![]()

1

Introduction

Invisible Innocence

A woman who was acquitted of beating her husband to death with a baseball bat cannot be declared innocent because enough evidence pointed to her guilt, the California Supreme Court ruled unanimously Thursday.1

This headline is not an oxymoron. Jeanie Louise Adair, tried for the murder of her husband in 1999, was found “not guilty” by the jury. She then went to court to do what California law permitted: secure a formal judicial determination that she was factually innocent of the crime. The California Supreme Court refused her request because the prosecution had presented enough evidence that it would have been permissible for the jury to return a guilty verdict. Because a different jury, looking at the identical evidence, may have come to a different conclusion, she can never be declared innocent. Her status—found not guilty but not declared innocent—confronts virtually every person a jury acquits of criminal charges. Precisely because there is a gap between a verdict of not guilty and an affirmative determination that the defendant is innocent, those who administer the criminal justice system can, and typically do, treat acquittals as counterfactual. In essence, “they are all guilty” whether the state succeeded in proving it or not. As Edwin Meese, United States attorney general under President Ronald Reagan, once explained, “But the thing is, you don’t have many suspects who are innocent of a crime. That’s contradictory. If a person is innocent of crime, then he is not a suspect.”2

At first blush, the data regarding case outcomes seem to support this view both when Meese spoke and today. Only one out of every one hundred individuals formally charged with a crime will be found not guilty following a trial.3 And a not guilty verdict does not necessarily signal actual innocence. One can be acquitted for reasons unrelated to actual innocence (e.g., because the state’s evidence is shaky or a jury’s sentiment overwhelms its commitment to accuracy or the defendant is an accomplished liar), so even the one in one hundred who is acquitted is not necessarily innocent of the crime charged. Indeed, many observers suggest that it is more likely that an acquitted person is guilty than that she is innocent.4

Judges in criminal cases tell jurors that they must presume that the accused are not guilty of the crimes charged. They also tell jurors that prosecutors are obliged to introduce evidence to persuade them beyond any reasonable doubt that the defendants are guilty. If the state succeeds in doing so, then juries must convict. If the state fails to eliminate reasonable doubt about guilt, juries must acquit. A not guilty verdict says something definitive about the evidence that the state introduced: it was insufficient to eliminate all reasonable doubt about guilt from the minds of the jurors. But acquittals do not answer, nor even address, the question of whether defendants are factually innocent. All we know is that the juries were not persuaded that the defendants committed the crimes charged.

Designed to ensure that the innocent are protected to the greatest extent humanly possible, this arrangement results in what has been aptly termed adjudicatory asymmetry, the belief that guilt is based on a factual conclusion concerning the defendant’s behavior whereas an acquittal reflects only an absence of proof.5 We know (or believe we know) that the convicted are guilty of the crime because the evidence has eliminated every reasonable doubt. We do not know that the acquitted are innocent; the not guilty verdict may be a product of the government’s very high burden of proof in a criminal case or the jury’s failure to follow instructions or the failure of a key witness to testify as expected or a jury’s dislike of the law involved or a distrust of the state’s witnesses. Any of these reasons may result in reasonable doubt about guilt, and that doubt exonerates.

Because it is not an affirmative declaration of innocence, an acquittal does not preclude the state or others from showing that the defendant committed the crime in question when the test is whether the defendant’s guilt is more probable than not. For example, in one of the most famous criminal prosecutions of the last quarter-century, the jury in the criminal case acquitting O. J. Simpson of murder did not preclude a different jury finding that it was more probable than not that he did commit the murder in the civil suit when the victim’s families sought money damages.6 Nor does the acquittal necessarily preclude a judge from giving Simpson a longer sentence than would otherwise be appropriate if he is convicted of a different crime.7 Finally, should Simpson ever be charged with even more crimes, the state may be able to introduce evidence of the murders of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Goldman to demonstrate a pattern of criminal behavior. In his case, at least, prosecutors, courts, and most of the rest of us do not believe that his acquittal meant he was innocent.

Acquittals are essentially invisible. We know very little about why juries or judges conclude that defendants are not guilty. Because the vast majority of research concerning those accused of crime is based upon sentencing or prison data, we also know very little about those who are found not guilty; the acquitted have no race, gender, or social class. In practice, most prosecutors, defense counsel, and judges encounter the acquitted very infrequently. If we combine criminal cases resolved through guilty pleas and dismissals (the overwhelming majority) with the relatively few cases resolved by verdicts after trial, we find that an acquittal occurs approximately once in every one hundred cases.8 Given these statistics, it is perhaps not surprising that, with a notable exception, acquittals have remained unexamined by social scientists, legal scholars, and policymakers. Rather, they are treated as random events “signifying nothing” about the actual guilt or innocence of those prosecuted for crime.

Our collective indifference to acquittals reverberates beyond the injustice of ignoring, in a subsequent civil suit or criminal prosecution, the possibility that a jury acquittal signals innocence. If we do not know why the jury acquits, we can ignore the possibility that innocents are charged and prosecuted fully. An acquittal can be (and typically is) treated as a failure by the police, the prosecutor, the jury, or any combination of those entities to do their respective jobs appropriately rather than as the successful exoneration of the innocent. We can ignore claims that plea bargaining may force the innocent falsely to admit guilt simply to avoid the draconian penalty attached to the conviction of certain crimes. If we ignore acquittals—if we accept that “defendants are acquitted for many reasons, the least likely being innocence”9—we reduce criminal justice outcomes to extremely accurate, if sometimes harsh, convictions and very inaccurate, if sometimes emotionally understandable, acquittals. To paraphrase, convictions are from Mars, acquittals from Venus.

What We Think We Know about Acquittals

What we think we know about acquittals comes essentially from three sources: (1) a study of nearly four thousand mid-twentieth century criminal jury trials by University of Chicago law professors Harry Kalven and Han Zeisel,10 considered the seminal study of judge-jury decision making, and a handful of studies conducted to attempt to replicate its conclusions; (2) depictions of acquittals in popular culture; and (3) anecdotes. The picture is incomplete. Anecdotes and media presentations focus upon the counterintuitive: “guilty man acquitted” and “innocent man convicted” stories are more interesting than trials in which juries arrive at correct verdicts. They tell us little about the frequency or nature of trials in which the jury produced accurate results. Although Kalven and Zeisel provided an in-depth analysis of the trial judge’s explanation for the reasons why the jury acquitted when the judge would have convicted, they were not able to provide any direct information about what the people who decided the case, the jurors themselves, thought or believed. In this book, we have been able to extend our understanding of acquittals through utilizing new data gathered from jurors, judges, prosecutors, and defense counsel in four jurisdictions: the Bronx, the District of Columbia, Los Angeles, and Maricopa County, Arizona. Although these data were originally collected and analyzed by the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) in 2002 to study hung juries,11 they are a unique source of information to help us develop a more complete understanding of acquittals in the modern context.

The American Jury, published in 1966, contained an analysis of the results of a survey conducted in the mid-1950s. Kalven and Zeisel asked hundreds of judges to assess jury verdicts in terms of how the judges would have decided the cases. They found that judges agreed with the jury verdicts in 78 percent of all cases; when they disagreed, juries were far more likely to acquit when the judges would have convicted (19 percent of all cases) than they were to convict when the judges would have acquitted (3 percent of all cases). Judges and juries agreed that acquittals were appropriate in only 14 percent of all cases. Sir William Blackstone insisted, “The law holds, that it is better that ten guilty escape, than that one innocent suffer”;12 and Kalven and Zeisel’s data suggested that something like this was occurring.

Kalven and Zeisel were not content simply to report that juries were more acquittal prone than judges. They sought to explain why juries were more lenient than judges in nearly one out of five cases. Noting that a significant majority of all cases in which the juries were more lenient than the judges involved issues of both fact and values, the authors suggested that because of the existence of “evidentiary difficulty,” the juries were “liberated” to consider nonevidentiary factors—“sentiments,” in their lexicon—in resolving the questions of fact. More simply put, close cases “liberated” the juries to consider values; and this consideration frequently resulted in juries acquitting when the judges would have convicted.13 As they eloquently put it, the jury “yields to sentiment in the apparent process of resolving doubts as to evidence. The jury, therefore, is able to conduct its revolt from the law within the etiquette of resolving issues of fact.”14 Apparently, judges were immune from the influence of sentiment.

Kalven and Zeisel’s liberation hypothesis has largely guided our understanding and interpretation of jury decision making and has arguably shaped the direction and scope of social science research on juries since its publication.15 Their work, and its impact on our understanding of acquittals, is the focus of the next chapter.

The representation of trials and their outcomes in popular culture resonates with Kalven and Zeisel’s finding that juries embrace sentiment when jurors acquit those whom judges would have convicted. Courtroom scenes and trials are so common in movies, television, and literature that a majority of our experience with criminal adjudication and our expectations of it come from things we see or read as opposed to our direct experiences.16 Although the representation of trials and their outcomes in the American media is not static, little attention has been paid to the experiences of defendants who are acquitted of crimes.17 Unlike real life, where the facts are contested, in fictional accounts, the viewer or reader is generally let in on the truth through flashbacks to the events in question. Heroic lawyer characters, either defense lawyers fighting tirelessly for their (possibly) wrongfully accused clients or prosecutors upholding the values and wisdom of the state, then represent the truth that as audience members we already understand.18 Rarely do fictional judges or juries return verdicts that contradict this truth, comforting the public that through the aggressive presentation of the defense and prosecution cases, the legal process arrives at the morally, if not always legally, correct result.

Anecdotes from those who practice criminal law also tend to confirm the view that to be charged is to be factually guilty. Advocates for a zealous defense seem to delight in the irrelevance of a defendant’s potential or actual innocence to their work. As noted criminal defense attorney Alan Dershowitz asserted,

The Perry Mason image of the criminal lawyer saving his innocent client by uncovering the real culprit is television fiction; it rarely happens in real life. Almost all criminal defendants—including most of my clients—are factually guilty of the crimes they have been charged with. The criminal lawyer’s job, for the most part, is to represent the guilty, and—if possible—to get them off.19

Defense lawyer Martin Erdmann famously opined in an article in Life magazine extolling his virtues, “I have nothing to do with justice. Justice is not part of the equation.”20 Not surprisingly, prosecutors tend to agree that defense victories are counterfactual. When a jury acquitted the actor Robert Blake of murder in 2005, the district attorney for Los Angeles County informed the press that the jury was “incredibly stupid.”21

Anecdotes suggest that actual trials are lessons in civics, and acquittals are the price society pays for taking so seriously the obligation that the government has to be able to demonstrate guilt convincingly in open court. No criminal case in the past quarter-century has captured the public attention as much as the O. J. Simpson murder trial, a case in which the verdict is almost universally perceived as historically inaccurate. As one commentator characterized it, criminal adjudication is an administrative process, with trials operating as the occasional adjudicatory hearing designed to assure that the government is administering fairly.22

How Often Acquittals Occur

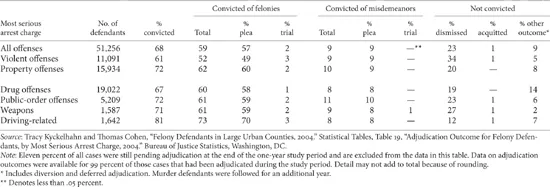

Statistics of criminal case dispositions in the largest urban counties in the United States (see table 1.1) indicate that 68 percent of the individuals charged with felony offenses were actually convicted of crimes (either felonies or misdemeanors). Of those who were convicted, the overwhelming majority (approximately 97 percent) pled guilty. Dismissals accounted for another 23 percent of the cases, acquittals but 1 percent. The remaining approximately 8 percent of cases were either disposed through alternatives to traditional criminal punishment or resolved in the following year.23 This pattern has been very consistent over time. In the last sixteen years that adjudication data have been reported by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, acquittals have consistently accounted for only 1 percent of all case outcomes.24

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics data, only 3 percent of all criminal cases were actually resolved through trials in which judges or juries rendered verdicts of guilt or innocence.25 Of the small proportion of cases that did go to trial, approximately one-third resulted in acquittals. Thus, although acquittals represented only a tiny fraction of criminal dispositions, they represented a much larger proportion of those rare cases that did go to trial.

TABLE 1.1

Adjudication Outcomes for Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties (2004)

When Acquittals Are Legally Appropriate

As a technical matter, an acquittal reflects the fact finder’s judgment that the state has failed to offer evidence sufficient to establish the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. This leaves open the possibility that the state was correct that the defendant committed the crime but simply failed to persuade twelve l...