![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Success of Italian Winemakers in California and the “Pavesian Myth”

THE ITALIAN SWISS COLONY, THE ITALIAN VINEYARD COMPANY, AND THE E. & J. GALLO WINERY

March 12, 1881, provides a convenient and definitive start date for the history of the Piedmontese immigrant presence in the California wine industry. On that day, the Italian Swiss Colony was incorporated in San Francisco, with its premises to be established on the gently sloping hills of the Russian River Valley, eighty-five miles north of the city. The idea for the enterprise had been hatched among the Italian immigrant merchant elite of San Francisco as an ethnic utopia; a community-bred company that could both provi3de jobs to Italian immigrant workers with experience in viticulture and reward its ethnic financial backers with a decent return on their investment. The original promoter of the enterprise was Andrea Sbarboro, a merchant and banker who had immigrated to San Francisco from a village in western Liguria as a boy. Using a modest amount of capital provided by the circle of northern Italian businessmen with whom he mingled in the city, Sbarboro acquired fifteen thousand acres of land in Sonoma County, just south of Cloverdale. He then brought in a handful of northern Italian immigrant laborers and renamed the site Asti in honor of the Piedmontese town famous for its wines. The substantial and steady growth of grape prices on the San Francisco market during the 1870s had inspired Sbarboro to focus his enterprise on grape growing. However, not only did grape prices proceed to plummet during the following decade, but the company’s first crops were a considerable disappointment. The only reason the Italian Swiss Colony even survived these early years was thanks to additional injections of money from the Italian financiers in San Francisco.

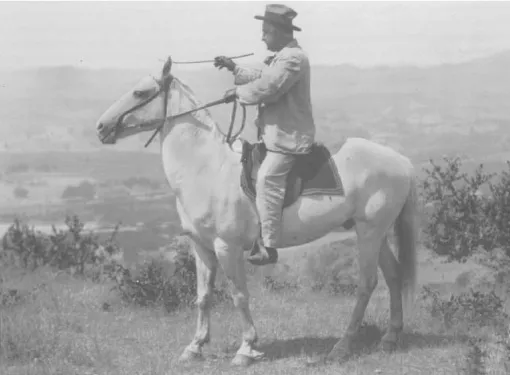

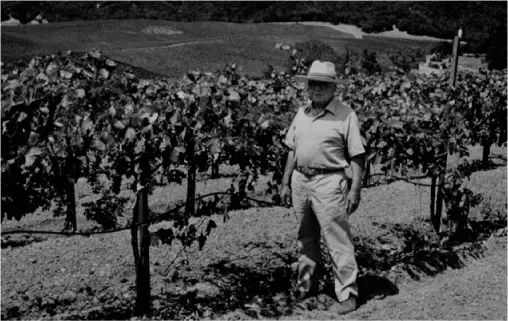

Andrea Sbarboro inspects Italian Swiss Colony’s vineyards at Asti, ca. 1890. Courtesy Alfreda Cullinan/San Francisco Museum and Historical Society.

Pietro Carlo Rossi, ca. 1900. Courtesy Center for Migration Studies, Staten Island, New York.

The turning point for the Italian Swiss Colony’s success was when Pietro Carlo Rossi, a native of Dogliani (in the Langhe) and a pharmacological graduate from the University of Turin, took over the reins in 1888. Rossi wisely decided to transform the company into a winery as a way to cope with the fluctuations of the grape market. Shortly thereafter, he began to experiment with innovative wine-making techniques and made the fateful decision to produce bulk wine and ship it to the vast urban immigrant markets in the Eastern United States. By the end of the century, the Italian Swiss Colony had become the largest winery in California in terms of vineyard acreage, production capacity, distribution network, and market reach. Asti had grown from a plot of land to the size of a small town, complete with Italian school and church. Rossi’s colonial house and Sbarboro’s neoclassical villa, which hosted parties for visiting politicians, diplomats, and royalty, symbolized the settlement’s prosperity.1

Rossi’s sons Robert and Edmund took over the company after their father’s sudden death in 1911 and continued to employ prevalently Piedmont-born immigrants as both laborers and winemakers. Some of these employees, like Edoardo Seghesio, went on to found their own independent wineries; others, like Joe Vercelli, pursued careers as highly skilled winemakers.2 Prohibition was naturally a major shock when it came to the company’s prospects for growth, inaugurating a more complicated period in its history. In 1920, a few months after total Prohibition came into effect, a four-way partnership was formed by the two Rossi brothers, the then-superintendent Enrico Prati, and Edoardo Seghesio, under the name Asti Grape Products (the Dogliani-born Seghesio, who was a relative of the Rossis and Prati’s father-in-law, dropped out of the partnership just one year later). The company survived this period remarkably well by selling grapes, grape juice, and grape concentrate to its already-consolidated market for domestic wine production and use (permitted as an exception to the Eighteenth Amendment in the amount of two hundred gallons per family per year), and it resumed its old name of Italian Swiss Colony at the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. After relaunching the company as a leading U.S. winery following the repeal of Prohibition, Robert and Edmund Rossi ceded control to the National Distillers Corporation in 1942.3 The company went back into family hands in 1953 when it was sold to another conglomerate, the United Vintners Company, and Pietro Carlo Rossi’s grandson, Edmund A. Rossi Jr., took over as vice president and director of quality control.4

The Italian Vineyard Company would get its start nearly twenty years later and some six hundred miles further south on flat, sandy, barren land in the San Bernardino Valley, a hundred miles northeast of Los Angeles. Despite such different environmental and climatic conditions, the winery would come to have much in common with its Asti-based rival. In 1881, the same fateful year the Italian Swiss Colony was founded, future Italian Vineyard Company founder Secondo Guasti emigrated from his birthplace of Mombaruzzo d’Asti, leaving Italy on a ship headed for Panama. In 1883, after brief and discouraging stays in San Francisco, Mexico, and Arizona, Guasti arrived in Los Angeles, where he found work as a cook in an Italian-owned hotel–restaurant. After marrying the owner’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Louisa Amillo (1872–1937), he began working as a wine merchant.5 In 1900, Guasti, like Sbarboro before him, used capital provided by predominantly Piedmontese immigrant investors to buy a vast plot of land split off from a former Mexican rancho in South Cucamonga, where tracks for the Southern Pacific Railroad were just being laid.6 By the end of the decade, Guasti’s grapevines had expanded so far as to garner the distinction of forming the “largest vineyard in the world.” Like Asti in Sonoma County, Guasti’s property had expanded to the size of a small town. Indeed, Guasti was so proud of his accomplishments that he renamed the township after himself.7 It, too, became a company town assembled around the winery, a church, a school, and the house of the founding father, where receptions were held for local dignitaries and visiting Europeans. Some of Guasti’s Piedmontese employees likewise went on to open their own wineries. Giacomo and Giovanni Vai, natives of San Mauro Torinese, acquired the North Cucamonga Winery, where they made tonics, sacramental wine, and other products that managed to pass through the legal net of Prohibition. Giovanni De Matteis of Viale d’Asti, one of the Italian Vineyard Company’s first shareholders, also ran the Italian American Vineyard of San Gabriel during the 1920s and 1930s.8 Finally, most of the Italian Vineyard Company’s early laborers were also Piedmontese immigrants whom Guasti had specifically called to Los Angeles. Unlike what happened at the Italian Swiss Colony, however, where Sbarboro made the strategic and ideological choice to employ a strictly “white” workforce, much of the seasonal field labor at the Italian Vineyard Company was performed by Japanese, and later Mexican, migrants.

Secondo Guasti, ca. 1910. Collection of the author.

Secondo Guasti Sr. died without witnessing the repeal of Prohibition that he had long hoped for, and management of the company passed to his son, Secondo Guasti Jr. Upon the latter’s premature death in 1933, the Italian Vineyard Company entered a phase in which it repeatedly changed hands. In 1957 it came under the control of the Brookside Winery owned by Franco American Philo Biane and Piedmont native Joe Aime. The company was eventually absorbed by a series of large financial corporations in the wine and food sector, while the area of Cucamonga gradually declined as a region for extensive grape cultivation. Today, only a few relics remain of Guasti’s winery and the once largest vineyards in the world.9

The E. & J. Gallo Winery, founded by the brothers Ernest and Julio Gallo, started right where Rossi’s and Guasti’s efforts had been forced to leave off—the hiatus of Prohibition. Reaping the fruits of these pioneering attempts to build a national wine market in the United States, the Gallo Winery went on to achieve extraordinary results. Today, the company is a winemaking colossus that employs more than five thousand people worldwide, owns more than fifteen thousand acres of vineyards across the state of California, and sells seventy-five million cases of wine per year in the United States and ninety other countries, for a total yearly revenue of $1.5 billion. The winery’s roots can be traced back to 1900, when Giuseppe Gallo (1882–1933), one of seven children born into a family of butchers, horse traders, and tavern keepers, left the his native rural town of Fossano, Piedmont, for the United States. Giuseppe (who by then went by the name of Joe) eventually arrived in California after spending time in Venezuela and Philadelphia. He spent his early years in the United States working various pick-and-shovel jobs before entering the petty commerce of wine with his younger brother Michele (Mike) (1885–196?) and becoming a saloon keeper in various boomtowns on the California mining frontier. In 1908, Joe married Assunta (Susie) Bianco (1889–1933), the daughter of an immigrant farmer from Agliano d’Asti. With the substantial help of his young wife, Joe ran a number of different saloons and boardinghouses (informal hotels for single migrants) up and down Northern and Central California before Prohibition forced him out of the trade. Joe had just started his own grape-growing business when Ernest and Julio were born a year apart in the town of Jackson, at the foot of the Sierra Nevada, and he began training them as vineyard workers at a very young age.

Ernest Gallo with collaborators, ca. 2005. Courtesy Associated Press.

Ernest and Julio’s life was to be indelibly marked by their parents’ dramatic death, which was ruled as a murder–suicide. In June 1933, Joe Gallo apparently fatally shot his wife before turning the gun on himself. Just weeks later, the two brothers founded their winery in Modesto. While the Eighteenth Amendment had just been repealed, as promised by newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the market for wine had shrunk significantly since the pre-Prohibition era. The Gallos made it their mission to expand and dominate that market through the vertical organization of their company’s departments, large-scale production, and mass marketing. The first of their products to become vastly popular were sweet, sparkling, and fortified wines whose main consumers were poor minorities in decaying inner cities. But substantial acquisitions of vineyards in California’s Central Valley and the renowned wine regions of Sonoma and Napa; innovative quality research originally overseen by Julio; and aggressive marketing strategies masterminded by Ernest gradually transformed the Modesto-based winery into a brand that met the tastes of more discriminating consumers while still holding mass-market appeal. Over the years, the E. & J. Gallo Winery has become renowned for remaining in family hands despite its massive growth. Indeed, by the time Ernest Gallo died in 2007, the company’s brands and divisions were being run by as many as sixteen different family members spanning three generations.10

Julio Gallo inspects a vineyard of the E. & J. Gallo Winery, 1992. Courtesy Corbis.

WHERE THEY CAME FROM: PIEDMONT, ITALY

The successes of Piedmontese winemakers and their placement within California’s racial and socioeconomic hierarchies must be understood within the historical context of Piedmontese migration to the United States and elsewhere. Despite hailing from the comparatively richer Northern section of the Italian peninsula, Rossi, Guasti, and the Gallos came from a place where la miseria—extreme poverty—was almost as prevalent as in the parts of Southern Italy that have been most often the subject of the histories of Italian immigration to the United States. In the rural surroundings from which they departed, migration was a common experience that touched the daily and emotional lives of those who left as well as those who stayed.

Piedmont, the northwestern part of Italy, derives its name from its location at the foot (pied) of the Alps, the chain of mountains that separates it from nearby France. The geography of the region is varied, with the mountains in the west sloping down toward the plain of the Po Valley in the east, and the rolling hills of Langhe and Monferrato in the south bordering on the coastal region of Liguria. Most of the recorded history of Piedmont coincides with the House of Savoy, which ruled over the land from 1046 until 1861, when King Victor Emmanuel II became the first King of Italy, thus unifying the country as an independent state. Since 1720, when the Treaty of The Hague handed Sardinia to the Kingdom of Savoy, the state became the Kingdom of Sardinia with the city of Turin as its capital. The political history of the Kingdom of Sardinia, and Piedmont therein, was especially influenced by its proximity to France. Even the dialects spoken in the region derive from French and are more similar to it than to Italian. In 1798, the Napoleonic invasion extended legal reform to Piedmont that provided for the end of the remnants of feudalism and the seizure of lands from the Church. In 1848, King Charles Albert introduced a Constitution (Statuto), inspired by the bourgeois revolutions occurring on the other side of the Alps, which would become the supreme law of the Kingdom of Italy after 1861. On the eve of Italian unification under the Savoy crown (a process in which the military role of the French was also crucial), Piedmont was one of the country’s more developed areas. It boasted industrial districts in Biella and Turin (the Italian capital between 1861 and 1865, home to a population of 175,000), an advanced irrigation system that supported the capitalist agriculture of the Eastern plains, more than one-third of Italy’s railroads, and rates of literacy that widely surpassed the rest of Italy.11

But the economic and social development of the region was far from continuous or homogeneous, and this was particularly true for the struggling Southern part of Piedmont where Rossi, Guasti, and the Gallos were born—Langhe and Monferrato. Today this section of Piedmont is one of the richest in all of Italy and is renowned for its food and wine. Langhe and Monferrato have become the destinations of choice for upscale international tourists interested in exciting local cuisine and sought-after wines—Barolo, Barbaresco, Nebbiolo, Grignolino, Barbera, Dolcetto, Freisa, Arneis, and Moscato. Until globalization, deindustrialization, and economic restructuring changed its social and human landscape, however, Southern Piedmont was long one of the poorest areas in Northern Italy. The mostly hilly provinces of Langhe and Monferrato lie halfway between Turin and Genoa and for centuries endured the dearth and excessive fragmentation of arable plots. Bypassed by industrialization, which did not reach them until after World War II, Langhe and Monferrato suffered from their marginal position in relation to nearby centers of economic activity.

During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Langhe and Monferrato provided large numbers of seasonal migrants to other parts of Piedmont and especially across the Alps in France. For some time each year, local peasants—both men and women—became construction workers, chimney sweeps, silk spinners, wet nurses, street performers, beggars, or rural laborers abroad. They used their income from migrant work to bolster their extremely fragile family economies.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the consolidation of an Italian market for wine, the early industrialization of winemaking, and the damaging effects of the phylloxera blight on competing French vineyards encouraged the intensive development of grape cultivation, consequently converting the local rural subsistence economy into market-oriented crop agriculture. For a while, the introduction of large-scale viticulture seemed to provide hope for the region. By the 1880s, however, many critical factors converged to transform traditional short-range seasonal migrations into a mass exodus to destinations both near and far. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the population of the area grew at a...