eBook - ePub

Private Affairs

Critical Ventures in the Culture of Social Relations

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Private Affairs, Phillip Brian Harper explores the social and cultural significance of the private, proposing that, far from a universal right, privacy is limited by one's racial-and sexual-minority status. Ranging across cinema, literature, sculpture, and lived encounters-from Rodin's The Kiss to Jenny Livingston's Paris is Burning-Private Affairs demonstrates how the very concept of privacy creates personal and sociopolitical hierarchies in contemporary America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Private Affairs by Phillip Brian Harper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Private Affairs

Race, Sex, Property, and Persons

The Kiss

I begin this inquiry into the social significances of privacy in what may seem an unlikely manner, by examining some recent critical commentary on modern European painting and sculpture. Specifically, I want to consider discussions of works by Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi, and Gustav Klimt, who, for all their differences in choices of media and technique, share at least one title, which designates one or more of each one’s best-known works. I am referring, of course, to The Kiss. Each artist’s rendition of “the kiss” is, to be sure, stylistically distinctive, but as the commonality of the title suggests, all the works nonetheless develop the same theme, depicting a male and a female figure engaged in both a full embrace and the aforementioned kiss. The stylistic variation among the works has led critics to assert that each of them has a unique effect. And yet the language in which these assertions are couched suggests more congruence among the different conceptions of the kiss than is generally acknowledged in the literature. Indeed, it would seem that one particular formulation of the kiss’s cultural significance has achieved such hegemony as to make it ripe for the interrogation that I want to pursue here.

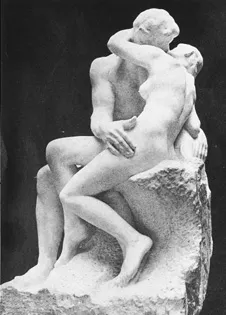

Let us consider, for example, Bernard Champigneulle’s description of Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss (1886) as “that luminous symbol of love and of the twofold tenderness of man the protector and woman stirred to the depths of her being.”1 What is, perhaps, most familiar in this assessment is the positing of the male figure as imperturbably stolid (in his protectiveness) even as he acts upon the female in such a way that she, by contrast, is utterly moved. The degree to which this particular conception of heterosexual communion has been thoroughly stereotyped is best indicated by its pervasiveness in both soft-and hard-core pornography, in which the pleasure that is supposed to characterize the sexual encounter is generally registered through the woman’s groans and facial expressions while the man, despite his customary energy and athleticism, appears comparatively unaffected. Notably, Champigneulle does not actually identify the characteristics of the sculpture that indicate to him the subjects’ emotional states (and, frankly, I cannot discern them myself); instead, his claim acquires its plausibility through its recourse to representational conventions of the heterosexual relation with which we are extensively familiar.

At the same time that he notes the different moods of the two figures, however, Champigneulle also comments on their formal continuity with one another; “[f]rom lips to feet,” he remarks, “both figures are pervaded by the same fluidity” (157). It is in the interplay between this continuity, on the one hand, and the distinction of masculine and feminine sensibilities, on the other, that we can identify the basis for the characteristic conception of the heterosexual coupling as the necessary overcoming of a fundamental difference between the genders—a conception that is reflected in much of the critical commentary on Rodin’s sculpture. For instance, having noted the “incredulous” critical reaction to the stolid “reticence” of The Kiss’s male figure, Albert E. Elsen goes on to suggest that that incredulity might be quelled by the sculptural “fusion” of male and female that Rodin elsewhere achieves, thereby clearly indicating the degree to which such fusion is considered “natural” to the heterosexual encounter—construed as a convergence of polarities—whose teleological imperative of union is represented in the kiss itself.2

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1886.

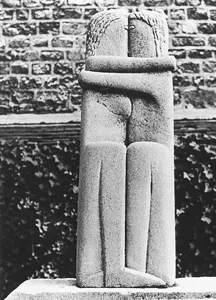

This postulation of the heterosexual kiss’s significance as the overcoming of gendered difference also marks commentary on the work of the Romanian-born French sculptor Constantin Brancusi. Brancusi completed numerous versions of his own Kiss, most in stone, and according to Sidney Geist, all of these represent “the antithesis of The Kiss of Rodin” in their frank abstractionism.3 Nevertheless, Geist’s analysis implicates Brancusi’s work in the same conception of the kiss’s import that informs Champigneulle’s commentary on Rodin. Geist begins his examination of one of Brancusi’s earliest versions of the work, from about 1907–1908, by noting that the “two lovers … are eye to eye, their lips mingle, the breasts of the woman encroach gently on the form of the man” (28). He goes on to stress the merged quality of the two figures—“[t]he unity of the bodies”—but finds fault with their arms, whose “round, ropelike separable character … violates the continuity of the stony matter” (28, emphasis in original). This violation is repaired, according to Geist, in a more columnar version of The Kiss done in 1909, which presents the two figures with full bodies, “the legs of the woman embrac[ing] those of the man” (36). This Kiss, Geist claims, “accomplishes the weaving of forms without destroying the integrity of the stone”; and by thus manifesting such formal continuity the later work, Geist asserts, “marks an advance … over the first Kiss” (36). We are, it seems, meant to apprehend the extent of that advance from Geist’s assessment that Brancusi’s “image of two figures locked in an embrace is a permanent expression of the unity of love, which Plato called ‘the desire and pursuit of the whole’” (37).

Constantin Brancusi, The Kiss, 1907–8 (Craiova). Copyright © 1999 ARS, New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Constantin Brancusi, The Kiss, 1909 (Montparnasse Cemetery). Copyright © 1999 ARS, New York/ADAGP, Paris.

In the conjunction of Geist’s privileging of the “pursuit of the whole” that is evidently figured in the heterosexual union, and his enthusiasm for Brancusi’s abstractionist aesthetic (which is discernible throughout his essay), we can identify a dichotomy similar to that which characterizes the Rodin criticism: formal continuity set against emotional distance. Moreover, in his anxiety to render this schema in clearly heterosexual terms, Geist actually seems to betray his own modernist ethic by insisting that The Kiss’s representation of heterosexual union is based not only in realism but, further, in biography. In his assessment of the earlier Kiss, Geist notes the peculiarities of the two different figures in the sculpture:

The man’s hair falls over his brow, much as Brancusi wore [his] in 1904. The line of the hair starts at a higher point on the woman, giving her a somewhat longer face than the man, and making her appear slightly taller (and Brancusi was short). It is reasonable to speculate that this carving … celebrates a consummated kiss. If it does, we must conclude that what seems to be a set of formal variations has a biographical origin. (29)

And, in his commentary on what is arguably Brancusi’s best-known version of The Kiss, done in 1912, Geist implicitly faults the sculpture for “los[ing] the immediacy of the earlier versions as it moves toward pure design” (40). Thus Geist’s celebration of Brancusi’s modernist aesthetic, which he prizes for its “timelessness, simplicity and autonomy” (28), is mitigated by his uneasy desire to assimilate the sculpture to a narrative of recognizably heterosexual love in which the kiss must be the inevitable “consummation.” Indeed, when the work is so abstract as to present figures that are barely differentiated, even, let alone gendered—thus rendering impossible this sort of heterosexual recuperation—Geist is forced to desperate measures. Considering the presentation of the kiss in Medallion, from around 1919, Geist negotiates the potential for distress that is implicated in the figures’ unisexual appearance by construing those figures as not human but, rather, immortal. This version of the work, he says, “echoes Donne: ‘Difference of sex no more we knew than our guardian angels do’” (80–81); he thus casts the carving’s lack of gender differentiation in terms of angelic purity rather than human decadence.

Constantin Brancusi, The Kiss, 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). Copyright © 1999 ARS, New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Constantin Brancusi, Medallion, c. 1919 (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris). Copyright © 1999 ARS, New York/ADAGP, Paris.

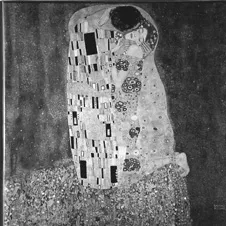

While Geist may appear singularly ingenious in his management of the more troubling aspects of Brancusi’s various Kisses, however, so potent and versatile is the mythology of heterosexual love that the dichotomous impulse it animates in Geist’s consideration of Brancusi’s work might be incorporated into a completely different interpretational scheme without in the least forfeiting its ultimate significance. In his study of the work of Austrian artist Gustav Klimt, Frank Whitford notes the contemporaneity of Brancusi’s sculpture and Klimt’s famous painting The Kiss (1908), claiming that

to compare them is to see instantly the differences between Klimt’s work and that of another, more completely modern artist.… [W]hereas Brancusi simplifies, reduces and rarefies, Klimt complicates, allows his ornament to proliferate and adds layer after layer of effect and allusion.4(118)

In short, as a less “modern” artist, Klimt is less abstract in his work than Brancusi, and thus Klimt’s painting needs less to be reclaimed by a realistic narrative of heterosexual love than it needs, on the contrary, to be rescued from an overly specific interpretation derived from autobiographical realism. Consequently, while Geist underscores the extent to which Brancusi’s Kiss can be traced to the artist’s own experiences and thus presumably reinvested with the heterosexual significance that it is always threatening to lose through its high abstraction, Whitford denies the biographical significance of Klimt’s painting (the heterosexual meaning of which is relatively clear) in order to claim that the work registers the “universality” of the love it apparently treats:

In some of the preliminary drawings the man is depicted with a beard and it has therefore inevitably been suggested that the male figure is Klimt himself and the woman an idealized portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, whose affair with Klimt was supposedly continuing when The Kiss was painted. The only evidence for this, however, is the awkward position of the woman’s right hand [Adele Bloch-Bauer had an anomalously configured right hand] (but this masks the fourth, and not the disfigured middle finger). The painting is not autobiographical but a symbolic, universalized statement about sexual love. (118)

What Whitford takes as “universal” about the depiction, it would seem, is the notion (which the painting apparently espouses) that the kiss represents the logical end of the heterosexual encounter—a notion explicitly evidenced in the title of a forerunner to The Kiss, Klimt’s Fulfillment (1905–9), which depicts a scene very similar to that presented in the later work. (One notable difference, according to Whitford, is that in The Kiss, “the woman’s ecstasy … [is] revealed in her face” (117), just as I have suggested is usual in representations of heterosexual erotic pairing.) It is necessary, I think, to examine critically this very notion, for if we view the kiss merely as emblematizing the consummation of heterosexual love, we miss its import in other social contexts; at the same time, it is necessary to recognize the extent to which that consummation is taken to be the primary significance of the kiss before we can fully appreciate its meaning in the other economies of signification that I want to consider here.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1908 (Oesterreichische Galerie, Vienna). Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

If, as I have suggested is indicated in the art criticism discussed above, the kiss is generally understood to signify the logical consummation of the heterosexual encounter, then, conversely, any relationship between a man and a woman that registers as “heterosexual” must be considered as founded on an erotic charge that is “hidden” beneath the relationship’s day-to-day aspect, and that achieves public expression in the kiss. The kiss, then, in teleologically “fulfilling” that relationship, retroactively invests with an inevitably erotic significance all the interactions that have heretofore constituted the relationship. Further, because the notion that the sexualized encounter does ineluctably comprise such a telos is so strong a force in Western culture, we are able to “know” that any recognizably heterosexual relation “really” represents an erotic engagement, however “innocent” of eroticism the constituent interactions in that relation may appear to be. The status of the properly heterosexual relation, then, is always that of the “open secret,” the revelation of which (through the publicized kiss, for example) will startle us only because, as D. A. Miller has pointed out, “[w]e too inevitably surrender our privileged position as readers to whom all secrets are open by ‘forgetting’ our knowledge for the pleasures of suspense and surprise.”5 Miller invokes “readers” because he is discussing specifically our experience of novelistic narrative. Yet “reading” seems an apt description of our activity as decoders of social texts as well as fictional ones. After all, as Miller indicates, “the social function of secrecy [is] isomorphic with its novelistic function,” and that function is “not to conceal knowledge, so much as to conceal the knowledge of the knowledge” (206). The necessity for this concealment, in Miller’s assessment, derives from a subject’s desire to disavow the degree to which he or she has been absorbed and accounted for in the social totality he or she inhabits. That is to say that secrecy serves as a sort of “defense mechanism” by which, as Miller puts it,

Gustav Klimt, Fulfillment, detail of the Beethoven Frieze, 1905–9 (Oesterreichische Galerie, Vienna). Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

the subject is allowed to conceive of himself as a resistance: a friction in the smooth functioning of the social order.… [It is] the subjective practice in which the oppositions of private/public, inside/outside, subject/object are established, and the sanctity of their first term kept...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Sexual Cultures

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Private Affairs: Race, Sex, Property, and Persons

- 2 “The Subversive Edge”: Paris Is Burning, Social Critique, and the Limits of Subjective Agency

- 3 Playing in the Dark: Privacy, Public Sex, and the Erotics of the Cinema Venue

- 4 Gay Male Identities, Personal Privacy, and Relations of: Public Exchange: Notes on Directions for Queer Critique

- 5 “Take Me Home”: Location, Identity, Transnational Exchange

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author