![]()

1

Before the “Caucasian Race”

Antecedents of European Racialism, ca. 1000–1684

Naming occurs in sites, particular places, and at particular times. For a name to do its creative work, it needs authority. One needs usage within institutions. Naming does its work only as a social history works itself out.

—Ian Hacking1

There was no notion of a Caucasian race in the years between 1000 to 1684. In fact, the “race” concept itself was introduced by Europeans elites only near the end of this period, in the seventeenth century, after the rise of the Atlantic slave trade and massive enslavement of “black” Africans. Nevertheless, the ethnic history of Europe during this period, which stretched from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment, was a prelude to the invention of the “Caucasian race” idea in the late eighteenth century and its subsequent career.

Several medieval and early modern European notions about differences and boundaries between peoples established ideational building blocks for modern race thinking. They sustained ethnic divisions within and beyond Europe that later shaped the shifting boundaries of modern racial categories, including nineteenth-century theories about the “races of Europe” that ruptured the preeminence of “Caucasian race” idea. One significant thread of this history was the development of the idea and actuality of “Europe.” After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the region now known as Europe gradually coalesced from great migrations of various peoples who criss-crossed the greater Eurasian landmass during the first millennium, including Angles, Saxons, Celts, Franks, Gauls, and Slavs.

These peoples did not constitute human “races,” and they did not understand themselves as such. Moreover, before the establishment of relatively well defined national “homelands” in the later medieval period, they were constantly in motion in the western (now European) part of Eurasia. Norman Davies comments, “It was difficult for tribes to move without coming into contact, and potential conflict, with their predecessors on the trail. . . . There is absolutely no reason to suppose that Celts, Germans, Slavs, and others did not overlap, and sometimes intermingle. The idea of exclusive national homelands is a modern fantasy.”2 This first great migration period in European history did not really end until “the arrival of Turkic peoples in Greece and the Balkans in the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries.”3 This flux in Europe’s formative period informs its subsequent ethnic and racial history.

A few constellations of medieval ideas and concepts were especially significant for the development of the “race” concept and the shifting boundaries of modern racial categories: the ideas of “Christendom” and, later, “Europe,” which marked a religiously, culturally, and geographically distinct region; the profound (and often racelike) alienness or otherness that various peoples in the Middle Ages sometimes ascribed to other peoples, especially those who did not share their religion; and the fact that European Christians adopted the Judaic account of creation and biblical chronology, along with an Old Testament view of the origins of various tribes of human beings. In addition, Cedric Robinson identifies three historical developments that joined this mix to generate modern racial thought:

the Islamic (i.e., Arab, Persian, Turkish, and African) domination of the Mediterranean civilization and the consequent retarding of European social and cultural life: the Dark Ages; the incorporation of African, Asian, and peoples of the New World into the world system emerging from late feudalism and merchant capitalism [i.e., between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries CE; and] the dialectic of colonialism, plantocratic slavery, and resistance from the sixteenth century forward, and the formation of industrial labor and labor reserves.4

Some of these developments were largely internal to Europe, while the others were indicative of Europe’s competition with the Islamic world and its increasing global power and reach.

Medieval Europeans employed certain racelike ideas to comprehend their social order and differentiate between social groups, but these were ethnic rather than racial designations. Still, a few cases of religious and ethnic conflict in early modern Europe were quite close to modern racism and paved the way for it: Christian anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim ideas and movements that peaked after the fifteenth-century Christian “reconquest” of Spain; associations of “black” Africans with servile status that emerged in the Middle Ages and were compounded when Portuguese sailors acquired West African slaves in the fifteenth century; English Protestant colonial domination of Irish Catholics, particularly between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries; and conflicts between Franks and Gauls and Normans and Saxons in early modern England and France.

By the latter half of the seventeenth century, race-thinking proper emerged. English settlers in colonial America developed a racial understanding of and justification for the perpetual servitude to which they subjected “black” Africans, and they began to define themselves and other Europeans as “white” people. In relation to the new knowledge of the world and its peoples and the new global politics of the age, European scientists built upon the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to develop the new science of “natural history.” They sought to explain the world’s natural order and the place of human beings within this order. One notable product of natural history was the first recognizably modern racial classification, in 1684, by the French travel writer François Bernier.

Europe and Its “Others”

Compared to the steady migrations that characterized Latin Christendom and nascent “Europe” in Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, the feudal social order that developed in this region during the Middle Ages (ca. 750–1453 CE) was relatively static and marked by a deeply sedimented status hierarchy. “The serf, the slave, the peasant, the artisan, the lord, the king—all were allotted their place in the world by divine sanction. Not just human order but natural order was preordained.” All living things were seen as joined in a “Great Chain of Being [that] linked the cosmos from the most miserable mollusc to the Supreme Being.”5 There were also significant distinctions between communities. Ethnocentrism was common between religious and ethnic groups—tribes (gens), peoples (ethne), and nations (natios);6 Christians, Jews, Muslims, and pagans; the “civilized” and the “barbarian.”7

Yet these medieval divisions were different from later racialized divisions.8 This difference, which is important for understanding race and racism, has been obscured in some recent writing about medieval Europe. Robert Bartlett, for instance, examines what he calls the “race relations” of Latin Christendom between 900 and 1250 CE.9 He says that “while the language of race [in Latin Christendom]—gens, natio, ‘blood,’ ‘stock,’ etc.—is biological, its medieval reality was almost entirely cultural. . . . When we study race relations in medieval Europe we are analysing the contact between various linguistic and cultural groups, not between breeding stocks.”10 Bartlett cites the canonist Regino of Prüm’s four criteria for classifying “ethnic variation” as a classic medieval formulation of medieval “race relations.” According to Regino (d. 915), “The various nations differ in descent, customs, language, and law.”11 Bartlett comments that only Regino’s first criterion, “descent,” is central to modern racism, and he goes on to note that “Regino’s other criteria—customs, language, and law—emerge as the primary badges of ethnicity.”12

Bartlett is correct to speak of ethnicity in this context, but he confuses matters by describing medieval Europeans’ notions of ethnic difference in terms of race relations.13 Medieval Europeans, along with the peoples in other parts of the premodern world, lacked any concept comparable to the modern “race” concept. They emphasized cultural criteria of difference and lacked any clearly developed notion of “fixed natures” of different descent groups.14 For instance, medieval Christian Europeans used Arab, Saracen, and later Turk as terms for “Muslim”; Muslims of the Ottoman Empire referred to Europeans as “Franks”; and followers of each religion regarded members of the other faith as “infidels.”15

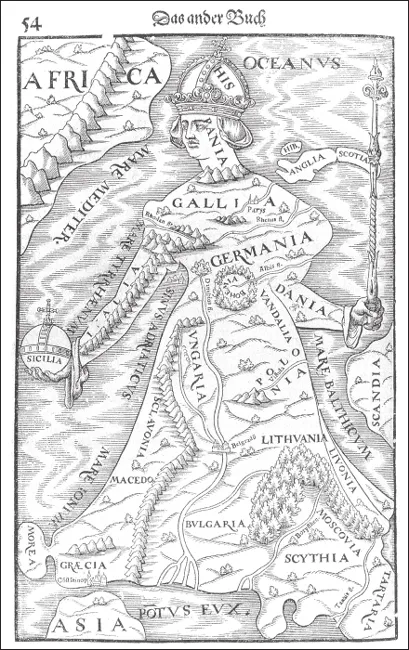

The historical development of the idea and territory of Europe was itself one of the most important antecedents of the modern “race” concept. Europe has sometimes been considered a distinct continent, but this is a misnomer (see figure 1). The region we now know as Europe is actually a peninsula of the Eurasian landmass.16 Europe, as Bartlett says, “is both a region and an idea.”17 The societies and cultures that inhabited the western peninsula of the Eurasian landmass were always diverse. But by the later Middle Ages there was enough commonality among the areas that we now call western and central Europe to constitute a distinct region: “When compared with other culture areas of the globe, such as the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent or China, western or central Europe exhibited (and exhibits) distinctive characteristics. In particular, Latin Europe (that is, the part of Europe that was originally Roman Catholic rather than Greek orthodox or non-Christian) formed a zone where strong shared features were as important as geographical or cultural contrasts.”18

Figure 1: Queen Europe (Regina Europe), from Sebastian Müntzer’s Cosmography (1588). Reprinted from Early Modern Europe: An Oxford History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), ed. Euan Cameron, p. 20 (British Library, MAPS C21 C13).

Europe was becoming a kind of “imagined community” in political scientist Benedict Anderson’s sense: a loose but geographically and culturally bounded society “conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship,” despite having no obvious or natural boundary to its eastern flank and a somewhat indeterminate southern frontier.19 Because of its geographical indeterminacy, the idea and boundaries of Europe have been conceived as much in opposition to other cultural and political zones as in relation to what “Europeans” have had in common. For instance, the status of Russia as properly “European” has long been contested, both within the core of Europe and among Russian intellectuals.20 The “modernizing” regimes of Peter I (Peter the Great, r. 1682–1725) and Catherine II (Empress Catherine, r. 1762–96) “Europeanized” Russia (Catherine declared Russia “a European state” in 1767); yet they did not resolve the issue. Due to this ambiguity, Europe’s “official” eastern frontier constantly shifted. “It advanced steadily from the Don, where it had been fixed for a thousand years, to the banks of the Volga at the end of the fifteenth century, to the Ob in the sixteenth, to the Ural river and the Ural mountains in the nineteenth, and finally to the river Emba and the Kerch straits in the twentieth.”21

To a large extent, the consolidation of Europe was spurred by the rise and expansion of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries.22 The expansion of Islamic societies isolated “Christendom” from the rest of the world and defined Europe’s boundaries. Muslims also established a major presence at the edges of Europe: first in Iberia (in the seventh century) and later in the Balkans and the Black Sea region (in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries) and Hungary (capturing Belgrade in 1521), being repelled at Vienna in 1529 and again, decisively, in 1683.23

Ongoing contact and conflict between Christians and Muslims had a direct impact on the place of the Caucasus region vis-à-vis Europe and Asia. Several centuries of enslavement of Christians by Muslims and of Muslims by Christians, for instance, continued into the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Meanwhile, in the western part of Europe, slavery had largely been done away with between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. This achievement followed the consolidation of a sense of “Christian brotherhood” in opposition to perceived Muslim and Jewish “outsiders.” This new collective identity was exemplified by the Crusades between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. This was the context in which thousands of Caucasians, including Georgians, Armenians, Circassians, and Mingrelians, were bought and sold as slaves, along with the Moors, by Venetian and Genoese merchants. These groups “were classified as infidels even if they were eventually baptized.” Italian merchants “sold such ‘Slavs’ . . ., along with Greeks and Turks, in Muslim markets as well as in Christian Crete, Cyprus, Sicily, and such Spanish regions as early-fifteenth-century Valencia.”24

This source of slaves was mostly abandoned after the Ottoman Turks’ conquest of Constantinople in 1453, which redirected slave traders to sub-Saharan Africa.25 At that time the Portuguese sold increasing numbers of black African slaves. Prior to this Atlantic slave trade, slavery was already a prominent part of the economic and social history of European and Islamic societies in the Middle Ages. Yet racialized slavery emerged only with the development of Atlantic slave trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (see below).

The Caucasus region sits squarely in greater Eurasia, on the isthmus between the Black and Caspian Seas where Europe and Asia meet; but even though it is partly Christian (primarily in Armenia and Georgia), it has never really been considered part of Europe. Christianity was adopted by leaders of Armenia and Georgia in 314 and 330 CE, respectively; Persian (Iranian) influences arrived in the fifth and sixth centuries, and Islam followed in the seventh century.26 After the Ottoman conquest of Const...