![]()

1 Detachment

The Caning of James Gordon Bennett, the Penny Press, and Objectivity’s Primordial Soup

On a sunny spring day in 1836, James Gordon Bennett left his newspaper office to begin his morning perambulations around Wall Street, seeking information for the financial column of his new one-cent paper, the New York Herald. That morning, as he roamed the narrow, tortuous streets of the financial district, Bennett might very well have been counting his blessings. He was a man on the rise. In part because of his coverage of one of the most sensational crimes of the century—the ax-murder of a beautiful prostitute—his paper, which he had started a year before with a five-hundred dollar investment, was quickly becoming one of the most successful newspapers in New York.1 Bennett even boasted that his paper had the highest circulation in the world. Indeed, the Scottish-born Bennett, who had single-handedly sold the ad copy, reported events, wrote the columns, and edited the newspaper, was now in a position to advertise for help: “A smart active boy wanted, who can write a good hand.” Bennett also called for “a new corps of Carriers” to augment the growing army of those who hawked his paper. Bennett was a rare example of the total fulfillment of the American Dream, a man who could hardly keep up with his own success. It was on this brilliant spring morning that a rival editor, James Watson Webb, caught up with Bennett on Wall Street, shoved him down a flight of stairs, and beat him severely with his cane.2

Why Webb beat Bennett has never been explained beyond the former’s penchant for violence and the latter’s obnoxious character. It is true that in the weeks before the beating, Bennett’s columns had included numerous jabs at Webb, the editor of New York’s best selling newspaper, the staid and elitist Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer.3 “We are rapidly taking the wind out of the big bellied sails of the Courier & Enquirer,” wrote Bennett, poking fun at his rival’s rotundity and the dimensions of the Courier’s large news sheet. Bennett promised that the Herald would ultimately best the “bloated Courier” (italics mine). In the weeks before the assault, Bennett also called Webb a “defaulter” who was guilty of “disgraceful conduct,” and offered to send him a piece of the dead prostitute’s bed as a “momento mori.”4 But Webb was not the only editor Bennett addictively insulted; one of Bennett’s biographers pointed out that he “managed to attack in a single issue seven newspapers and their editors.”5 While other editors returned Bennett’s verbal abuse or simply ignored it, Webb beat Bennett—three times, in fact, in 1836. So why did Webb resort to violence while others abstained? This chapter examines the rise of the first “independent,” nonpartisan press through the prism of Webb’s conflicts with Bennett. In doing so, this chapter grapples with the birth of “objectivity’s” first element: detachment.

It is fitting that we begin our look at “objectivity” with an examination of the early “independent” press, the first American newspapers to detach themselves from political parties. How and why the popular, nonpartisan press arose in the 1830s is the focus of this chapter.6 I also explain how Bennett represents a departure from Webb’s brand of journalism, a departure that reflected an increasing detachment on the part of journalists. This is a step toward what journalists call “objectivity.”

In order to discuss detachment, however, we must first consider the conditions that brought about its birth. How did this new kind of journalism evolve? As I will discuss, journalism historians have long maintained that the popular press of the 1830s came out of “Jacksonian democracy” in much the same way as Athena was born from Zeus’s head: springing out fully formed. But while journalism historians see the birth of modern journalism as a natural outgrowth of a benign and democratic period, other scholarship would suggest that modern journalism grew out of a violent and inegalitarian era. Why is this important? Because detachment was never as clear as when the first commercial press of the 1830s detached from the violent era in which it was born.

The Penny Press

In the beginning, that is, before the founding of the first penny paper, the New York Sun in 1833, most daily newspapers were expensive (generally six cents each, or nearly 10 percent of the average daily wage),7 partisan, and sedate. Many included the words “advertiser,” “commercial,” or “mercantile” in their titles, reflecting their business orientation. The readership of these papers, which are variously—and often interchangeably—called the “party” or “mercantile” press, may have been high, but they had few subscribers by the standards of even a few years later.8 Before the penny era, papers were shared or read aloud to groups in the partisan clubs and inns, and sent through a partisan postal service.9

From 1830 to 1840, while the population grew less than 40 percent, the average total circulation for all U.S. dailies nearly quadrupled.10 Records for urban areas show an even more marked shift. The top-selling newspaper in 1828, Webb’s Courier and Enquirer, circulated fewer than five thousand copies a day. By 1836, fueled by his coverage of the ax-murder of the prostitute and aided by advances in printing technology, urbanization, and literacy, Bennett boasted a daily distribution of ten to fifteen thousand for his upstart paper.11 Unlike Webb’s paper, which sold for six cents a copy, the Sun, the Transcript, and Bennett’s Herald sold for a penny, hence the term “penny press.” The six-centers were sold mainly by annual subscription; the pennies were sold generally by newsboys who urgently hawked their papers in the streets and door-to-door.

The six-cent papers were connected to a tradition of party affiliation that had begun before the American Revolution; it was encouraged by the Federalists from 1789 to 1801, then by Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democrats. The post offices, printing presses, inns, and newspapers in a city or town were often connected through party affiliation and were often run by the same person. Many postmasters were also newspaper editors; through the privilege of franking, they would have “free and certain” delivery of their papers; the government, through the granting of federal printing contracts, would enjoy the expensive, yet certain, support of their editors. The Federalists increased federal postmasterships from one hundred at the start of the period to more than eight hundred by the end, helping to create what one Democrat called a “court press.” This strategy was pursued by the Democrats too; during Jackson’s 1832 reelection campaign the official Jacksonian newspaper, Francis Blair’s Globe, was franked by postmasters and congressmen to people throughout the country.12

The pennies resemble today’s newspapers more closely than the six-centers do. For one, unlike the party or mercantile press, the pennies were not supported by political parties, and the articles were more likely to cover news outside the narrow political and mercantile interests of the six-centers. Crime news, for example, was more prevalent in the pennies, as was other news, often sensationalistic, that fell beyond the six-centers’ purview. A final characteristic that separated the pennies from what came before was that they actively asserted their own nonpartisanship. The inaugural issue of the New York Transcript announced its political slant simply: “we have none.”13

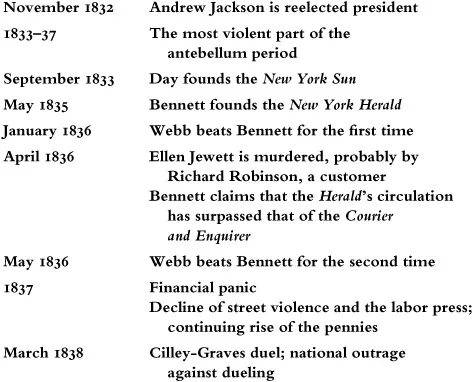

Dates of Principal Events Discussed in

This Chapter

The Press “Revolution,” “Jacksonian Democracy,” and Historians of Journalism

Journalism historians generally place the birth of modern American journalism and the rise of “objectivity” in the Jacksonian era and tie it to the “democratic spirit” of the age. What came before, they argue, was biased and primitive, the “dark ages” of American journalism. The pennies, these historians argue, brought about a democratic revolution.14 In Discovering the News, Michael Schudson advanced this view, citing the birth of universal white manhood suffrage, the “rise” of the “middle class,” and an “egalitarian market economy” as reasons. Schudson also asserted that the era saw the birth of “objectivity” claims.15 “Before the 1830s,” he wrote, “objectivity was not an issue.” He also asserted that “the idea of ‘news’ itself was invented in the Jacksonian era.” Although these claims are clearly overstated, a kernel of truth remains: many newspapers formally severed their party ties and an ethic of nonpartisanship emerged, although it was practiced unevenly.16 Unlike their six-cent ancestors, the pennies were supported by circulation and advertising, not party patronage.

That the pennies asserted their own nonpartisanship still leaves open the question of whether the papers were born out of the “democracy” of the Jacksonian age. Schudson, in Discovering the News, claimed that the modern press emerged during the 1830s, an era he titles the “Age of Egalitarianism.”17 Citing older studies of “progressive historians,” so-called because of their whiggish faith in antebellum democracy, Schudson noted that most recent histories still confirm the earlier beliefs. The revisionist view, wrote Schudson, “far from being an attack on the idea that the 1830s were an egalitarian age, confirms just that hypothesis.”18

But from the 1970s on, historians of the Jacksonian age have produced a body of work that thoroughly discredits the “progressive” view of Jacksonian democracy.19 And to suggest that revisionists, led by Edward Pessen (whom Schudson cited), confirm Jacksonian “democracy” is to misrepresent them. Pessen, for one, is unequivocal in the force of his revision: “The age may have been named after the common man but it did not belong to him.” At the end of his Jacksonian America: Society, Personality, and Politics, Pessen even suggests a new name for the period: “Not the ‘age of Jackson’ but the ‘age of materialism and opportunism, reckless speculation and erratic growth, unabashed vulgarity, surprising inequality, whether of condition, opportunity, or status, and a politic, seeming deference to the common man by the uncommon men who actually ran things.’”20

Another forceful repudiation of Schudson’s “progressive”-based view of the Jacksonian era comes from Daniel Schiller in his 1981 book, Objectivity and the News. Finding “a pattern of objectivity” emerging in a weekly newspaper that focused on crime news, Schiller devoted many pages to a discussion of the penny era and relied on post”progressive” social historians for his analysis. He believed that the pennies arose out of labor’s unrest in the late 1820s and early 1830s and saw a problem in Schudson’s theory about the “middle class,” which Schiller believed was divided into “disparate and frequently hostile” camps of merchants and artisans. The merchants’ and artisans’ work and welfare were being shaken by the rise of a national market system, Schiller suggested, but their interests were often contrabalanced. “That the penny press found a way to speak to both groups at once was its most ingenious and fundamental contribution,” wrote Schiller.21 Statements like the Sun’s “It Shines for All” reflected an appeal to the many different economic and social groups.

A New Approach to the Birth of the Commercial Press and Detachment

While historians of the Jacksonian period have become skeptical of the “democratic” promise of the age, journalism historians, with the notable exception of Schiller, have not reconciled the revisionists’ new understanding. Where Schudson sees a rising middle class, Schiller sees a group, angry and divided, but united in its opposition to the elite forces. But Schiller’s perceptive theory that the pennies appropriated labor’s class-based anger does not go far enough in understanding the turbulent storms of the age of Jackson, the race and gender wars, and the violence, both in the streets and in the newspapers, between the elite and labor, and between men of the same class. The frantic desire to make change, to move, to build, to kill, and most of all to make money is writ large in the newspaper columns of the day as well, but journalism historians have yet to capture it beyond arguing for or against Jacksonian democracy. Understanding the era is crucial to understanding what it is the pennies detached from. Webb’s violence against Bennett is a good place to start.

Bennett had worked for Webb in the pre-penny days, made a name for himself as a brash, entertaining Washington columnist, and left Webb’s charge after the Courier and Enquirer switched parties to become a Whig organ.22 Bennett, a Democrat, then tried unsuccessfully to start a Democratic paper in Philadelphia before coming to New York to found the independent Herald in May 1835. Within the year, Webb publicly beat his former employee twice on the streets of New York.

The first time Webb beat Bennett was on January 20, 1836. In his lead column on January 19, Bennett announced that it was “with heartfelt grief that we are compelled to publish the following awful disclosure of the defalcations of our former associate, Col. Webb…. But as we control an independent paper, we could not refuse it.” What follows are accounts by a broker of Webb’s failures in the stock market; as a result, he owed the broker more than $87,000. It was with “pain, regret, and almost with tears in our eyes” that Bennett published the exposé....