![]()

1

Tender Angels, Insensate Pickaninnies

The Divergent Paths of Racial Innocence

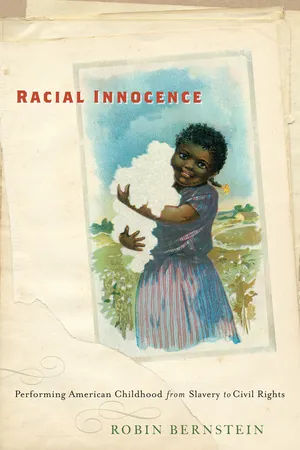

In an advertising trade card from the 1890s, an African American girl smiles as she cuddles an armful of cotton (figure 1.1 and plate 1).1 She advertises Cottolene, a lard substitute made out of cottonseed oil and animal fat.2 The girl is well dressed and also well fed, as her chubby face and limbs attest. A yellow flower decorates her pigtail. The girl replicates the qualities of cuteness that coalesced at the turn of the twentieth century: her eyes are large in proportion to her head, her nose is small, her face is broad, her lips are plump but not to the point of caricature, and her expression is serene.3 Dimples lightly accentuate her round cheeks and elbows. The girl holds the cotton as if it were a baby; the cotton seems almost to snuggle against the girl, to return her embrace. Everything—the girl, the cotton, the countryside—is soft and clean. It is hard to imagine a more tender, appealing image of child labor.

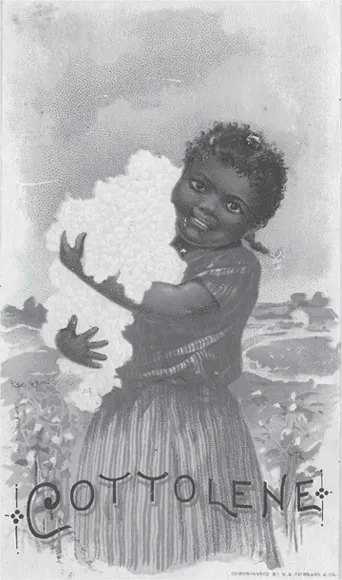

A 1916 photograph of a white girl picking cotton (figure 1.2) pictures the pain and poverty that the Cottolene trade card screens out.4 The photograph is attributed to Lewis Hine, a documentary photographer in the tradition of Jacob Riis. Hine was a social reformer who used his camera to reveal the lives of laborers. Beginning in 1907, Hine worked for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), for which he is believed to have produced this photograph of Callie Campbell, age eleven. Callie Campbell is as thin as the Cottolene girl is plump, and the photograph’s caption makes plain the white girl’s feelings about her labor: “No, I don’t like it very much.” The Cottolene girl, in contrast, has no cause for discontent: in her fantasy milieu, cotton bolls puff out of the plants; they seem to give themselves up, almost to pick themselves. In contrast, the cotton plants that surround Callie Campbell are straggly and low to the ground; she must stoop to pick them. The Cottolene girl stands front and center, meeting the viewer’s gaze; like the cotton plants behind her, she withholds nothing from the consumer. Campbell, however, crosses one arm in front of her body and lowers her head, frowning suspiciously at the photographer. Hine carefully includes signs of Campbell’s suffering within his frame: a bonnet inadequately defends against the sun; long sleeves fend off the plants’ prickles; and Campbell drags a sack that is longer than she is tall.5 The caption specifies the bag’s weight and juxtaposes the high poundage with the girl’s young age: “Callie Campbell, 11 years old, picks 75 to 125 pounds of cotton a day, and totes 50 pounds of it when sack gets full.” In contrast, the Cottolene girl’s puffy cotton seems weightless, even cloud-like. The black girl’s labor is unlabored; the white girl suffers under her burdens. Hine’s image protests the use of an innocent white child as labor; the Cottolene advertisement sells a black child’s labor as innocent.

Figure 1.1. An African American girl cuddles a puff of cotton. Trade card for Cottolene, a lard substitute. N. K. Fairbank and Company, circa 1890s. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Figure 1.2. Photograph of child laborer, taken for the National Child Labor Committee, attributed to Lewis Hine, 1916. The photograph’s original caption reads, “Callie Campbell, 11 years old, picks 75 to 125 pounds of cotton a day, and totes 50 pounds of it when sack gets full. ‘No, I don’t like it very much.’” Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection.

Together, these two images emblematize the flexibility of ideology at the conjunction of childhood and innocence. Childhood in combination with innocence was able to figure, by the turn of the century, in sharply differing political agendas (for and against child labor, in this example) because of the ways in which the concept of childhood innocence changed during the nineteenth century. This chapter charts those changes, arguing that in the second half of the nineteenth century, pain functioned as a wedge that split childhood innocence, as a cultural formation, into distinct black and white trajectories. White children became constructed as tender angels while black children were libeled as unfeeling, noninnocent nonchildren (and this dyadic divergence, a “melodrama in black and white” in Linda Williams’s term, largely erased nonblack children of color from popular representation). Through this polarization, racial innocence—that is, the use of childhood to make political projects appear innocuous, natural, and therefore justified—emerged.

Neither black nor white childhood was monolithic in representation, and certainly not in lived experience, during this period. Representations of white children especially diversified during the second half of the nineteenth century—so much so that Catherine Reef characterized the period of 1860 to 1905 as an “age of contrasts” in the lives and depictions of (white) children.6 Books about angelic white children shared shelf space with books about bad boys and hoydens, and middle-class children became “priceless,” in Viviana Zelizer’s term, while working-class and poor children sweated in factories and fields.7 Representations of African American children were less diverse, but variation existed here, too. Most depictions of African American children were denigrating, but some authors, white and black, produced fictional black child characters that were complex and mostly or fully realized; examples include Jacob Abbott’s Rainbow and Harriet Wilson’s Frado, to be discussed later in this chapter.8

Representations of white and of black children each varied, then, but not in equivalent ways. White child characters were depicted as innocent (even the “bad boy” that emerged in the final quarter of the nineteenth century in the work of Thomas Bailey Aldrich and Mark Twain was mischievous or wild, a “good-bad boy,” in Leslie Fiedler’s term, rather than truly wicked).9 Only the rarest of white child characters was wholly lacking in innocence, and when such a character appeared, he or she usually met a terrible fate and thus invited the reader to identify against rather than with the character.10 Representations of black children, in contrast, were increasingly and overwhelmingly evacuated of innocence. As Karen Sánchez-Eppler has argued, innocence defined nineteenth-century childhood, and not vice versa; therefore, as popular culture purged innocence from representations of African American children, the black child was redefined as a nonchild—a “pickaninny.”11

The pickaninny was an imagined, subhuman black juvenile who was typically depicted outdoors, merrily accepting (or even inviting) violence.12 The word (alternatively spelled “picaninny” or “piccaninny”) dates to the seventeenth century, at which time it described any child of African descent; in the nineteenth century, the word was used pejoratively and in reference mainly to black children in the United States and Britain, but also to aboriginal children of the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand (in this case, the black-white dyad erases the specificity of nonblack children of color by absorbing them into blackness).13 The word’s origins are disputed, but the term may derive from the Portuguese word “pequenino,” meaning a tiny child.14 Characteristics of the pickaninny include dark or sometimes jet-black skin, exaggerated eyes and mouth, the action of gorging (especially on watermelon), and the state of being threatened or attacked by animals (especially alligators, geese, dogs, pigs, or tigers). Pickaninnies often wear ragged clothes (which suggest parental neglect) and are sometimes partially or fully naked. Genitals or buttocks are often exposed, and not infrequently targeted for attack by animals. In some of the most degrading constructions, pickaninnies shit or piss in public. Of course, no individual pickaninny image includes all these characteristics; and some pickaninnies are constructed as clean, well-dressed, and engaged in domestic chores (this is especially true of pickaninny images emblazoned on kitchen-wares such as dishtowels). Some pickaninny figures are nonindividuated and doltish as cows, but others are clever as monkeys. When threatened, pickaninny characters might ignore danger or quake in exaggerated fear; when attacked, they might laugh or yelp, but in either case, they never experience or express pain or sustain wounds in any remotely realistic way. For example, in E. W. Kemble’s 1898 alphabet book (see Chapter 2), two pickaninny characters play with a gun that accidentally fires.15 As the characters are flung violently through the air, they look angry but not frightened or pained, much less wounded or killed. It is this absence of pain that unifies the construction of the pickaninny across differences. The pickaninny may be animalistic or adorable, ragged or neat, frightened or happy, American or British, but the figure is always juvenile, always of color, and always resistant if not immune to pain.

The pickaninny was a major figure in U.S. cultural history and as such must be taken seriously. Because pickaninnies were juvenile yet excluded from the exalted status of “child,” they seemed not to matter. If, as Kirk Savage has argued, a granite monument declares its own necessity and inevitability, then a trade card emblazoned with a pickaninny claimed to be ephemeral, transitory, consumable, and discardable.16 The pickaninny appeared to be, in all senses of the word, minor. That appearance of insignificance provided cover for a justification of violence against African American children. A focus on the pickaninny intervenes in the scholarly argument that U.S. popular culture has fetishized and commodified the pain of African Americans. Debra Walker King writes that “the pain-free, white American body exists easily in the cultural imagination,” whereas “the black body is always a memorial to African and African American historical pain.”17 Examination of adult-oriented culture amply supports this perspective, but the lens of childhood inverts it. The unfeeling, un-childlike pickaninny is the mirror image of both the always-already pained African American adult and the “childlike Negro.”

Today, the Cottolene girl might seem adorably childlike and not at all like the dehumanized pickaninnies in Kemble’s alphabet book. At the close of the nineteenth century, however, a different mode of vision dominated, and in this context, a representation of a black child could seem adorable but not innocent, childlike, or even human. The writer William Cowper Brann made exactly this point when he wrote shortly before his death in 1898, “There is probably nothing on earth ‘cuter’ than a nigger baby; but, like other varieties in the genus ‘coon,’ they are not considered very valuable additions to society.”18 For Brann, cuteness in no way contradicted or mitigated the categorization of a “nigger baby” as a variety of the animalistic “genus ‘coon,’” nor did the infant’s cuteness imbue it with value. This chapter restores cultural context to make sense of this apparent non-sense, revealing the stakes in representations of black children in the second half of the long nineteenth century. In the context of the history that this chapter maps, the Cottolene girl’s baby-shaped pile of white cotton emerges as arguably more childlike, more innocent, and more deserving of protection than its black, juvenile reaper.

Pain, and the ability to feel it, is what separated Callie Campbell from the Cottolene girl, and pain is what divided white childhood from black childhood in U.S. popular culture. The respective images suggested that Callie Campbell’s labors pained her; she belonged not in the field but in school or at home. The Cottolene girl, in contrast, felt no pain; she belonged exactly where she was. Thus the two images made agricultural labor seem, respectively, unjust for white children because it caused them to suffer and natural for black pickaninnies, who did not suffer. These turn-of-the-century images could function in this way because over the previous half-century, pain became a wedge that split one idea—childhood innocence—into diverging paths that produced opposing meanings in black and white. Pain divided tender white children from insensate pickaninnies. At stake in this split was fitness for citizenship and inclusion in the category of the child and, ultimately, the human.

The Emergence of Childhood Innocence

Human societies have long acknowledged differences between juvenile and mature people (as in the biblical verse, “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things”19). However, the characterization of that difference as innocence versus experience—that is, children’s sinlessness, asexuality, and obliviousness to politics versus adults’ sexuality and worldliness—originated, as historian Philippe Ariès famously showed, with the European Enlightenment.20 In North America, the belief that children are innocent did not become widespread until the late eighteenth century. Before that time, the Calvinist doctrine of infant depravity—the belief that people are born with original sin—dominated. According to this doctrine, children are inherently sinful and sexual and are therefore vulnerable to the worst fate imaginable: if they should die before they achieve Christian salvation, they are doomed to eternal hellfire.21 High child mortality rates motivated parents to limit children’s sinful behaviors by any means, and as early as possible, because a child’s soul literally depended on control of the body. As Karin Calvert has shown, colonial material culture, including swaddling and walking stools, compelled infant bodies into upright positions and thus, parents hoped, hurried children out of uncontrolled, vulnerable infancy and toward mature piety.22 Children were “better whipt, than damned,” as Cotton Mather wrote; and parents who believed similarly sought to extinguish sexual and other misbehaviors through swift corporal punishment.23 Eighteenth-century minister John Wesley famously called upon parents to

Break their [children’s] wills. … [B]egin this work before they can run alone, before they can speak plain, perhaps before they can speak at all...