![]()

1

Jews, Theatricality, and Modernity

It is well known that throughout the twentieth century, American Jews were deeply involved in the creation of American popular entertainment. Never much more than 3 percent of the population, Jews were nonetheless instrumental in the development of the major industries and entertainment forms that provided mass culture to a majority of Americans through much of the twentieth century: Broadway, Hollywood, the television and radio industries, stand-up comedy, and the popular music industry have all been deeply influenced by the activity of Jews. If we look beyond America’s shores, we find the same story, although not quite to the same extent, in many centers of European culture.1 In the modern era, especially in liberal society, Jews were among the foremost practitioners of the modern theater and by the late nineteenth century were explicitly associated both with the theater and with theatricality throughout Europe and North America. This close connection between Jews and entertainment represented a radical departure from traditional Jewish attitudes toward the theater. This chapter explores why, for centuries, Jews were one of the few European cultures without any official public theatrical tradition. We then look at how the particular historical conditions of Jewish modernity in Europe eventually led Jews to become intimately involved with the theater. Finally, we examine the history of interpretation of the biblical story of Jacob and Esau in order to understand the ways in which Jewish thinkers across the ages have responded to the morally ambiguous aspects of theatricality itself, a mode which encompasses both acting on the stage and performance in everyday life.

* * *

For more than 1,500 years, traditional Jewish authorities were notoriously anti-theatrical. In Warsaw, for example, as late as the 1830s local synagogue councils pressured the city’s police commissioner to forbid Jews to stage theater performances, arguing that such performances would be “an indecent mockery that leads to demoralization and is strictly forbidden by religious laws.”2 Theater did, nonetheless, achieve a carefully circumscribed place within early modern traditional European Jewish communities, bursting forth on the holiday of Purim, when role-playing, pageantry, costumes, and general hilarity were grudgingly allowed by religious authorities, and in wedding celebrations, where the badkhn, or wedding-jester, told stories and jokes, and his accompanying klezmorim (minstrels) performed musical numbers for the bride and groom and their guests. Until the mid-nineteenth century, however, aside from the occasional mention of Jewish actors in court theaters (mostly in Italy) and a lively subculture of traveling jesters, musicians, and magicians, nonreligious theatrical activity was almost nonexistent in traditional European Jewish communities. Constrained by a number of factors, including biblical prohibitions against cross-dressing, rabbinic prohibitions against a woman singing (or, by extension, performing) in public, and the general resistance to any form of intellectual or artistic pursuit that fell outside of the study of Torah, public theatrical entertainment unrelated to Purim did not gain a serious foothold in Jewish life until the advent of the modern period and the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment).3

The rabbis of the Mishna and the Talmud explicitly addressed concerns about the theater in terms of how to regulate Jewish interactions with non-Jews. The theater was assumed to be part of non-Jewish culture, and the rabbis were concerned with delineating how, where, and when Jews were allowed to participate in this often overtly pagan public entertainment. Much of the commentary on the theater, therefore, is located in a tractate of the Talmud devoted to the discussion of idol worship (Masechet Avodah Zera). The Talmud quite clearly forbids Jews from attending the Roman theater for three reasons. First, far from being simply a place of entertainment, the Roman theater was seen as a gateway to a world of idolatrous behavior: the action on the stage might involve human and animal sacrifices, gladiator battles, and actors dressed as gods. The rabbis knew that it was impossible to separate earthly and cosmological concerns in the Roman theater and therefore forbade Jews from participating in, or even watching, these pagan practices.4 Second, even those theatrical productions that did not involve idol worship were forbidden because they were considered pointless entertainment; it was considered inappropriate for Jews to be seen “sitting with fools” (moshav leytzim).5 Those engaged in frivolity were wasting time that could be spent in studying Torah. Third, the Roman theater involved not just plays and ritual sacrifices but also gladiator shows and other forms of violence. The Talmud explicitly implicates those who watch such bloodshed as being complicit with it.6

The level of detail that the rabbis use to explain their prohibitions, however, indicates that Jews were in fact regularly attending the Roman theater. After issuing a blanket prohibition against attending the theater, the Talmud outlines all the different types of theaters, stadiums, and circuses one should avoid, and delineates all the different types of performers who might be considered “frivolous” (such as soothsayers, magicians, clowns, buffoons, actors, and the like), implying close familiarity with a variety of theatrical forms. Indeed, recent archeological evidence not only supports the attendance of Jews at the Roman theater—an inscription in the theater of Miletos, for example, reserves an entire seating area for Jews—but also argues for a Jewish presence in the production of some theater on the basis of a recently identified play from the Hellenistic period titled Exagogue, by a Jew named Ezekiel.7 Hence the need for the prohibition laws. The rabbis also describe a number of loopholes. One might attend the theater, for example, to bear witness to the death of a Jewish man (martyred in the stadium) and thereby prevent his wife from becoming a grass widow (agunah), unable to remarry. The Roman theater likewise was one of the few sites where Jews could publicly participate in the political sphere. When the Emperor appeared at the theater, it was not uncommon for members of the populace to demonstrate or present petitions. The rabbis, therefore, acknowledge that one can attend the theater in order to participate in a crowd that “screams” about troubles to the government. And finally, the theaters were important places of business, and Jews were clearly involved in a number of commercial activities surrounding the theater. The rabbis tried to regulate these practices by indicating that one may make money from “frivolity” but not from idolatry. A Jew can, for example, sell concessions at the theater but may not be in the business of manufacturing the pedestals for idol worship or ritual garments for the practice of idolatry.

Numerous Talmudic legal codes also made it extremely difficult for Jews in the Roman empire, and later in the lands of Christian Europe, to develop a theatrical tradition of their own. Starting from the biblical injunction: “You shall not copy the practices of the land of Egypt where you dwelt, or of the land of Canaan to which I am taking you; nor shall you follow their laws” (Lev. 18:3), the rabbis of the Talmud denoted a wide variety of prohibited practices, many of which prevented Jews from participating in the theaters of the lands in which they lived or from founding theaters of their own. While some of the commentators see this law as referring to idol worship and the practice of forbidden sexual taboos, others use a “slippery slope” argument, widening the prohibition to encompass daily habits (“hukot goyim”) that might present a temptation to follow the ways of the non-Jews. An early midrash uses this law not only to forbid Jews from attending the theaters and circuses of non-Jews but also from copying their fashions.8 Maimonides, one of the most important and respected philosophers in Jewish history and a model for Jewish rationalism in the medieval period, elaborates on the reasons for this ruling, explaining that the goyim are not good role models and one should not strive to imitate them. Jews should not desire to wear purple because the goyim wear purple, or to dress with weapons in order to look like knights. Jews are supposed to be different, Maimonides insists, so why would one want to copy the hairstyles, fashions, or modes of entertainment of the goyim?9 By the sixteenth century, these interpretations were integrated into the strict legal code of the Shulchan Aruch, which forbade particular hairstyles, ways of shaving the head, fashions, and other practices that were considered explicitly non-Jewish. If one were forbidden to dress like the gentiles, it would be difficult to portray a gentile on the stage.10 Jews were also forbidden to build structures that looked like those used for idol worship because the mere presence of such a building might encourage idolatry. Indeed, the modern Hebrew word for stage, bamah, in biblical Hebrew generally referred to an altar used for pagan sacrifices. Theaters and stages were therefore automatically suspect spaces.

The problem of creating a theatrical tradition was further hampered by the laws against cross-dressing and hearing the voice of a woman in public, making it extremely difficult to create a sustainable theatrical tradition if male and female characters cannot be portrayed on the stage together. In many cultures (including that of Elizabethan England), women were banned from acting on the stage, but female roles were still represented—by boys. In the case of traditional European Jewish culture, though, neither option was acceptable. Strict laws of modesty and of separation of the sexes meant that women were not allowed to publicly display themselves in any way. The Talmud assumes that all parts of a woman’s body (even her pinky finger) may serve as sexual provocation, and therefore not only should women dress modestly but men should be careful not to look at women who are not their wives. Needless to say, it was therefore impossible for a woman to perform on the stage and abide by Jewish modesty laws. Likewise, women were not and are still not in Orthodox communities allowed to chant prayers or read from the Torah in the presence of men. The voice of a woman (kol b’ishah) is considered inherently sexually suggestive and a potentially illicit distraction for men, especially men at prayer. But listening to or looking at women for any kind of pleasure—sexual or aesthetic—is frowned upon in multiple sources, one in Shulchan Aruch even insisting that a male should not watch a woman hanging laundry or look at women’s clothes (even without a woman in them!) hanging on a laundry line.11

But the option of using boys to play female roles is also rendered problematic by traditional Jewish law. The Torah clearly forbids cross-dressing: “A woman must not put on man’s apparel, nor shall a man wear woman’s clothing; for whoever does these things is abhorrent (toavat) to the Lord your God” (Deut. 22:5). Much early rabbinic commentary attempts to explain the strong language of abhorrence in this passage (toevah implies an idolatrous act, in this case one with sexual connotations) and deduces that cross-dressing will lead to other sexual sins and thus must be avoided at all cost. The Talmud also explains in detail the kinds of dress that are forbidden for men and women, and extends the prohibition to shaving their hair.12 Medieval commentators further strengthen the prohibition, expressing concern that dressing as the opposite sex will allow one to infiltrate gender-segregated spaces for the purpose of sexual depravity or that cross-dressing could potentially upend the order of creation. One thirteenth-century Italian rabbi, for example, worries that if a man dresses as a woman, his soul might become confused and in the next life return as a woman, or vice versa.13 As we have almost no evidence of theatrical performance in European Jewish communities of the late ancient and medieval period, and therefore no evidence of women performers or boys performing as women, it seems that these prohibitions were both effective and culturally binding, at least in the arena of public performance.

By the early Renaissance, when Purim plays were increasingly gaining in popularity in traditional Jewish circles, the Shulchan Aruch loosened the prohibition on cross-dressing somewhat, permitting men and women to wear masks and cross-dress for the purpose of fun on a festive occasion. As long as a clear distinction was maintained between dressing up for “fun” and dressing up for licentious purposes, there was no reason, according to this code of law, to insist on a blanket prohibition against cross-dressing.14 Purim revelers—all men—enacted the story of Purim by taking on both male and female roles, but men tended to perform female roles in such a way that their maleness was never fully obscured, allowing their everyday clothes and masculine shoes to protrude from the bottom of a dress, or exposing a bit of beard to great comic effect.15 In this way, they managed to circumvent the law while still gesturing at it. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a number of Hasidic scholars began to develop mystical justifications for impersonation along with carefully circumscribed and strategic permission for disguise, imitation, and playacting—but only in the service of spiritual purposes and never simply for the sake of entertainment.16

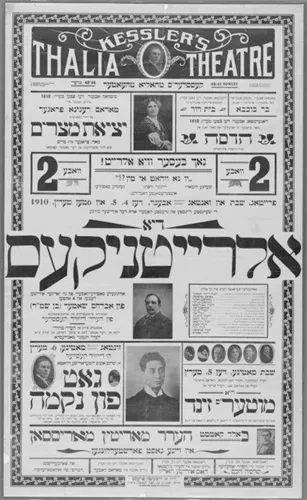

In both Europe and America, the emergence of Jewish culture from this traditional religious context was nearly always accompanied by significant Jewish production of secular theater, and, in particular, plays that explored the ambivalence Jews felt about the shifting identity boundaries characteristic of modern life. In eighteenth-century Berlin, for example, “enlightened” Jewish playwrights (maskilim) used characters speaking multiple languages (French, German, Yiddish, Hebrew) to signify particular attitudes toward religious and public life, and to express their support for enlightenment but ambivalence about assimilation.17 In nineteenth-century Eastern Europe and America, Yiddish-language secular theater, which emerged from the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century tradition of Purim plays but, with the rise of secular Jewish culture expanded to become a full-fledged national theater, was equally obsessed with modernity, religious tradition, and assimilation. In late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century New York, the Yiddish theater played a role in easing the transition for immigrants from a religious to a secular life: the rebbes were replaced by stars and the liturgy by secular melodrama, and Jews who in a previous life might have attended synagogue on Shabbat, now went to the theater. While Jews flocked to the theater on Friday nights, many did not easily make the transition from synagogue to secular entertainment and assuaged their consciences by vociferously condemning the actors on stage for “breaking Shabbes.” The early twentieth-century journalist Hutchins Hapgood noted that “[t]he actor who through the exigencies of his role is compelled to appear on Friday night with a cigar in his mouth, is frequently greeted with hisses and strenuous cries of “Shame, shame, smoke on the Sabbath!”18 On weekends, some theaters offered “semi-sacred” pieces, such as Goldfaden’s Shulamis and The Sacrifice of Isaac, in an attempt to attract more religiously observant customers.19 Many theaters also offered relevant historical plays during the Jewish holidays, but most of the connections between the plays offered on the Yiddish stage and the traditional liturgy were far more subtle. Plays attempted to fulfill the spiritual needs of the immigrant community in new ways. By providing an outlet for deep emotion (both joy and sorrow), a sense of historical Jewish pride, and an escape from the difficulties of the immigrant experience as well as a medium for moral education and a guide to solving the problems of daily life, the Yiddish plays sustained the immigrants spiritually while helping to transform them psychologically into modern American Jewish citizens.

Indeed, Jewish modernity itself can be understood as a kind of theatrical endeavor. Wherever Jews were forced by historical circumstances to adopt double roles and to use performance as a survival strategy, there we see the twin roots of Jewish modernity and Jewish theatricality. Gershom Sholem, for example, argues that we can locate the beginning of modern Jewish self-consciousness in the experiences of those Spanish Jews of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries forced to live as Marranos—Christians in public, Jews in private.20Arguing that Jewish modernity begins with the Sabbatianism that first took root in the diaspora of Spanish Jews after the expulsion in 1492, Scholem writes: “within the spiritual world of the Sabbatian sects . . . the crisis of faith which overtook the Jewish people as a whole upon its emergence from its medieval isolation was first anticipated” (84). Sabbatianism sacralized “necessary apostasy”—essentially formalizing in religious terms the paradoxical Marrano condition of believing one thing while practicing another. Scholem sees both historic and metaphorical parallels between Sabbatian split consciousness and the modern sense of self developed by the maskilim of Berlin. This distinction between “inner” and “outer” selves was later turned into a more general maxim for Russian Jewish modernization by the poet Judah Leib Gordon when he exhorted his fellow Jews to be a “man abroad and a Jew in your tent.”21 That theatrical sense of playing a role in public increasingly pervaded the writing of modernizing Jews and indeed became its defining feature.

This poster from the Thalia Theater advertises a production of Di Alraytniks, a comedy of assimilation, alongside Exodus from Egypt, a more religious play. (The Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library, Astor Lenox and Tilden Foundations.)

* * *

The doubleness inherent in modern Jewish life laid the groundwork for the emergence of new or dormant Jewish attitudes toward performance and theatricality. The Jewish interpretive tradition has alwa...