![]()

CHAPTER 1

Before the FLOOD, 1790–1835

In March 1829 Dr. Asabel Humphrey instructed his student to vaccinate Harriet Landon for smallpox. The physician had been hired by the town of Salisbury, Connecticut, to vaccinate its citizens. Humphrey’s student made two punctures just above Landon’s elbow joint. After the treatment Landon found that her lower arm was almost paralyzed. When her condition did not improve, she sued Humphrey for malpractice. After several witnesses, including a medical school professor, testified that the vaccination punctures were in a “very unusual place” and had caused irreparable injury, the jury awarded Landon $500 in damages. In reporting the case for the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, an editorialist “confess[ed]” that he was “somewhat incredulous as to the justice of the decision” and declared that the case should “excite the astonishment of every medical man.”1

By the mid-nineteenth century commentators in medical literature rarely expressed incredulity or astonishment when a patient sued a physician. They had begun to view the malpractice suit as a ubiquitous and possibly permanent fixture of medical practice. Before the late 1830s and early 1840s, however, malpractice cases had been rare in the United States, and physicians did not consider lawsuits a significant threat to their income or status. The social, political, legal, technological, and professional transformations that would eventually incite and sustain the malpractice phenomenon were underway, but they had not yet created the environment conducive to widespread prosecutions. The years from 1790 to 1835 were a period of relative judicial safety for the physician, and only isolated cases presaged the menace on the horizon.

“Not a Very Commendable Sight Anymore Than a Very Customary Sight”

While there is no accurate way to calculate the absolute number of malpractice suits in this or any other period, certain legal records, medical literature, and contemporary responses clearly illustrate the relative frequency or infrequency of the litigation. Soon after the American Revolution, individual compilers began publishing reports of all the cases decided in the appellate courts of the respective states.2 Appellate reports did not record cases decided at the trial level but provided state supreme court rulings on lower court judgments. Appellate decisions were accepted elaborations and, occasionally, alterations of the common law and could be used as precedents in subsequent trial and appellate court cases. Therefore, appellate decisions are valuable sources of legal theory and doctrine.

Unfortunately, they are less useful for determining the exact number of malpractice cases at the trial level. A variety of legal, social, financial, and historical factors contributed to the decision to appeal a trial court ruling, and only a small percentage of trial judgments terminated in appellate court rulings. One writer developed a formula that suggested there were nine malpractice charges filed at the trial level for each reported appellate decision. Another study estimated that the proportion was 100:1.3 The 9:1 ratio is an unreasonably low conjecture.4 The 100:1 figure corresponds with some known nineteenth- and twentieth-century rates and is probably a better estimate. For example, an 1860 Ohio medical commentator on malpractice reported that there had been over 200 malpractice cases in the state while the Ohio supreme court had reported only two appellate court decisions regarding malpractice.5 Still, the vagaries of appellate jurisprudence rob even the 100:1 figure of much of its certitude and utility.

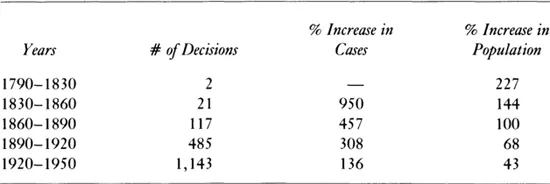

Nevertheless, reported appellate decisions serve as a broad measure of the frequency of malpractice litigation. There were 216 appellate malpractice cases reported between 1790 and 1900. Out of the 216 total, only 5 cases, or 2.3 percent, were reported before 1835.6 Despite the uncertainty involved in correlating appellate decisions to trial court judgments, the insignificant number of malpractice cases in the first third of the century contrasts sharply with the acceleration of reported decisions after 1840. Although the rate of increase intensified in the course of the nineteenth century and continued to soar in the twentieth, the initial increase in the late 1830s and early 1840s represented a fundamental break with the past. In the early part of the century malpractice suits were virtually nonexistent; after 1840 they became a prominent feature of the medical world.

The contrast between malpractice rates before and after the first third of the century is even more striking when these rates are compared to population increases. Between 1790 and 1840 the United States population grew 334 percent, from 3,929,214 to 17,069,453. During this period, the number of appellate malpractice decisions remained almost constant: 7 appellate decisions were scattered over fifty years. However, between 1840 and 1880 the population increased 194 percent, from 17,069,453 to 50,155,783, but the total number of appellate malpractice decisions jumped 1228 percent, from 7 cases as of 1840 to 93 cases by 1880.7 While the rate of appellate malpractice decisions was seemingly unaffected by a 334 percent population increase between 1790 and 1840, the rate of reported cases far outstripped population growth over the next forty years.

TABLE 18

Appellate Court Malpractice Decisions, 1790–1950

In fact, the interval between 1790 and 1840 has been the only period in American history in which the proliferation of appellate malpractice decisions failed to surpass the growth rate of the population (see table 1). These observations suggest that the increase in reported suits in the last two-thirds of the nineteenth century was not directly related to population increases, and they reinforce the conclusion that the late 1830s represented a critical turning point in the history of American medical malpractice litigation.

The low frequency of reports of malpractice in early nineteenth-century medical journals corroborates the rarity of suits before 1835. Physicians developed their views about malpractice suits in medical publications, where they communicated their attitudes to other doctors. Detailed malpractice reports helped physicians gauge the frequency of litigation, speculate on the causes of the suits, and suggest possible remedies. These commentaries, while virtually absent from early journals, were published at a furious rate beginning in the late 1830s. For example, between 1812 and 1835 the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery and its successor, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, reported on only three malpractice cases. These three cases included one suit each from France, England, and the United States.9 In contrast, between 1835 and 1865 the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal published forty-eight reports and editorials on malpractice.10 Other journals exhibited a similar disparity between the number of suits reported before and after 1840. In New York (the state considered the center of the new malpractice phenomenon in the 1840s) the medical society reported on only one malpractice incident before 1835 in its Transactions—and that involved an illegal abortion, not a lawsuit.11 Similarly, the Medical Examiner, founded in the 1830s, did not report a single malpractice case until the next decade. Publishers did not attempt to provide a comprehensive list of suits, but the scores of malpractice reports between 1835 and 1865 reflected the general trend of litigation and the level of professional concern. While these later articles were filled with the medical community’s concerns regarding the frequency of malpractice suits, the few existing reports in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal and other publications from the years 1790–1835 reflected little anxiety and treated the cases as regrettable, but isolated incidents.12

Although the field of medical jurisprudence blossomed in the early nineteenth century, legal scholars seldom, if ever, addressed the issue of malpractice before 1835.13 Two of the most widely circulated works in America were Theodoric Beck’s Elements of Medical Jurisprudence (1823) and Joseph Chitty’s A Practical Treatise on Medical Jurisprudence (1834). Neither Chitty, a lawyer, nor Beck, a New York physician, contributed a word of advice or information on malpractice.14 When R. E. Griffith added an American chapter to Michael Ryan’s work on medical jurisprudence in 1832, he merely noted that there were three types of malpractice: willful, negligent, and ignorant. He did not cite any cases or suggest that such litigation was prevalent.15 Timothy Walker, a professor of law at Cincinnati College, published an extensive First Book for Students in 1837. Walker described malpractice as the attempt to produce an abortion. He did not include the incompetent practice of physicians that resulted in permanent injuries to patients in his definition.16 When physicians and lawyers discussed malpractice in the first third of the century, they were most likely referring to nonlicensed practice, ethical violations, or criminal abortion. Civil lawsuits for damages after treatment received scant attention and generated no concern.

The Law

When late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American lawyers brought malpractice suits against physicians, they were able to refer to a slowly expanding body of legal literature for guidance, but no specialized works. Lawyers at the time of the American Revolution read William Blackstone’s or Edward Coke’s commentaries, referred to scattered English court decisions, and learned from assisting their preceptors. After Independence Americans published their own law journals, case reports, treatises, and legal handbooks.17 Despite this relative outpouring of reference material, the essential mechanics of malpractice prosecutions remained relatively unchanged.

American lawyers eagerly bought Blackstone’s Commentaries when they first became available in 1765. The first American edition printed in 1771–1772, and St. George Tucker’s annotated version published in 1803, made the commentaries accessible to virtually every lawyer in the country. In fact, for those lawyers who trained in the late 1700s and practiced into the mid-1830s Blackstone was the most important legal resource.18 Blackstone categorized mala practice not under contract or mercantile law, but under the heading of private wrongs. He defined malpractice as an injury or damage to a person’s “vigor or constitution” sustained as a result of “the neglect or unskillful management of [a] physician, surgeon, or apothecary.” Blackstone declared that malpractice was an offense because “it breaks the trust which the party placed in his physician.” The injured patient possessed a remedy for damages with the special legal action, or writ, of “trespass on the case.”19

The trespass on the case writ was the technical name of the action in a malpractice suit.20 This writ served as the common law remedy for all cases in which one person purportedly caused another an injury without the use of force. The scope of trespass on the case included damages sustained as the result of breach of duty, negligence, or carelessness. An attorney had to convince the judge and jury that the accused physician had failed to live up to the common law definition of professional responsibility and that this lapse had resulted in an injury to the defendant. Judges and lawyers drew on English precedents to form the American standard for malpractice. While the law did not demand that physicians implicitly guarantee effective treatment, it required that they exercise “ordinary diligence, care, and skill.”21 Although the precise wording of the requirement varied and was occasionally qualified in significant ways, the essential standard remained. Doctors were expected to possess and apply an ordinary and reasonable degree of care, skill, and diligence in their work with patients. Individual physicians’ performance would be measured against the therapeutic conventions, or standards of “ordinary” or average members of the profession.

The common law reserved an important role for the jury in malpractice cases. While trial judges articulated the legal standards by which juries were required to assess physicians, jurors were asked to determine “questions of fact” such as what constituted carelessness and the standards of the profession at large. Although expert medical testimony was required to guide the jury’s deliberations, laymen were entrusted with the tremendous power to designate the boundaries of acceptable medical behavior. Since juries made these decisions on a case-by-case basis, acceptable standards of care, skill, and diligence were highly sensitive to popular conceptions of the medical profession and medical practice.22 Similarly, the use of physicians as medical witnesses provided an official inlet for the personal or professional prejudices of rival medical practitioners. These provisions, contained in the common law, would play a role in the multiplication of suits in the 1840s and 1850s.

The Cases

Malpractice suits were such an uncommon occurrence before 1835 that it is difficult to draw many confident generalizations. Still, some trends do appear. The lawsuit was neither a common nor a completely acceptable response to personal misfortune. Generally, only in cases of severe injury or death did individuals overcome tradition and sue physicians. Patients and their families rarely won in court. Although malpractice suits of all kinds were infrequent before 1835, cases that did not involve death or amputation were especially rare. Fractures that did not result in amputations—which would become the most common source of suits after 1835—were seldom the source of litigation.

For example, in 1767 a physician was accused, but not charged, of malpractice when a patient died as a result of a blood-letting procedure.23 The earliest reported American appellate decision, Cross v. Guthery, was decided in 1794.24 Cross, a Connecticut physician, amputated one of Mrs. Guthery’s breasts; she died three hours later. Her husband sued the physician, asking £1,000 for “his costs and expense, and deprivation of the service and company of his wife.” Although the jury ruled in favor of Guthery, they awarded him only £40 in damages.25 In 1825, Michael O’Neil accused Dr. Gerard Bancker of infecting his four-year-old son with a fatal dose of smallpox during a vaccination and sued for $5,000. A New York City jury refused to award the father any damages.26 A third case from this period that resulted in death occurred in Ohio in the early 1830s. A physician, using a knife and hook to remove a fetus, injured the mother, who subsequently died. The patient’s husband sued the physician for malpractice, but the trial court judge dismissed the case as a nonsuit.27

In addition to cases involving deaths, patients also sued physicians in this early period when they believed that improper treatment had resulted in an amputation or a severe deformity. Another obstetric case in the first decade of the century involved a man who, having been a merchant, a grocer, a dancing instructor, and a fencing master, claimed proficiency in medicine, surgery, and midwif...