![]()

1

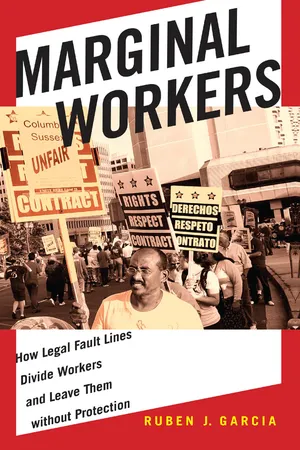

Who Are the Marginal Workers?

José Castro, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, worked in a plastics factory in south Los Angeles from May 1988 to early 1989. In fact, “José Castro” is probably not his real name, but that was the name on the birth certificate he used in order to obtain employment at Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc.1 Three years earlier, in 1986, the U.S. Congress passed an amnesty program for undocumented immigrants, and for the first time outlawed the hiring of unauthorized workers. Nevertheless, Castro found employment relatively easily, although he did have assistance from a friend who helped him fill out the paperwork to get a job with Hoffman.2 Castro was also helped by the de-unionization of the manufacturing industry in Southern California that put immigrant labor in much greater demand.3

Castro’s story would be unexceptional in many urban areas over the last 40 years had it not been for the fact that he became involved in organizing a union, resulting in an unfair labor practice case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court. After being laid off by Hoffman for supporting the United Steelworkers Union, Castro and the union sought redress from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the federal agency dedicated to protecting the right of all employees to form unions and bargain collectively. The NLRB decided to prosecute Castro’s case as a retaliatory firing in violation of the federal law protecting the right to join unions, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA).

The Hoffman case sits at the intersection of immigration and labor law. After the case worked its way through the administrative and court systems, the U.S. Supreme Court was to decide whether Castro, indisputably an “employee” within the broad definition of that term under the NLRA, nonetheless should be denied the statutory remedies because of his unauthorized immigration status. Although he was an employee owed protection under the statute (because the definition of “employee” in the NLRA does not distinguish between documented and undocumented workers), the Supreme Court held in a 5-4 decision that Castro nevertheless was not entitled to the standard NLRB remedy of back pay because granting the remedy would “unduly trench upon the federal immigration policy of preventing unauthorized employment.”4

The Court rejected the NLRB’s argument that denying back pay would actually encourage employers to hire undocumented workers because the cost of violating workers’ rights would be so low it would offset the small risk of fines being brought by the government to enforce immigration law. In 2002, for example, the federal government prosecuted only 25 criminal cases against employers for hiring undocumented workers.5 As Justice Stephen Breyer wrote in a dissenting opinion for three other justices, employers will hire illegal labor with “a wink and a nod” and then get off “scot-free” when they violate “every labor law under the sun.”6 The Court, in an opinion by the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist, replied that the employer does not get off scot-free—the employer is still subject to contempt proceedings if it engages in similar conduct again, and must post a notice to employees promising compliance with the law.7

Castro was caught in the margins of two different statutes, and his story is emblematic of marginal workers. In the chapters that follow, there are more examples of the ways in which courts have construed bodies of statutory law against the interests of workers. These cases raise a basic question about the efficacy of protective labor legislation, and whether or not a different approach to workers’ rights needs to be emphasized. I will pursue that question, and find common threads in recent efforts to put fundamental workers’ rights above the political processes of statutory change.

Here, I describe how statutory protections have failed to protect many workers besides undocumented workers, typically through judicial mis-construction. The weakness of labor law remedies for all employees has been documented in labor law scholarship.8 I recount the stories of workers whose protection is compromised by clashing statutory objectives. Castro, for example, was caught between a protective labor law statute that protects employees regardless of their immigration status, and immigration law which requires authorization to work in the United States. The fact that Castro was undocumented further marginalizes him, since undocumented workers are less likely to assert the workplace rights that they have than other workers whose immigration status is not precarious. Even though Castro asserted his rights, the operation of immigration law affected his ability to receive the same remedies as other workers.

By providing different remedies to employees who work side by side, the Hoffman decision, and many statutes, divide workers who should share common interests. The problem in Hoffman is not the statute itself, but judicial mis-construction. Some statutes, however, explicitly divide workers into different categories. Sometimes there is a good reason for divisions, such as the division between supervisors and employees in collective bargaining law, but the courts and administrative agencies have not always been correct in determining where the line between employee and supervisor is drawn.9 This divides workers who should share common interests, and makes collective change less likely.

The gaps left by statutes like the National Labor Relations Act raise questions about the effectiveness of all legislation to protect workers. Even the immigration control statute has failed to live up to its promise. Much research has shown that immigration law has not functioned in keeping with its purpose of preventing illegal employment while simultaneously meeting labor market needs for immigrant labor.10 Here, however, focuses on the dysfunction of protective labor laws for the most vulnerable workers, and how to improve the protections of those workers. I define “marginal workers” as those who are technically protected by labor and employment laws, but because of competing policy concerns or bodies of law, they lose full protection. This is especially true of more legally vulnerable workers, such as noncitizens, people of color, and women. Despite the additional protections that these workers enjoy on paper, they are often unable to fully enforce their rights. But all workers are affected by the inadequate protection given to marginal workers. In the Hoffman case discussed earlier, José Castro’s inability to organize a union affected all workers, not just those who were undocumented. These fault lines divide workers and leave them without protection.

There are a number of ways to ameliorate the situation of marginal workers. First, statutes could be modified and clarified to better protect workers. As will become evident, however, labor legislation fails to fully protect workers, and workers are generally too politically diffuse to change the law to their advantage. With regard to marginal workers, this political powerlessness is even more acute, since many of the workers discussed herein are minorities, noncitizens, or low-wage workers.

Second, courts could simply make better decisions. Many times, court decisions can be criticized as a misapplication of the law. And there have been some situations where legislatures have corrected decisions. In chapter 6, I discuss the case of Lily Ledbetter, whose case led to a Supreme Court decision and a legislative change to the Equal Pay Act. In Ledbetter’s case, the political process worked to reverse the decision, but a closer examination will reveal that the gains made by Ledbetter do not stem the tide of pay inequity in the United States.

I address a puzzling paradox about labor and employment law protections: Why are workers still poorly protected by the plethora of twentieth-century statutory innovations passed on their behalf in the last century? The reasons are many, but I focus mainly on the way in which most workplace regulation has been accomplished as the primary problem. Workplace law is seen as a political battlefield between labor and capital, with each successive political change leading the pendulum either more toward the laissez-faire or toward New Deal-style regulation. This political see-saw has created a class of “marginal workers”—workers who fall through the margins of different bodies of law that are supposed to protect them, but lack the political power to fix the holes in the legislation. These pendulum swings have produced a statutory framework that has left numerous gaps and incomplete protections for all workers.

In order to better protect marginal workers, I advocate changing the primary framework in which we conceive workers’ rights. We have tended to see workplace regulation as a contest between labor and capital—a pendulum that swings back and forth between labor-friendly and business-friendly administrations. Rather than the spoils of political victory, workers’ rights should be seen as fundamental human rights, as they are in international law. Indeed, the human rights frame is increasingly being used by scholars, unions, and practitioners to advance the cause of worker freedom. In so doing, I argue that a global constitution of worker freedom is effectively being crafted and should be encouraged through litigation and dialogue to change attitudes and behavior.

Even in the face of the Hoffman decision and the threat of deportation, undocumented workers continue to organize in unions and in litigation against their employers. Several scholars have shown the willingness of immigrants to organize in unions.11 Like other employees who have found resort to the law unavailing, undocumented workers and unions have also continued to use a dialogue of human rights for greater protection. For example, in the wake of the Hoffman decision, the AFL-CIO filed a complaint with the International Labor Organization alleging that the decision violated international human rights law. The ILO agreed, but as a matter of statutory construction of the NLRA, the Hoffman decision is still the law of the land.

The Historical Trajectory of Labor Regulation in the United States

The lack of protection in Hoffman Plastics described above raises questions about whether the worker protection goals of the progressive movement of the early twentieth century have been fully realized. In the legal realist tradition, law was an instrument for positive social change and a tool to be used with caution.12 Working hand in hand with progressive movements, legal reformers enacted workers’ compensation and state health and safety protections in the early 1900s. Then, in the 1930s, after the beginning of New Deal reforms and mass protests in the streets, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 became the first modern piece of labor legislation.

In Critical Legal Studies and other jurisprudential movements of the latter twentieth century, law was viewed with suspicion as a necessary evil for social reform. In legal realist movements, legal scholars sought to reform the law through legislative change and administrative agencies. For the early labor movement, however, law and the courts were obstacles to progress because of the labor injunction, which was used to put a stop to even peaceful picketing.13 Labor was thus more interested in solidarity actions than a resort to law.14

Still, the question of what kind of law—statutory or constitutional—confronted the labor movement in its nascent stages. Constitutional doctrine was frequently used against the labor movement in the form of “substantive due process.” Thus, the liberty interest in the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause was being used to invalidate state prohibitions of “yellow dog” contracts. These were contracts that employers required before a worker could start employment, promising that the employee would not join a union. It took the passage of the Norris LaGuardia Act of 1932 to reverse the Supreme Court’s decision in Cop-page v. Kansas to outlaw yellow dog contracts.15 In spite of this, labor activists in the early twentieth century sought to base congressional legislation to protect freedom of association and collective bargaining on the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits “slavery or involuntary servitude in the United States or any place subject to its jurisdiction.”16 Like much of the New Deal, however, labor legislation was enacted pursuant to Congress’s constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce, and survived the legal challenges of business groups that it was beyond congressional authority.17

The 1934 passage of section 7(a) of the National Industrial Act and the subsequent National Labor Relations Act in 1935 began a move toward the legal protection of concerted activity through a federal administrative agency. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) was one of the first federal agencies created for the protection of labor rights. More than 70 years after its creation, many see the NLRB as an emblem of the ossification of American labor law.18 The five-member Board that reviews the decisions of NLRB trial judges are appointed by the president. Thus, with each administration, the pendulum swings back and forth between more labor-friendly to more business-friendly decisions.

In the meantime, the protection for union organizing has diminished over the years. Studies have shown that one in 20 workers who support a union is fired for organizing campaigns at their workplaces.19 Interpretations of the NLRA by the Board and the courts have decimated worker rights.20 At the same time, there has been a proliferation of statutes to protect workers in the 75 years since the NLRA was enacted. Ironically, the proliferation of statutes has not led to a corresponding level of protection for marginal workers.

The politics of law, the title of a seminal anthology of the work of critical theorists, has not been good to workers. Critical scholars such as Alan Hyde, Karl Klare, and James Atleson have long questioned whether the law really protected workers’ interests.21 These scholars questioned the courts’ handling of labor law, but perhaps the heart of the problem lay with the statute itself—born of compromise and unable to be amended quickly.

In contemporary politics, we see this all the time. Health care legislation took years and was constantly critiqued as a choice between incrementalism or omnibus reform, until finally resulting in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010. Immigration reform similarly has proceeded at a glacial pace. The Family Medical Leave Act, while it was welcomed in 1994 for allowing workers to take off 12 weeks from work to care for sick family members, is now being criticized for not providing paid leave. It also does little to address the instances of family responsibilities discrimination that are now being brought under Title VII, often unsuccessfully, in the absence of a separate statute dealing with such discrimination. Although Congress passed the Lilly Led-better Act early in the administration of President Obama, most other business is stalled by the Senate’s filibuster rule, including some nominees to the National Labor Relations Board and Department of Labor. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision allowing corporations and unions to give unlimited funds as independent expenditures will further tilt the playing field away from ordinary workers and toward large corporations.22

The State of Workers Today

Some of the insecurity workers feel today is economic. Rea...