eBook - ePub

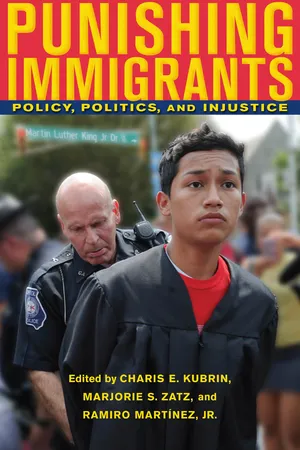

Punishing Immigrants

Policy, Politics, and Injustice

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Punishing Immigrants

Policy, Politics, and Injustice

About this book

Arizona's controversial new immigration bill is just the latest of many steps in the new criminalization of immigrants. While many cite the presumed criminality of illegal aliens as an excuse for ever-harsher immigration policies, it has in fact been well-established that immigrants commit less crime, and in particular less violent crime, than the native-born and that their presence in communities is not associated with higher crime rates. Punishing Immigrants moves beyond debunking the presumed crime and immigration linkage, broadening the focus to encompass issues relevant to law and society, immigration and refugee policy, and victimization, as well as crime. The original essays in this volume uncover and identify the unanticipated and hidden consequences of immigration policies and practices here and abroad at a time when immigration to the U.S. is near an all-time high. Ultimately, Punishing Immigrants illuminates the nuanced and layered realities of immigrants' lives, describing the varying complexities surrounding immigration, crime, law, and victimization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Punishing Immigrants by Charis E. Kubrin,Marjorie S. Zatz,Ramiro Martínez, Charis E. Kubrin, Marjorie S. Zatz, Ramiro Martínez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Immigration Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Most scholarly research on immigration and crime has focused on a subset of questions: Are immigrants more crime-prone? Do areas where immigrants reside experience higher crime rates? What are the larger connections between immigration and crime in the United States and abroad? For the most part, these questions have been satisfactorily addressed. Contrary to public opinion, it is now well-established in the scholarly literature that, in fact, immigrants commit less crime, particularly less violent crime, than the native-born and that their presence in communities is not associated with higher crime rates. Consequently, scholars are eager to move beyond the question: “Does a connection exist?”

This edited volume does just that by broadening the focus to encompass issues relevant to law and society, immigration and refugee policy, and victimization, as well as crime. There has been relatively little research on victimization among immigrants, and even fewer studies analyze legal issues of concern to immigrants and the communities in which they reside. Clearly, though, the three are interdependent and researchers must begin to consider how each intersects with the others to shape immigrants’ experiences and realities.

Within the larger context of immigration and crime, law, and victimization, the edited volume focuses on two critical areas: First, chapters uncover and identify the unanticipated and hidden consequences of immigration policies and practices here and abroad at a time when immigration to the United States is near an all-time high. In the United States, these collateral consequences include harms to individuals (e.g., victimization by unscrupulous employers, human traffickers, etc.) and to communities (a result of reduced crime reporting, reduced efficacy of public health and school systems, etc., when immigrants are fearful of interacting with public institutions and authorities). In other contexts, these state-created vulnerabilities may include, for example, forced relocations and displacement, rape and other assaults, and ethnic cleansing. We expand the analysis to also consider the ramifications of deportation for individuals who grew up in the United States but who are forcibly removed and must adapt to new laws and social norms in a nation of origin which is not “home” to them.

Second, chapters in this volume illuminate the nuanced and layered realities of immigrants’ lives and describe the varying complexities surrounding immigration and crime, law, and victimization. These nuanced realities and complexities include, most especially, the racialized and gendered overlays. For example, many state-created vulnerabilities have patterned outcomes, with some immigrants particularly vulnerable to victimization as well as deportation (e.g., women may be at greater risk of intimate partner violence and less able to protect themselves when their immigration status is tied to that of their husband; immigrants from some countries can claim refugee status more readily than others; linguistic and cultural differences make some groups more readily identifiable as immigrants than others; day laborers may experience special vulnerabilities, and so on). Moreover, immigrant status may intersect with schooling, labor market, and other institutional structures to differentially affect employment opportunities and these patterns may, in turn, vary across nations and regions.

We situate these themes—the hidden consequences of immigration policies and practices and the nuanced and layered realities of immigrants’ lives—within the larger context of immigration and social control, particularly new modes of control in a post-9/11 era.

In essence, this edited volume focuses on the hidden consequences, nuanced realities, and complexities that emerge when we delve beyond the immigration-crime nexus to consider multiple forms of victimization, the impacts of socio-legal policies and practices on communities, and the responses of individual immigrants and immigrant communities to their victimization. Throughout, the chapters interweave U.S. and global patterns, concerns, and reactions to the movement of people and labor across borders. Equally important, they do so from explicitly interdisciplinary perspectives, with contributions from scholars, politicians, and practitioners trained in anthropology, criminology, geography, law, political science, social work, and sociology. By drawing on multiple locations and cross-cutting themes, the collection expands our understanding of the multifaceted, complex linkages among immigration policy, crime, law, and victimization, and points legal and social science research on immigration in these new directions.

Change and Continuity in Immigrant Flows

Worldwide, close to 190 million people, representing 3 percent of the world’s population, lived outside their country of origin in 2005. The United States and Western Europe have seen the greatest increases of immigrant and refugee flows, with marked increases also evident in Canada, Australia, and Russia, among other sites. In contrast, emigration has been greatest from Mexico, Central America, China, India, and parts of Africa, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia (New York Times 2007). While much of the migration flow reflects the movement of labor, as individuals and families seek better employment opportunities, the movement of political refugees is also an important and growing component. In 2007, 338,000 new asylum applications were made in European and non-European industrialized nations. Half of the asylum-seekers were from Asia, and another 21 percent from Africa. The United States, France, and the United Kingdom received the greatest share of asylum requests, with significant numbers also appealing to Sweden, Canada, Germany, Australia, and New Zealand (UNHCR 2008).

Considering just the United States, the Pew Hispanic Center estimates that roughly 12 percent of the U.S. population in 2010, or 40 million persons, were born outside of its borders (Passel and Cohn 2011). Of these, most are naturalized citizens or legal permanent residents, students and temporary workers on temporary visas, and refugees, with about 28 percent estimated to be undocumented (2011: 10). About half of the undocumented residents (58 percent) are from Mexico and another 23 percent are from other Latin American countries, with one-fifth (18 percent) coming to the United States from other parts of the world (Passel and Cohn 2011).

These statistics remind us that the stream of immigrants currently reshaping the United States, unlike at the turn of the last century, is no longer primarily of European origin. The racial/ethnic/immigrant composition of many communities and cities has grown increasingly diverse, and while most newcomers are from Latin America, others are born in Asian and European countries. Still, the U.S.-Mexican border has supplanted Ellis Island as the most prominent entry point into the nation, and many politicians and pundits are concerned about the potential of chaos and disruption in border communities (Rodríguez, Saenz, and Menjívar 2008). This concern is linked, in part, to the burgeoning Latino (Hispanic) population in the United States and projections that these numbers will continue to grow (ibid.). While Latinos and Asians are still concentrated in the west and southwest, immigrants also have settled in other regions of the country and are working in diverse sectors of the economy. Newcomers are now moving into cities with older immigrant populations that have long served as traditional settlement points in the northeast and midwest regions. Others have moved into rural areas where few immigrants historically resided, contributing to residents’ concerns about their growth, hardening residents’ attitudes toward the newcomers, and generating angst over the perceived political, economic, and criminal threat of Latino and other immigrants.

Immigrant growth, legality aside, has implications for the nation. Stereotypes regarding newcomers dominate public discourse in the United States and paint immigrants as dangerous threats to the nation (Chavez 2008; Nevins 2002; Ngai 2005). Immigration policy now reflects, in part, local concerns about economic competition, racialized political threat, and fear of crime, even in the absence of systematic evidence revealing a connection between immigration and crime (Johnson 2007; Martínez and Valenzuela 2006; Newton 2008). Moreover, policy mandates for controlling the American border and “illegals,” who are primarily of Mexican origin, are encouraged by politicians and commentators for the sake of enhancing “national security” and preventing crime. Such mandates include demanding proof of citizenship, deploying the National Guard, building a fence on the border between Mexico and the United States, encouraging the growth of self-styled “militias,” and labeling “undocumented” immigrants as criminal aliens (Doty 2009). Taking this one step further based on arguments that the federal government is not doing enough to curb immigration, states and local governments across the country are enacting laws and approving ballot referendums designed to “get tough” on immigration. Most notably, in April 2010, the governor of Arizona signed into law Senate Bill 1070, which makes it a crime to be undocumented and threatens law enforcement officials perceived to be lax in enforcing immigration law with lawsuits.

New Modes of Social Control

These numerous and varied immigration policies, we argue, constitute new and expanding modes of social control in the United States. The first set of chapters in this volume outlines new modes of control by discussing recent laws and policies designed to control immigrants and immigration more generally. What emerges from this collection of policies and practices, as described in the chapters, is a nationwide re-visioning of immigration enforcement driven by federal law and policy, as well as by politics at the local level. These enhanced control strategies, as we come to find out, are not unique to the United States but can be found elsewhere, including in Europe and Australia.

In the first chapter of this section, Panic, Risk, Control: Conceptualizing Threats in a Post-9/11 Society, Michael Welch argues that part of the recent concern over immigrants is linked to fear of terrorism, which rose after the attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 and, later, on 9/11. States like Florida, Texas, and California denied basic education, health, and social services to immigrants—actions that were eventually seen as the first step in controlling newcomers. Further steps have included giving federal agencies “unprecedented authority” to target immigrants and deport newcomers under the guise that they constituted threats to national security. The chapter by Welch contributes to our understanding of the overlap of criminal and administrative laws post-9/11 and documents how subsequent attempts to control immigration have contributed to the growth of an industry benefiting from the overlapping wars on crime, “illegal” immigration and, of course, terrorism. Drawing from literature on moral panics and risk societies, Welch demonstrates how our thinking about immigration and terrorism has escalated from panic to a more permanent state of feeling at risk, thus making concern about growth of immigration and the need for enhanced control more understandable in the larger context of the potent social and political forces shaping control strategies. Welch compares trends in the United States with trends in Australia, providing a comparative approach for understanding linkages among panic, risk, and control of immigrant populations.

Within the United States, concern about the growth in immigration has also led to legislation flourishing at the city, county, and state levels, measures which are viewed by many as anti-Latino or anti-immigrant. Yet research on the possible mechanisms that give rise to such sentiment across collectivities is underdeveloped. Moreover, little is known about the ways in which social processes contribute to this sentiment or anti-immigrant reactions. In their chapter, Growing Tensions between Civic Membership and Enforcement in the Devolution of Immigration Control, Doris Marie Provine, Monica Varsanyi, Paul Lewis, and Scott Decker address these issues, focusing specifically on Latinos. They first remind us that while much of the Latino growth has been in traditional settlement areas in the southwestern United States, there is substantial movement to places that are new destinations or where few Latinos resided in previous decades (Rodríguez et al. 2008). The emergence of anti-immigrant laws or ordinances has proliferated in these new destination points. They have been aimed at preventing “illegals” from securing housing, punishing business owners for employing the undocumented, and allowing local police to search for “illegals” or ask about legality status, the latter historically left for the federal domain (Varsanyi 2010). Many communities now encourage local police to engage in federal immigration activities and enforce immigration laws through the investigation, apprehension, and detention of undocumented immigrants, part of what is known as the 287(g) program, a clause in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (Khashul 2009). This agreement also allows local police officers to use federal databases to check the immigration status of individuals and to process them for deportation hearings when necessary.

Most police departments and local governments have not rushed to assume federal responsibility, but some are actively enforcing immigrant-status violations (see Decker et al. 2009) including policing internal immigration enforcement through the so-called Secure Communities initiatives, as discussed by Provine and her colleagues in their chapter. Other draconian anti-immigrant initiatives are apparent in new destination points such as Hazleton, Pennsylvania. According to the 2000 Census, Hazleton had about 23,000 residents, 5 percent of whom were Latino. In 2006, local officials passed the Illegal Immigration Relief Act, a measure that would have resulted in racial profiling, discrimination, and denial of benefits to legal immigrants. This ordinance imposed fines of up to $1,000 to landlords who rented to “illegal” immigrants, denied business permits to corporations who employed undocumented immigrants, and made English the official language of the village (Rodríguez et al. 2008). The consequences of anti-immigrant/Latino initiatives are that all immigrants and Latinos are singled out by politicians, the media, and authorities and, thus, presumed illegal (ibid.).

If this is going to happen anywhere, perhaps it is most likely to occur in states such as Arizona, which have enacted some of the harshest anti-immigration laws on the books. Consider Senate Bill 1070, mentioned earlier, which makes it a crime to be undocumented and threatens legal action against law enforcement officials perceived to be lax in enforcing immigration law. Critics of SB 1070 argue it is the broadest and strictest anti-immigration measure in decades. They further claim it encourages racial profiling. Where did this law come from and how did it emerge so quickly? As Arizona state senator Kyrsten Sinema demonstrates in her chapter, No Surprises: The Evolution of Anti-Immigration Legislation in Arizona, such legislation does not materialize overnight. Rather, momentum builds until the political climate normalizes what previously had seemed unreasonable. Sinema takes readers on a legislative journey by tracing the development of anti-immigrant legislation in Arizona, highlighting the steady, organized movement from the initial introduction of such legislation to the passage of SB 1070 and beyond. Her analysis demonstrates that Arizona’s legislative journey was, in fact, carefully crafted and executed by a coalition of state elected officials and national activists, with the intent to utilize Arizona as a model for other states. Importantly, Sinema’s chapter evaluates the impact of Arizona’s laws on other states and looks ahead to the movement’s next steps in Arizona and beyond.

Consequences for Individuals and Communities

One of the lessons prior research has demonstrated repeatedly is that laws and policies are political, and often symbolic, responses to larger social problems. As such, they frequently result in both anticipated and unanticipated consequences (see, for example, Beckett and Herbert 2008; Chambliss and Zatz 1993; Clear 2007; Fine 2006; Ganapati and Frank 2008; Simon 2007). Immigration law is no exception; indeed, symbolic politics with unintended “collateral” consequences may be the norm when it comes to immigration legislation.

Immigration policy is inherently contradictory as it tries to balance a variety of strains within and among nations. For instance, political and economic relations have created lopsided labor markets and economic opportunities in the global North and South. Looking just within the United States, immigration policies and practices have sought to respond to a number of conflicting needs. These include, for example, religious and ethical demands regarding the place of immigrants in our society and understandings of what constitutes citizenship, the desire for cheap labor on the part of some business sectors (e.g., agribusiness, the hospitality industry, and the meatpacking industry) and individuals (e.g., for nannies, house cleaners, and gardeners), and racialized and gendered educational and employment structures. At the same time, as noted earlier, immigration policies are often reflective of unfounded fears and moral panics (Cohen 1972; Goode and Ben-Yehuda 1994; Welch 2003). As immigration policies attempt to address these often contradictory realities and fears, they can create new sets of problems for individuals and communities (Calavita 1984, 1996; Chavez 2008; Gardner 2005; Johnson 2004, 2007; Newton 2008).

Some of these consequences can be anticipated. For example, individuals who immigrate without proper authorization may be deported and employers who hire undocumented workers may be sanctioned. Individuals make choices in light of these risks. A second set of consequences, while readily apparent, is less likely to be anticipated. These include, for example, the devastating effects of parents’ deportation on children and other family members, some of whom may be citizens. And, because attorneys practicing in criminal or family law may not have a complete understanding of immigration law, they may unknowingly recommend actions that have devastating ramifications for their client’s immigration status.

Yet a third group of consequences are what we call hidden, state-created vulnerabilities. These include harms to individuals (e.g., increased victimization by unscrupulous employers, fear of reporting violence in the home, risks from human traffickers, etc.) and to communities (e.g., reduced willingness of victims and witnesses to report crime, reduced efficacy of the public health sector and school systems because immigrants fear interacting with government employees). In other contexts, these state-created vulnerabilities may include forced relocations and displacement of refugees, rape and other assaults against displaced persons, or finding oneself in unfamiliar and unsafe settings following deportation or relocation.

The chapters included in this section of the volume exemplify some of these anticipated and unanticipated collateral consequences. As a set, they help us understand the myriad ways in which our policies and practices create new dilemmas even as they seek, often unsuccessfully, to resolve other problems confronting societies today. Evelyn Cruz’s chapter, Unearthing and Confronting the Social Skeletons of Immigration Status in our Criminal Justice System, examines the breach of trust that can arise when criminal defense attorneys are unaware of the immigration consequences of the advice they offer to clients. Without such knowledge, attorneys may unwittingly recommend legal actions that result in deportation and permanent bars against re-entering the country. Examining just such a situation in the case of the Postville workers, Cruz takes us beyond the consequences for individuals to help us confront the ramifications for our legal order when clients cannot trust that their attorneys will give...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- 1 Introduction

- Part I New Modes of Control

- Part II Consequences for Individuals and Communities

- PART III Layered Realities

- ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX