![]()

1

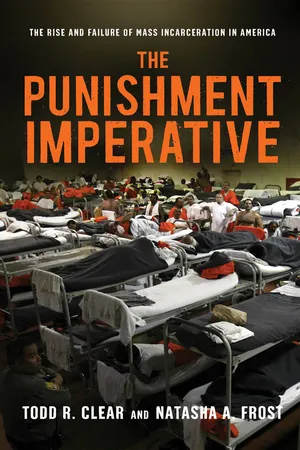

The Beginning of the End of the Punishment Imperative

America’s criminal justice system has deteriorated to the point that it is a national disgrace. Its irregularities and inequities cut against the notion that we are a society founded on fundamental fairness. Our failure to address this problem has caused the nation’s prisons to burst their seams with massive overcrowding, even as our neighborhoods have become more dangerous. We are wasting billions of dollars and diminishing millions of lives.

—Senator Jim Webb, March 3, 20091

In the early 1970s, the United States embarked on a subtle change in the way it punished people for crimes. The prison population, stable for half a century, shifted upward. At first, this was little noticed, so much so that even as the number of people behind bars was inching upward, prominent criminologists were hypothesizing that there was an underlying stability to the use of imprisonment across the United States.2 By the end of that decade, the change was no longer subtle, and commentators began to describe a new harshness in the U.S. attitude toward crime and justice.

In the next chapter, we tell the story of the special character of American punitiveness. It is an extraordinary story of remarkable raw numbers that are all the more astonishing for the way we have gotten used to them. As we shall show, nowhere else in the democratic world, and at no other time in Western history, has there been the kind of relentless punitive spirit as has been ascendant in the United States for more than a generation. That relentless punitive spirit is the philosophy—the point of view—that we call “The Punishment Imperative.” It has been the rationale for mass incarceration.

The short story is that this “new” attitude has become old; the punitiveness of the 1970s was nothing compared with the years to come. For the next forty years, virtually every aspect of the punishment system, from the way people were processed before trial to the way people were confined after conviction, grew harder. Like a drunk whose life descends increasingly into the abyss, U.S. penal policies grew steadily and inexorably toward an ever harder edge. Thresholds of punitiveness people never thought our democracy would ever have to confront became a part of official policy: life without parole and death penalties for young people; lengthy detention before trial; humiliation and long periods of extreme isolation during confinement; decades behind bars for minor thefts and possession of drugs. Such developments would have been unthinkable in the 1960s, but they would become the leading edge of penal reform in the years that followed.

We argue that it is useful to think of this period in U.S. penal history as a kind of grand social experiment that we call “the Punishment Imperative.” As we will argue in more detail in chapter 3, the Punishment Imperative began with the co-alignment of an array of forces that came together to make the explosive growth in the penal system a social and political possibility.3 A decade of rising crime rates fueled public alarm about basic safety, and crime also came to stand as a symbol for the disruption of standing patterns of entitlement and privilege. Media attention to victimizations by those who were formerly incarcerated fueled national sympathy for a victims’ rights movement in the criminal justice system. A nonpartisan consensus developed that addressing crime and fear of crime was a high political priority. The emergence of a large pool of young black men who were unconnected to the labor market provided a group that could serve as a symbolic enemy around which to rally political forces and carry out a “war,” but they were also a tangible target group that required some form of practical social control. The political economy made get-tough politics a successful strategy. Economic growth made penal-system investment possible, and working-/middle-class job creation resulting from that growth provided further energy for an ever growing penal system.

Certainly, the story of the Punishment Imperative can be (and has been) told with different emphases and redirected nuances, but any version of the story will have to offer some aspect or another of the scenario above. The times came together to enable a great, though poorly articulated, social experiment in expanded social control. It has now been going on for almost forty years.

As we write, there are signs—strong signs—that the experiment is coming to an end. As we will argue, a combination of political shifts, accumulating empirical evidence, and fiscal pressures has replaced the commonsense idea that the system must be “tough” with a newly developing consensus that what has happened with the penal system can no longer be justified or sustained. Without fanfare, the results of the great punishment experiment have begun to come in, and they are in ever so many ways disappointing. The emotional and practical energy for punitive harshness, seemingly irresistible just a short time ago, now is oddly passé.

Indeed, the entire corrections system is, for the first time in more than a generation, shrinking. In the years 2009 and 2010, the number of people in both prisons and jails dropped—about 2 percent each year. In 2009, the number of people on probation and parole also dropped (about 1 percent), meaning that in 2010, for the first time in thirty-eight years, the number of people under correctional authority at the end of the year was smaller than the number at the beginning of that year.4 This marks, we think, the unofficial “end” of the Punishment Imperative.

This book, then, is about the rise and fall of the Punishment Imperative. Volumes have been written about what the world has come to see as the special American punitiveness.5 No other nation can tell quite the same story. What makes our retelling of this story useful, we hope, is that we offer it at a significant moment in the narrative of that story—its waning. Our plan is not just to document the character of the special American punishment era but also to show how its development, over time, produced the dynamics that inevitably fueled its conclusion.

This is not to say, of course, that the special American punitiveness has stopped in the same way one turns off an overhead light. The public sentiment for harsh treatment of people who break the law remains deeply seated in the political mind and social character of the nation. Moreover, the consequences of American punitiveness run far too deep and spread far too broadly to be easily discarded. Given these realities, the end of the grand experiment will feel less like a lightbulb being turned off and more like the slow cooling of a white-hot oven.

In fact, the waning of the punitive ethic has been going on for a while. At its height, in the 1980s, the correctional growth rate was typically as high as 8 percent per year or higher, but we have not seen that kind of growth rate for more than a decade. For the last ten years or so, the system has been more likely to grow at around 2 percent a year. This is the statistical evidence that suggests we have reached a watershed point in U.S. correctional history, when the steady rise in imprisonment shifts to a steady—if less steep—decline. The decline in the overall correctional population is but the current realization of a longer trend, in which the steam behind the Punishment Imperative has been declining for some time. Indeed, today’s drop in correctional populations is consistent with a gradual decline in growth that has been going on since at least the beginning of the 2000s. The so-called fall, then, of the punishment agenda has been going on for some time, but its existence was masked by the fact that numbers continued to grow even as the energy for growth was dissipating.

In just the past couple of years, it seems we have reached a turning point in discourse around mass incarceration in particular. For many years, scholars of penology published books describing and seeking to better understand the impetus for the growth in punishment that resulted in mass incarceration. Scholarly attention then turned to documenting the deleterious effects of mass incarceration for individuals, families, and communities—with scholars documenting the ways in which mass incarceration had a tendency to exacerbate some of the most vexing social problems of our times. Today, though, we are increasingly seeing scholars write about reducing our reliance on incarceration and offering strategies for accomplishing meaningful reductions in prison populations without compromising public safety.6

And scholars are not the only ones with voices in this chorus. Journalists too have begun to publish feature stories profiling people and places that are trying to move away from incarceration and find new or innovative ways to deal with crime when and where it occurs.7 Politicians are increasingly less concerned with coming across as “tough on crime” and more inclined to talk about ways to be “smart on crime.” Federal legislation passed in recent years has a remarkably different character than legislation passed just one decade earlier.8 Policymaking in the penal arena no longer consists solely of new ideas for increased punishments. Ideas in good currency today often emphasize lesser punishments as ways to improve public safety.9

The special American punitiveness, ascendant for more than a generation, ran so deeply in the political culture that it still resonates, and many (if not most) people would find it odd to suggest that it is a phenomenon in decline. But it is, in fact, the current political shifts that offer the most convincing evidence that something has changed. In the last three presidential elections, crime has scarcely been an issue. This pattern has been repeated in gubernatorial and other electoral campaigns. States such as Louisiana and Mississippi that reveled in their own homegrown, “get-tough” politics now lead the nation in prison downsizing.10 Their governors announce prison reduction programs, including release programs that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. There was a time when even a hint of a policy that might have resulted in prison releases or reductions in sentencing would have spelled certain political death. Today, at least thirteen states are closing prisons after reducing prison populations.11 That this kind of policy is no longer political anathema is a leading indicator of how much has changed.

What this brief discussion shows is that the Punishment Imperative was a policy experiment. Without question there were changes in the dynamics of crime, but they were tangential to the profound changes in crime policy described in chapter 4 that have dominated the American criminal justice scene for nearly forty years. What happened was a deliberate, if haphazardly conceived, agenda of more and more punishment—a Punishment Imperative. Precisely because this was a policy agenda, rather than some sort of social circumstance, we are able to analyze this time in American history using the grand social experiment framework.

In the remainder of this chapter we describe what we think of as the end of the great penal experiment that took place between 1970 and 2010 and outline the prospects for something new to emerge—something with far less emphasis on prisons and much more emphasis on a conglomerate of correctional approaches. We argue that we have reached an era in which a new milieu is fueling the prison populations and penal system. Although we offer a fuller version of what we think that new model might look like in our concluding chapter,12 the short version would probably read something like this:

The worldwide economic crisis of 2008 has created pressure on U.S. state and local governments to reduce their costs. One of the fastest-growing costs is the prison system, and so there is impetus to control prison costs—and that means reducing the number of prisoners. There is bipartisan agreement that controlling prison costs is an important immediate objective. Because crime has been dropping nationally for more than a decade, the get-tough movement has lost some of its salience with the public (and therefore the politicians). There is a new bipartisan consensus that improving postrelease success for people who leave prison is a high priority, and this has created public support for reentry programs. A plethora of news media stories and social science studies about mass incarceration and the plight of people who have been to prison has balanced the national appetite for victims’ rights with a sentiment that the system has gotten out of control. There is growing belief that the “drug war” has been, if not a complete failure, then at least a mistake. Increasingly, there is a call for correctional programs to be based on “evidence” rather than ideology. One of the most popular new national programs is “justice reinvestment,” which seeks to control the rising costs of prisons and invest the savings in projects that will enhance, rather than further damage, communities.

Justice reinvestment, the emerging model we advocate for in the concluding chapter, offers a new framework for the penal system to approach its work. To the extent that justice reinvestment—or something like it—becomes dominant, it signals a new era: the end, if slow and vacillating, to the grand penal experiment.

The End of an Era: Evidence from the Field

We do not have to look far to see strong evidence that a new conversation has taken hold in penal policy circles. As we write, evidence mounts daily that the experiment is grinding to a halt. As of August 2011, at least thirteen states—one-...