![]()

1

Welcome to East New York

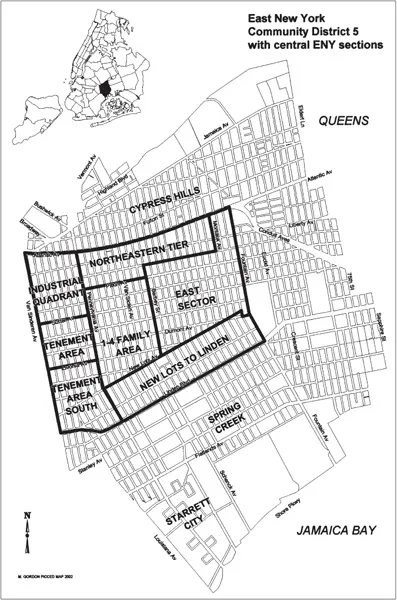

THIS CHAPTER INTRODUCES East New York as it appeared to my consulting firm late in 1966–67 (see map 1).1 At the start of the 1960s, the population was 85 percent white. By the end of 1966, the population of 100,000 was close to 80 percent black and Puerto Rican. Hundreds of small businesses closed during the changeover; churches and synagogues were abandoned, then vandalized and burned before they could be put to use by the incoming population. Public services and private agencies were unprepared (and often unwilling) to address the needs of the new minority population.

What brought the community to its sorry state is a story with many threads. This chapter describes where, under what local circumstances, and to what extent the transformation from white to minority took place.

In 1966, central East New York was a major community, its 100,000 people formed into 29,500 households.2 Some 45 percent of the population lived in female-headed households, only one member of which was an adult. Racially and ethnically, there were close to 48,000 blacks, 30,000 Puerto Ricans, and 22,000 whites. Of the 29,500 households, about 6,000 (equal numbers of blacks and Puerto Ricans) with an average of five persons per household were on welfare, with another 5,500 households with an average of three persons per household (80 percent black and 20 percent Puerto Rican) were eligible for welfare but not on it. Many eligible households that applied were illegally denied welfare benefits.3 It is also intriguing that a female-headed household with fewer than three children was normally not on welfare, while a mother with three or more children usually was.4 However it was sliced, 40 percent of East New York households were living in poverty.

Not everyone in East New York was poor. In addition to the 11,500 households on welfare or eligible for it, there were approximately 8,000 homeowners, with an average household size of three persons. Fewer than 40 percent of the homeowners were white, three-quarters of whom were Italian; 45 percent were black, and the remaining 15 percent were Puerto Rican. The rest of the population, some 10,000 renter households, were equally split between white middle- and working-class tenants, 75 percent Italian, 25 percent Jewish, with equal numbers of working-class blacks and Puerto Ricans.

There were large numbers of children and teenagers in the community, resulting in less adult and especially parental control. The average age in East New York was under eighteen years compared with twenty-five to thirty-five years in most stable New York City communities. Of roughly 55,000 persons under eighteen years of age, 25,000 were enrolled in public schools and 7,000 in private schools; 18,000 were in the preschool ages or out of school. Leaving aside the prekindergarten age group, my firm’s analysis indicated that some 9,000 school-age children and teenagers were not attending school.

One out of every seven youths between the ages of seven and twenty was arrested during 1965. In 1966, seven crimes were reported for every 100 persons in the area.

In East New York’s tenement area alone (see description later in this chapter), with only 16,000 people, there were more than 1,000 juvenile delinquents in 1965.5 Some 400 fires and more than 1,100 crimes (about a quarter of those that actually occurred) were reported in this area. In East New York as a whole, there were 1,400 fires in 1965, 400 of them in vacant buildings. Young people used vacant buildings as clubhouses, and dope addicts set up housekeeping in them; fires started to keep the occupants warm often got out of control. Such fires were dangerous to adjoining buildings as well as to squatters in the vacant buildings, and caused more than one fatality during the course of the study. Violence, shootings, knifings, and gang terror were common.

HOW EAST NEW YORK GOT ITS NAME

The first major event in East New York’s history was its settlement by the Dutch in 1690.6 Called the New Lotts of Flatbush, the area was developed into ten farms owned by the different families such as the Schencks and the Van Sinderins, for whom many East New York streets are named. The New Lots Reformed Church, now a landmark, was first established in the seventeenth century and rebuilt in 1824.

A second major event was the appearance of Colonel John R. Pitkin. Arriving in New Lotts in 1835, with money and ambition accrued as a Connecticut merchant, he beheld a farming district little different from the Dutch settlement it had been 150 years earlier. What he envisioned for the area, however, was consummately urban. On the land then given to potatoes and wheat, dairy cows and swine, a land known as “the Market Garden of the United States”, he wanted to build factories, shops, homes, and schools.7 To make clear what he had in mind, he named his new settlement East New York.

He bought 135 acres of land from farmers in the area, built a shoe factory on one parcel, and divided the rest into lots that sold for ten to twenty-five dollars each. He named the first new thoroughfare Broadway. The financial panic of 1837 ended Pitkin’s dream of metropolitan grandeur, reducing him to serving as the auctioneer of his own assets. But he was not without a legacy. Broadway came to bear his name: Pitkin Avenue. The shoe factory and the workers who built cottages around it spearheaded the area’s shift from agriculture to industry. The designation “East New York” supplanted New Lotts on maps and in official records.

Through the remaining decades of the nineteenth century, East New York grew gradually through the talents and hard work of German immigrants as brushmakers, gold-beaters,8 and tailors. With the installation of five electrified subway and trolley lines between 1880 and 1922, a genuine boom began. Many new-law tenements were built.9 From Manhattan’s Lower East Side and the older Brooklyn district of Bushwick streamed Italians and Jews, Russians and Poles, filling the new tenements and locating inexpensive home sites between the Jamaica Avenue El on the north and the Livonia Avenue trestle to the south. The immigrants bottled milk, brewed beer, stitched clothes, and cast dies. Manning factory assembly lines, they made products ranging from starch to fireworks, toys to torpedoes.

In 1906, the Williamsburg Bridge opened—the “Jewish Passover” to Brooklyn. Jews emigrated to Williamsburg, and some found their way to East New York. Other East European immigrants, Poles and Lithuanians, joined the influx. Italians, in much smaller numbers, acquired truck farms from the remaining Dutch. Some Italians became marshland squatters and later went into the private refuse-disposal business.10

By the Great Depression of the 1930s, East New York was completely built up north of New Lots. It was a stable, lower middle-class community, heavily Italian Catholic and Jewish, with a large enclave of Polish Catholics centering around St. John Cantious Church. There were also a number of well-to-do Dutch families that still owned substantial property and had strong attachments to the community. Churches, synagogues, and schools were all built during the pre-depression period, but little was constructed during the depths of the depression.

THE INDUSTRIAL QUADRANT

The transition from white to black and Puerto Rican started in the northwest quadrant, in Colonel Pitkin’s part of town (see map 1).11 More than half the area was in industrial or commercial use; the housing was concentrated in only a few blocks. The older housing stock was made up in good part of nineteenth century old-law frame dwellings, as well as two-family frame dwellings that had been converted to multiple dwelling use. By the early 1950s, the housing stock had markedly deteriorated. Houses stood next to vacant buildings, garbage-strewn lots, junkyards, and automotive body works, creating an oppressive atmosphere. Industry and commerce appeared to thrive, however. Many companies were planning to expand, including several that had recently acquired additional properties. The area also contained the smallest number of public or semipublic facilities such as schools in East New York, and only one community improvement group was identified.

As might be expected, after World War II, many tenement dwellers from this northwest quadrant sought to improve their standard of living. As the suburban boom took hold and the postwar housing shortage eased, there were successive shifts of the white population from poorer to better housing. Industrial-quadrant families began moving into single- and two-family homes east of Pennsylvania Avenue. They were replaced initially by whites and a few blacks and Puerto Ricans who settled in the community. All seemed normal, as retired couples living in the tenement area to the south held on to their houses in the face of rising housing costs elsewhere.

As whites continued their exodus, more blacks and Puerto Ricans moved in. In a gradual progression, over a period of fifteen years, the industrial quadrant became the first section to change completely in ethnic composition. By early 1966, the area had become 90 percent black and Puerto Rican.12 The shift caused little concern in the adjoining white community, largely because the area was a mixture of housing and industry and somewhat isolated from the main residential community.

THE TENEMENT AREA

The tenement area, the focus of the city’s Vest Pocket Housing and Rehabilitation Program, for which my consulting firm did the planning, lay just south of the industrial quadrant. It was heavily built up, with four-story tenements, both old-law and early new-law, with mostly small apartments. The area contained a substantial number of two- to four-family houses, as well. Building maintenance had been neglected since the beginning of World War II; landlords continued their neglect after the war’s end, complaining bitterly about New York City’s rent control laws all the while.

As with residents of the industrial quadrant, dissatisfied younger families began to move out of the tenements, not only to housing east of Pennsylvania Avenue but also to residences south of Linden Boulevard, to Canarsie, to Queens, and even to Long Island. In many of these areas, a home could be had for less than a thousand dollars down. A major new rental housing development, Warbasse Houses, was built in Canarsie and proved very attractive to older Jews and other religious and ethnic groups. This was followed in the early 1970s by Starrett City in the Flatlands.

Population pressures on East New York were intense. To the north, the Bedford-Stuyvesant ghetto had been developing rapidly during and since World War II; Brownsville had already become a completely devastated black ghetto. Concurrently, the New York City Housing Authority began displacing several thousand additional Brownsville families for a series of massive public housing projects, adding greatly to the pressures on adjoining areas.

These thousands of families and other thousands spilling out of the expanding Brooklyn ghettos joined in the desperate search for housing. They scoured the streets of East New York looking for apartments. With few whites interested in renting, landlords began renting to blacks and Puerto Ricans at the higher rents permitted when apartments became vacant. Some even harassed their old white tenants, getting them to move so that they could rent to blacks at higher rates. As whites moved away, more blacks and Puerto Ricans moved in. The growing white departure yielded new vacancies, swiftly taken by friends and relatives of the blacks and Hispanics already there. Further, welfare and social agencies were also busy seeking housing for their clients, adding to the social and economic pressures.

By 1963, most young, white families had left the tenements; only elderly people and a few others were left. The streets were already undergoing a transformation. Practically every block showed at least one boarded up or burned-out building; some showed as many as three or four. Sanitation services were neglected; the streets began to fill with garbage and broken glass. Move-ins and move-outs were common, especially among welfare clientele, lending an aura of instability to the area. Black and Puerto Rican children and youths dominated the landscape; growing lawlessness, vandalism, and violence made the streets unsafe. The Jewish community panicked; many moved south of Linden Boulevard, leaving behind abandoned synagogues and community centers. Jewish and other ethnic shopkeepers, frightened by vandalism and crime, isolated from their old customers, also moved out of the area. Many others were wrenched loose by real estate speculation, robbery, and racial tension.

The first of two riots in the summer of 1966 helped complete the tenement area’s transition to more than 90 percent black and Puerto Rican. The unrest was traced to turf conflicts between black and Puerto Rican youths. Hundreds of black, Puerto Rican, and white households immediately fled the area, touching off a wave of vandalism and crime that lasted well into the winter months of 1967.

TENEMENT AREA SOUTH

South of the tenement area, there was an almost complete changeover from white to black and Puerto Rican between 1960 and 1966, but with far less destruction. About half the structures in this area were one- to four-family dwellings, many of which were bought by minority families after 1960, largely due to sales promoted by “blockbusting” speculators. A substantial percentage of the new owners rented rooms to welfare families, thereby raising the population densities above their 1960 levels. The rest of the housing was in four-story walk-up brick tenements, which had also lost most of their white tenancy.

Most of the area required only minor maintenance, though one out of every four or five blockfronts could have used moderate rehabilitation. There were relatively few vacant buildings as well; one or two were noted on a few blocks bordering the tenement area. South of New Lots Avenue, one or two vacant buildings per blockfront were also found.

The Jewish and Italian residents who remained were unhappy about the minority in-migration and were worried by the increase in fires and crime. Sanitation was poor; some streets close to the tenement area were littered with broken glass. Block associations and the East New York Owners and Tenants League worked hard to maintain the area, but many owners became pessimistic about their investment. There were few public facilities, few churches, and some infrequently used synagogues.

THE NORTHEASTERN TIER

This area experienced the lowest rate of population turnover in East New York, at least until 1967. While the tier’s population had aged, my firm estimated that the ethnic composition remained predominantly white and the household size relatively stable. Aside from the heavily commercial Atlantic Avenue frontage, the area was residential. Dwellings were predominantly frame structures housing one to four families. While a good many buildings had been well maintained, their owners continuing to paint and otherwise keep up their property, many buildings had deteriorated through their owners’ neglect.

Recent events had also taken their toll. Vacant buildings were liberally scattered throughout the area, but rarely more than one to a block. Yet, the depressing effect of these vacant and vandalized buildings, taken together with the few vacant lots overgrown with weeds and a general air of neglect, contributed to the pessimistic outlook of many residents.

One new public school was under construction, and another had been approved. There were other public facilities, including several substantial churches, parochial schools, and related facilities. The Russian Orthodox Church was a community landmark, and St. John Cantius Church (located just south of the Northeastern Tier boundary) was a major institution. St. John’s Lutheran Church, a very old community institution, was also located there. Rising crime rates and antipathy toward the minority families living in pockets of deteriorated housing had dulled the sense of satisfaction occasioned by the new schools. At community planning meetings, many businessmen were thinking of closing their stores. The area seemed susceptible to considerable deterioration and change over the coming years.

THE ONE- TO FOUR-FAMILY AREA

In a sector of almost fifty square blocks, running from Pennsylvania Avenue east for half a mile, there was a large number of one- to four-family homes, many of which had been purchased by minority-group families as a result of blockbusting (see chapter 3 for more detail). The minority groups replaced a largely Jewish population, which moved south of Linden Boulevard or to the suburbs in the early l960s. In 1967, my firm estimated the racial composition at 50 percent black, 30 percent Puerto Rican, and 20 percent white.

A number of white homeowners held out east of Pennsylvania and north of New Lots, but no new white families moved in; the blockbusting brokers saw to that. Most homeowners had to accept welfare tenants in their two- to four-family houses to keep the units occupied so that they could keep up with mortgage payments. According to owners, exploitative real estate practices, including onerous mortgage terms and shady home improvement schemes, operated here with devastating effect.

Nevertheless, the area was in better shape than might be expected, considering its proximity to the tenement area. This was at least partly a result of its lower densities and its amenities such as Linton Park, the Thomas Jefferson High School field, and the New Lots Branch Library. There was little mixed use, and only a few apartment buildings. The housing was more solidly constructed, the row-house facades often faced with smooth, light tan brick that resisted wear and discoloration. There were some vacant buildings, but these were scattered. Newly organized block and community organizations were active.

The second riot of 1966 was a battle that pit black and Puerto Rican youths against Italian youths. The Italians held their ground. Less than a year later, in mid-June 1967, a yout...