![]()

1

The Causes of Corporate Crime

An Economic Perspective

CINDY R. ALEXANDER AND MARK A. COHEN

This chapter examines the causes of corporate misconduct from an economic perspective, focusing on crime. Our purpose is to provide an understanding of why corporate misconduct occurs and to identify some considerations that are important to enforcement authorities and corporate monitors in determining how best to deter it. These considerations have grown in importance over the past decade, especially with the emergence of governance reform and the related use of DPAs as means for promoting monitoring and related deterrence of crime in business organizations.1

The threat of sanction is central to the deterrence of corporate crime in this setting. This includes the chance of getting caught and the penalty that the offender expects to pay, if caught. Two features of crimes by corporations are key. First, crimes tend to be committed by multiple individuals, not just by one individual acting alone. Second, individuals are linked within corporations through what some economists have termed a “nexus of contracts.”2 This means that individual choices in the corporation are linked in a predictable manner, depending on the firm’s structure and governance. The actions of individuals who would never think of committing a crime can influence the actions of those who are more prone to misconduct. The possibility of deterring crime by penalizing—or holding accountable—an individual who does not directly engage in crime is thus apparent; blaming the top management for inadequate internal controls or a corporate culture that fosters crime can be an effective response to corporate crime in some instances, even when the top management had no direct role in the offense. Similarly, holding shareholders accountable (via the corporate entity) can be an effective means of deterrence in settings where the corporation is generally responsive to the interests of its shareholders, the enforcement authority faces difficulty in identifying the guilty employee (or the guilty employee is judgment proof), and the shareholders are not themselves an injured party in the misconduct.

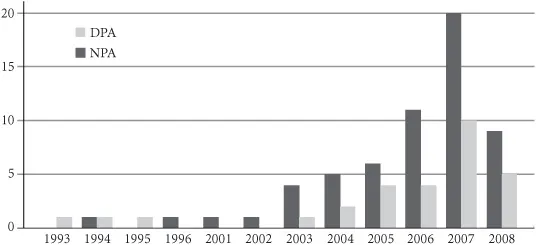

FIGURE 1.1

Publicly Announced DPAs and NPAs, by Year (estimated)

Reforms to governance at the top of the corporation have thus emerged as a potentially effective substitute for higher monetary sanctions in deterring corporate crime. This can be seen in the past decade’s reforms under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and in the increased use of prosecution agreements, notably DPAs and NPAs (see Figure 1.1).3

The framework of this Chapter applies across the wide array of offenses for which corporations may be held accountable, including violations of health, safety, or environmental regulations; antitrust conspiracies; bribery and corruption on government contracts; and securities fraud. In the United States, those legally responsible for corporate crime can be as varied as the hourly employee who illegally dumps a barrel of hazardous waste, the manager who conspires with competitors to rig bids on a local road-building project, or the senior executive who fails to put effective controls in place to ensure that foreign government officials are not bribed to obtain a contract or that the firm’s financial reporting practices meet the needs of investors.

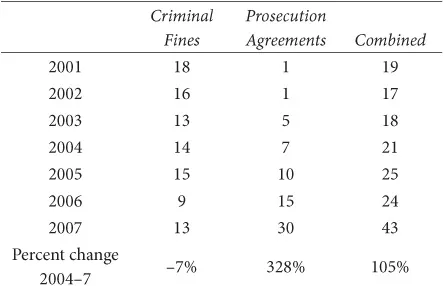

The pattern of increased reliance on prosecution agreements is apparent even when compared with the use of traditional criminal sanctions around the peak period of their use, during 2004–2007. While there has been only a slight decrease in the number of traditional criminal prosecutions resulting in fines of more than $1 million, the number of companies without criminal prosecution but having fines of more than $1 million and a prosecution agreement increased dramatically from as few as seven in 2004 to as many as thirty in 2007. Combined, the number of companies receiving $1 million or more in sanctions doubled, with the number in 2007 being 105 percent higher than in 2004. Our evidence is that more than three-quarters of the prosecution agreements were accompanied by monetary sanctions of more than $1 million in this period. The early experience is that prosecution agreements may be a less costly means of delivering monetary sanctions than traditional channels of criminal enforcement. Since the two can deliver sanctions for similar conduct, they can be thought of as substitute means of promoting deterrence—with prosecutors being able to increase use of the lower-cost substitute while only slightly decreasing the use of the higher-cost substitute and thus producing a greater number of enforcement actions overall. The evidence from the table is consistent with this; prosecutors appear not to have reduced substantially their criminal prosecution rate in exchange for prosecution agreements; instead, they appear to be increasing the overall number of enforcement actions.

Looking forward, the creation of institutions to promote greater diligence within organizations may be seen as a substitute for higher criminal sanctions in promoting general deterrence. That is, efforts to increase the probability of detection and related sanctions—even if undertaken by parties within the corporation—can be an effective substitute for higher criminal penalties or more stringent government monitoring in the prevention of crime. One strategy is to identify more clearly who within the corporation will be held accountable for a crime prior to its occurrence. The effect is to increase the ex ante probability of sanction among those individuals (at the expense of reducing the probability of sanction among other individuals), thereby concentrating the incentive to prevent the crime among those individuals. The challenge lies in distinguishing the individuals in the organization who are best equipped to prevent the misconduct (i.e., lowest-cost avoiders), either directly (by not undertaking it in the first place) or indirectly (by taking steps to improve governance or by blowing the whistle against ongoing misconduct).

TABLE 1.1

Growth in use of prosecution agreements relative to criminal fines against corporations: cases resolved with monetary sanctions above $1 million, by year

Although the focus of this chapter is on corporate crime, the underlying behavior we are interested in is organizational “misconduct” that can include administrative or regulatory violations, consumer fraud, securities fraud, or any activity taken by (or on behalf of) an organization that is subject to criminal or other legal sanctions. Whether misconduct is deemed criminal in the U.S. system depends on the independent choices of a judge and prosecutor. The prosecutor’s decision to bring criminal charges against an alleged corporate wrongdoer may indeed depend upon many factors—such as the strength of evidence, solvency of the corporation, and prosecutorial priorities. It also depends on the availability of substitute forms of sanction, such as may occur through the use of prosecution agreements. For some offenses, it can thus be difficult to determine at the outset whether a criminal or noncriminal sanction (or both) will apply in the event of detection. Thus, while we are primarily interested in crime, theories of the causes of corporate crime necessarily encompass corporate misconduct more generally.4

Section I of this chapter will review the fundamental insights of the economic model of crime and its origins, beginning with a review of the basic economic model and the empirical evidence on its practical relevance. Section II examines implications for the choice of enforcement strategy and design of sanction. Section III briefly recaps the empirical literature on corporate criminal sanctions. Section IV provides a discussion of practical implications for the design of enforcement institutions, followed by a brief conclusion.

I. Why Do Corporations Commit Crimes?

The reasons for corporate crime are numerous and implicate many changing factors. In this section, we examine the causes through the lens of an economic model in which corporate crime is the outcome of decisions by rational utility-maximizing individuals who have the ability to incur criminal liability on behalf of the corporation.5 Within this rational-choice “deterrence” framework, individuals weigh the costs and benefits of crime-related activity against the expected sanction to maximize their private utility under the constraints of the organization in which they find themselves (or select into). The underlying economic theory of why individuals commit or are deterred from crime is generally attributed to Becker, although the roots can be traced back to classical criminology (e.g., Beccaria and Bentham).6 This model has both practical and nonnormative applications. Focusing here on a nonnormative analysis allows us to predict when the crime rate is likely to go up or down, and in which companies we are more or less likely to see criminal activity. We begin with the simplest case of the individual acting on behalf of the organization.

Individuals Acting on Behalf of a Corporation

Although corporations can be seen as collections of individuals organized around a series of implicit and explicit contracts, corporate misconduct is often traceable to the choices of specific individuals. Those individuals are then said to have “caused” the criminal activity or been “negligent” in allowing activities that led to corporate criminal violations. Whether explicitly sanctioned or prohibited by their organizations, individuals are legally assumed to be acting on behalf of their employer in these situations. Of course there are various decision makers within any organization, including owners, managers, and employees. While their motivations might be similar—for example, monetary income, leisure time/quality of life, reputation within their community—individuals in corporations will vary in their opportunities, and hence face different private payoffs from committing crimes.

Not all corporate crimes require individual (or corporate) intent; some strict liability offenses carry criminal sanctions, for example, and corporations can face vicarious liability. Nevertheless, it is often possible to consider these strict liability crimes as being the outcome of decisions on the part of individuals. For example, an “accidental” rupture of a chemical tank might be linked to an individual decision maker who chose an inadequate level of prevention. Thus, the individual’s action becomes a “causal factor” in the strict liability crime, but not necessarily the only factor. In many cases, a series of inactions (as opposed to identifiable actions) might have contributed to the outcome. For example, top management decisions might have determined the incentives and rewards for plant-level employees’ actions that contributed to midlevel managers’ budgeting decisions. Midlevel managers might have chosen not only how much to spend on maintenance but also how much of their time to devote to monitoring those employee actions. Lower-level employees might have decided how to allocate the time spent on maintenance, and so forth. In combination, these decisions can have an impact on the overall probability of a chemical spill—even if it would legally be difficult to directly tie the individual decisions and related behavior to a spill.

Why do some people commit corporate crimes while others do not? In the economic model of crime, rational individuals weigh their expected private gain from committing a crime against their cost. The expected costs of committing a crime include the cost of executing the crime itself and other costs that depend on the probability of detection—such as formal court-ordered sanctions, informal sanctions (loss of future business), and “psychic” costs to the individual (lack of self-respect, loss of standing in the community, etc.). The expected private gain from an individual’s participation in corporate crime can include increased income, more leisure time, higher status within the organization, and so forth. Thus, corporate crime is the result of individual decisions made in the face of various opportunities and constraints.

The propensities of individuals to commit crime can be difficult for a corporation to control. Some people have greater moral inhibitions than others; some are extremely averse to going to jail while others are less concerned about the consequences of such punishment. Similarly, individuals will vary according to their job status, economic situation, stature within the community, and so forth. Individuals with little stature in the community may feel they have little to lose if caught committing a crime, whereas those of extremely high stature in the community may feel they have a lot to lose and thus perceive a higher private cost from committing a crime.

The opportunity to engage in crime can be easier for the corporation to control. Some corporations may be able to eliminate the opportunity from their business environments altogether. The capacity to influence the risk of crime will vary by firm, industry, and the characteristics of managers. Potentially, every transaction within a firm carries the opportunity to act criminally. For instance, every sale carries with it the opportunity to illegally misrepresent the quality of the product or service to the customer. Every accounting entry may be accurate or fraudulent, day-to-day production may meet or violate emission standards, and so forth.

Opportunities to commit crime vary not just in the ease of committing the crime but also in the detection risk they present. For example, it may be easier to violate emissions standards for one day and avoid a random emissions audit than it is to set up a price-fixing conspiracy and risk that one of the potential coconspirators will report the conspiracy to the Department of Justice (“DOJ”).

Corporation as the “Decision Maker”

Instead of focusing on individual actions, we can consider crime as the outcome of company-level decisions. A firm that is maximizing expected profits essentially weighs its expected sanction against the expected private gain from the crime. The expected sanction depends, as before, on the probability and severity of c...