo’s large population of recent immigrant stock were well represented by the controversial individual who would dominate city government for most of the 1920s. Born on Buffalo’s east side in 1874, the son of poor immigrant parents from Austria and Bavaria, Francis Xavier Schwab scarcely seemed destined for civic prominence. Shortly before completing his elementary education, Schwab went to work as a tinsmith’s apprentice, later claiming that his real education had come in the “school of experience and in the university of hard knocks.” Over the next decade, Schwab worked for a number of local industrial firms, then changed careers and became a salesman for the Germania Brewing Company. Hardworking and naturally gregarious, Schwab soon established himself as a popular figure among local tavern keepers and restaurateurs, many of whom were fellow German-Americans; he also was active in the Knights of St. John, a German-dominated Catholic men’s group similar to the Knights of Columbus. Several years later, Schwab utilized his contacts and expertise to secure a position as manager of the Buffalo Brewing Company, which later became the Mohawk Products Company, one of Buffalo’s most prominent breweries. In the interim, he assumed the joint position of president and general manager, thereby completing an impressive rise in the world of business.18

By this time, Frank Schwab had developed a personal style that delighted his friends and infuriated his enemies. A tall, lean man with a dark moustache, always dapperly attired with his silk tie adjusted in a distinctive “submarine” fashion beneath his collar, he delighted in being the center of attention; noontime would typically find him in a local saloon or cafe, surrounded by cronies and holding forth on a variety of topics in his heavily accented English. Ever ready with an encouraging word, a friendly smile, or a small cash handout for the less fortunate, he considered himself to be a special friend and representative of the common people. Such populistic sentiments, however, were largely unrelated to any type of coherent political philosophy or partisan orientation. Although nominally a Republican, Schwab was in actuality an independent who remained free of links to profes sional politicians, being motivated more by cultural issues and the pursuit of personal power than any desire to ingratiate himself with the political establishment.19 He constituted a wild card on the local political scene, one who only came to power because of the unusual opportunities created, ironically, by ...