![]()

1

Anarchy in the USA

Whenever governments have imposed sweeping free-market programs, the all-at-once shock treatment, or “shock therapy,” has been the weapon of choice.

—Naomi Klein1

Gimme gimme shock treatment.

—The Ramones, “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment”

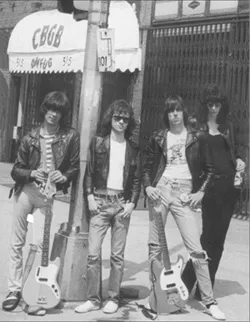

New York City, 1975: The events that would later be heralded as the origins of punk were taking shape. During the previous year, the band Television had begun performing regularly at a music club buried in the depths of the Bowery, CBGB’s. Television’s gigs were soon paired with the Patti Smith Group, and both bands found an audience among New York’s art rock crowd. Meanwhile, four self-styled hooligans from Queens had also formed a band and named themselves the Ramones; by 1975 their performances at CBGB’s—renowned for their ferociousness and brevity—had garnered considerable attention and a recording contract with Sire Records. With their leather jackets, mop haircuts, and streetwise personas, the Ramones’ depiction of juvenile delinquency was balanced by a cartoonish sense of humor, enabling them to personify an emerging punk sensibility of minimalism and postmodern irony.

Before the end of 1975, two local writers had christened the burgeoning New York scene with the publication of a fanzine called Punk. For Legs McNeil, one of the magazine’s cofounders, the term “punk” was used because it “seemed to sum up the thread that connected everything we liked—drunk, obnoxious, smart but not pretentious, absurd, funny, ironic, and things that appealed to the darker side.”2 In 1975, the New York scene comprised an extraordinarily eclectic cohort of musicians—including the preppy Talking Heads, the trashy Heartbreakers, and the sultry Blondie—and thus “punk” was less descriptive of a specific style of music than a general sensibility, particularly one of opposition to mainstream rock music and the hippie culture. A London-based countercultural entrepreneur named Malcolm McLaren visited the New York punk scene twice in the mid-1970s, and according to legend he was captivated by the style of chopped hair and torn clothing donned by Richard Hell, along with the nihilism supposedly expressed in his song “Blank Generation.”3 McLaren exported this look and sensibility back to London, where it created a new style of fashion for SEX, the boutique he owned with Vivienne Westwood. McLaren also drew from Richard Hell and the New York punks in shaping the attitude and music of the band he had begun managing, the Sex Pistols. The rest is punk rock history.4

The Ramones in front of CBGB’s in 1975. From No Thanks! Chrysalis Music, 1978.

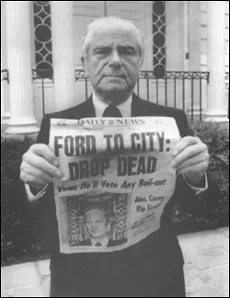

In 1975, the city of New York was also in the middle of a major fiscal crisis that brought it to the brink of bankruptcy. The emergency began when financial institutions refused to continue lending money to the city as its municipal debt grew, and it famously reached its peak in October 1975 when president Gerald Ford rebuffed the city’s requests for a federal bailout, prompting the New York Daily News to run the headline “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.” Deindustrialization had driven the city’s unemployment rate up to 10 percent, and the decline from 7.9 million inhabitants in 1970 to 7.1 million in 1980 represented the largest population loss in New York City’s history. While tax revenues flattened, New York City was also committed to providing an array of public services and municipal jobs that had been secured by a mobilized working class over the course of the twentieth century. As New York plunged into crisis, a cabal of financiers and ideologues seized the opportunity to loosen the city’s responsibility for these public services and employment, thereby remaking New York City into a model of neoliberal capitalism divorced from social democracy and the welfare state. Officials from New York City and New York State did eventually negotiate a loan to avoid bankruptcy, but only after agreeing to severe austerity measures, including cuts in public services.5

New York City’s fiscal crisis became one of the earliest instances of what Naomi Klein has called the “shock doctrine,” in which social or natural disasters provide opportunities for local and global business elites, working with free market ideologues, to dismantle social programs and policies once secured by an organized working class.6 Business elites and right-wing economists used the city’s crisis to seize a larger slice of wealth and undo working-class power in the process. William E. Simon, secretary of the treasury in the Ford administration and a major proponent of laissez-faire capitalism, testified that any federal aid to New York should be on conditions “so punitive, the overall experience made so painful, that no city, no political subdivision would ever be tempted to go down the same road.”7 The restructuring of New York was not simply a grab for wealth and power but also an ideological surge against the perception of the city as a safe haven for lazy welfare cheats, liberal intellectual elites, unproductive union workers, and morally depraved miscreants. The changes instituted during the fiscal crisis included layoffs and wage freezes for thousands of municipal employees, the charging of tuition fees for the first time at the City University of New York, fare hikes throughout the public transit system, and budget cuts imposed on schools, hospitals, and public services. With mass unemployment and a deterioration of services, New York in the mid-1970s is often remembered as a time “when daily life became grueling and the civic atmosphere turned mean.”8

The most desperate conditions were to be found in the South Bronx, where the official unemployment rate among young people reached 60 percent, with even higher estimated rates in some neighborhoods. During the 1950s, “urban renewal” had involved the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, conceived by the city’s notoriously autocratic urban planner Robert Moses. The Cross Bronx accelerated the process of suburbanization and “white flight” while at the same time plunging its surrounding neighborhoods into a downward spiral of economic and infrastructural deterioration. In the 1970s, the economic recession and fiscal crisis suddenly accelerated the processes of deindustrialization and urban decay. The South Bronx was thrust into the media spotlight in 1977, first in July when a power outage led to a night of looting and vandalism, and then in October when sportscaster Howard Cosell announced that “the Bronx is burning” as a fire broke out near Yankee Stadium during game 2 of the World Series. But in reality the immolation of the South Bronx had been ongoing for years, as some 30,000 arson fires were set between 1973 and 1977, typically at the behest of landlords seeking to collect insurance money. The South Bronx thus emerged as a tragic symbol of the shift in American urban policy from a “war on poverty” to “benign neglect.”9

As the punk scene was developing in lower Manhattan, the elements of what we now know as hip hop music and culture were coming together around the same time in the Bronx. In 1973 DJ Kool Herc began hosting parties with his sister, Cindy, in the recreation room of her apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue—now officially designated by the New York State Office of Parks Recreation and Historic Preservation as the “birthplace of hip hop”—and it was here that Herc developed his style of isolating and repeating the instrumental breaks on funk records to provide dancers with prolonged periods of rhythmic intensity. As these dance parties became increasingly popular, Herc moved his sound system into the streets and plugged into lampposts to generate power. Meanwhile, since at least the late 1960s some disempowered young people had been spray painting their signature “tags” on New York City subway trains in what could be seen as pleas for visibility and efforts in spatial mobility. Such graffiti art was a crucial source of inspiration for early hip hop culture in celebrating the command of urban space, the stylish “making a name” for oneself, and the defiance of police and state repression. During the second half of the 1970s, the practices of break dancing, deejaying, graffitiing, and rapping became the focal points in a transformation of social relations among African American, African Caribbean, and Puerto Rican youth concentrated in the Bronx. These social relations took the form of “crews” that competed with one another in displaying their graffiti or break-dancing skills, with DJs fashioning an accompanying musical mix of beats, raps, and turntable scratching. DJs battled for followers and jurisdiction over neighborhoods in the way that street gangs had done, most prominently in the case of the Zulu Nation, founded by Afrika Bambaataa to redirect youth in the Bronx from gang violence to rap music with an Afrocentric message.10

NYC mayor Abraham Beame holding the infamous issue of the New York Daily News. Mayor Beame ripped up the paper after the photograph was taken. From Working Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II. Joshua B. Freeman. New York: The New Press, 2000.

Subcultures and Music in the Age of Neoliberalism and Post-Fordism

In this book my aim is to illuminate the points of intersection between music and youth subcultures on the one hand and the transformation of political economy and social structure on the other. With regard to the latter, I refer to neoliberalism and post-Fordism as a series of economic and political changes that began in the mid-1970s. Neoliberalism is an economic theory that champions privatization and condemns state interventions in the free market, and as official policy it has been imposed by the institutions of global finance and trade (the World Bank, IMF, and WTO) with a fundamentalist zeal since the 1970s, when neoliberals began gaining the upper hand in their offensive against Keynesianism.11 Following the work of David Harvey, I contrast the age of neoliberalism with the “embedded liberalism” that was instituted after World War II, which was distinguished by greater state intervention in capitalist economies and a sort of class compromise among capital, the state, and organized labor. Embedded liberalism produced high rates of economic growth throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s, but it began to show signs of malfunctioning in the late 1960s before plummeting into “stagflation” (an unanticipated combination of inflation and high unemployment) in the 1970s. The failures of embedded liberalism gave momentum to the neoliberal theory espoused by Milton Friedman and other economists at the University of Chicago, whose ideas were applied in renewed attacks against labor and the welfare state, beginning in Chile after the overthrow of the Allende government in 1973. The fiscal crisis of New York City in 1975 can also be seen as a pivotal moment in this transition, as Harvey has argued:

The management of the New York fiscal crisis pioneered the way for neoliberal practices both domestically under Reagan and internationally through the IMF in the 1980s. It established the principle that in the event of a conflict between the integrity of financial institutions and bondholders’ returns, on the one hand, and the well-being of citizens on the other, the former was to be privileged. It emphasized that the role of government was to create a good business climate rather than look to the needs and well-being of the population at large.12

The change from Fordism to post-Fordism is related to the rise of neoliberalism, but more pertinent to the social processes of production and consumption than to the relation between states and markets. Fordism took its name from Henry Ford’s strategy to pay his autoworkers five dollars per day in 1914 in the hope that high wages would allow workers to become consumers of the very products they were being churning out on the assembly line while also ensuring submission to the discipline necessary for mass production. Fordism subsequently took shape as a system of mass production and mass consumption, and in later decades it dovetailed with Keynesian strategies to stimulate consumption through government spending. After World War II, government subsidies for housing, education, and highway construction, coupled with steadily increasing wages, increased consumer demand by swelling the ranks of the middle class. With the crisis of the 1970s, however, mass production began to be forsaken in favor of more “flexible” strategies of accumulation with the crucial advantage of enhancing capital’s spatial mobility in the search for cheap labor. The breakdown of Fordism has been followed by an increasing reliance on outsourcing and subcontracting, as the post-Fordist political economy depends on greater numbers of temporary and part-time workers who are easily disposable and usually not entitled to good wages or benefits. At the same time, in the realm of consumption, the mass markets and mass culture of the mid-twentieth century have splintered into an array of niche markets and lifestyle cultures. Thus, the changes in production and consumption, or work and leisure, have been mutually reinforcing in creating a form of social life that is more fragmented, decentralized, impermanent, and individualized.13

As revealed by David Harvey’s analysis, neoliberalism and post-Fordism are complementary terms that describe different aspects of the restructuring of capitalism that has taken place since the 1970s. In total, this process of restructuring has allowed transnational corporations to extend their global reach, granted capital greater autonomy from regulation by the nation-state, privatized resources and formerly public industries, eviscerated the welfare state and social democracy, disenfranchised organized labor, accelerated the commodification of everyday life, exacerbated inequalities of wealth, and supported a culture of antisocial individualism and materialism. Such changes cannot merely be described as “economic,” for they have given rise to a whole way of life where time and space are compressed, social relations are more fluid and ephemeral, and the commodity form infiltrates every aspect of everyday life.

As New York City became a test case for neoliberal and post-Fordist restructuring after the fiscal crisis of 1975, the punk scene of the 1970s has also come to be seen as both a beginning and an endpoint in the history of rock music and subcultures. The musicians in the New York scene sought to create sounds that were distinct from the forms of rock music that by the mid-1970s had achieved a dominant position within the music industry and FM radio. Although the New York scene accommodated a range of musical styles—from the sinewy guitar epics of Television and the dreamy retro pop of Blondie to the brutish racket of the Ramones—there was a general consensus about the exhaustion of mainstream rock music and the desire to create something different. Likewise, there was a collective feeling that the styles and sensibilities of hippie culture had become stagnant or even reactionary within the social context of the 1970s—that the “counterculture” had been absorbed by the commercial culture. Punk therefore comprised darker and more threatening forms of imagery than did the colorful and mellow hippie culture. For these reasons, the emergence of punk has been seen as a response to the demise of rock and the failure of Sixties utopianism.

My argument is that rock music and the hippie counterculture were shaped by a rebellion against the qualitative consequences of Fordism and embedded liberalism, and that punk was the signal that these movements were exhausted and co-opted in the new social context of the 1970s. By “qualitative consequences” I mean the ways that young people rebelled against the forms of meaning and identity set out for them by the new middle-class and mass society after World War II—the soulless consumer materialism, the rationalization of education, the conformity of the “organization man,” and so forth. Although the counterculture represented a revolt against the “technocracy,” to use Theodor Roszak’s terms, it was also a product of that postwar system, for its optimism and self-importance depended on the apparently limitless abundance of the American economy, which privileged young people and allowed them to experiment and “drop out.”14 The Sixties counterculture mocked the stability and predictability of Fordism and embedded liberalism while taking their productivity for granted, thus creating visions of a postmaterialist future where the values of leisure, spontaneity, and self-expression would triumph over work, discipline, and instrumental rationality. By the mid-1970s, the counterculture’s utopian vision had been exhausted, and a collective sense of dread had developed with the onset of economic recession, political crises, and cultural malaise. The Fordist economy and mass society against which young rebels had defined themselves was disintegrating into a new system of individualized labor and niche markets that could more easily incorporate the symbols, rhetoric, and music of the counterculture into the consumer culture and the creative economy. During the 1970s, the counterculture dissolved into a hodgepodge of spiritual, ecological, and artistic movements, and rock music was solidified as a commercial genre at the center of the lucrative music industry and gradually became distanced from the Sixties’ call to social change. Punk arrived in this context with the message that rock was corrupted and possibly even “dead,” hippies were the new “mainstream,” and society was regressing to a meaner and more chaotic state that made the counterculture’s utopianism irrelevant.

After Malcolm McLaren brought it across the Atlantic, punk took root amid a social crisis in the United Kingdom that had similar origins but was much more dramatic and devastating than the one affecting the northeastern United States at the time. An incipient scene may have been thriving in New York by 1975, but punk did not fully enter the spotlight of popular culture until late 1976 and the tumultuous year of 1977, specifically with the emergence of the Sex Pistols and all the assorted scandals surrounding them. This was a time when unemployment levels reached their highest levels in the...