![]() PART I

PART I

THE FIRST DEPARTMENTS

Medicine and Surgery![]()

THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE

1

The Leadership of the Department of Medicine

OF ALL OF the “Giants” in Mount Sinai's past, few were bigger than the ones that ruled the medical wards at Mount Sinai. Names such as Libman, Brill, Baehr, and Oppenheimer would all find a place in a “Who's Who” of twentieth-century medicine. There were several factors that brought them to Mount Sinai during the first decades of the 1900s. The first was the stature of those who had come before: Abraham Jacobi, Edward G. Janeway, Alfred Loomis, and Alfred Meyer. There was the sense at Mount Sinai of being a member of an elite group of physicians, carefully selected and trained, nurtured with additional training abroad and then moved up the ranks. Also, there was the relentless anti-Semitism that kept some from pursuing residencies at other hospitals. It was clear that if one were a young Jewish physician with high ambitions, the wards of Mount Sinai were the place to be.

The groundwork for this environment was laid by the first physicians who staffed the Hospital at its opening in 1855. During the first fifty years of the Hospital's existence, it was not unusual for the physicians to be general practitioners in the broadest sense, seeing patients of all ages and performing deliveries and minor surgeries as needed. Abraham Jacobi, the “Father of American Pediatrics,” was on Mount Sinai's staff for almost twenty years before he was given the title of Pediatrician. Prior to this he was a Consulting Physician. The “Consulting” title was accurate at the time. Mount Sinai's early staff usually consisted of four Consulting Physicians who visited the Hospital as needed or as they saw fit and as their active private practices allowed. The first staff of Consultant Physicians was Benjamin McCready, Chandler Gilman, William H. Maxwell, and William Detmold, an orthopedic surgeon in this prespecialty era. These men all had established reputations in the medical community, and their appointments augured great things for the young hospital.

The day-to-day medical affairs of the Jews' Hospital, as Mount Sinai was originally called, were run by the Resident and Attending Physician, Mark Blumenthal, and then by his successor, Seligman Teller. Blumenthal was the official doctor for the Portuguese Congregation and had an active practice. As Resident Physician, he kept office hours to see patients who were applying for admission to the Hospital and was responsible for overseeing their care while they were in the Hospital. For these efforts, he was paid $250 the first year, a sum that later increased to $500. Teller, who served for twelve years, eventually received only $400 each year, but the Hospital found him an apartment nearby and helped pay the rent. He also maintained an active general practice on the side.

The Hospital had forty-five beds when it opened in 1855. The rules governing admission stated that all patients should be of the Jewish faith, with the exception of accident victims, and it was decided early on to exclude those with incurable, malignant, or contagious diseases. This rule was rather loosely interpreted, with the medical staff arguing persuasively that if typhoid cases could be segregated, the patients could be relieved of suffering while posing little danger to other patients. It was also a continuing source of dismay to the doctors and Directors that a number of chronic patients found their way to Mount Sinai's beds. The Directors urged the Jewish community leadership for many years to open a chronic care pavilion. This situation was alleviated by the creation of the Montefiore Home in 1884.

In 1872, the Hospital, cramped in its small quarters on 28th Street, moved to a larger space on Lexington Avenue, between 66th and 67th streets. The new Hospital had 120 beds when it opened and eventually grew to 200. The beds were divided solely by male and female; there was no separation of medical and surgical patients until five years later. The move to 67th Street precipitated two major changes for the medical staff. The first was the creation of a formal Medical Board to oversee “all matters appertaining to the Medical Management of the Hospital.”1 The second innovation was the creation of a house staff system. With the move to larger quarters, it was believed that two young physicians would be needed to live in and help the Resident Physician to oversee the 120 beds. Appointment to the House Staff would be by competitive examination, and the new Medical Board took it upon itself to test the applying physicians and to recommend appointments to the Directors for the House Staff positions.

This House Staff plan was changed in 1877 to conform to the newly divided Medical and Surgical services. After this time there were four positions: Resident Senior and Junior Physician and Resident Senior and Junior Surgeon. (The “Resident” was later changed to “House.”) Again, those applying for these positions were vetted by the Consulting staff, initially through an oral exam and then through oral and written tests. These were “mixed” two-year internships; the doctors spent time on both services as Juniors and finished with a year as Senior on the selected service. They were years of intense learning; the resident oversaw all the patients, performed rudimentary tests, and aided accident victims. It was also a time when a tennis game on the court behind the Hospital could be interrupted by the sound of a steam whistle or (later) a gong announcing the arrival of an Attending. Since the tennis court could be accessed only from a window at the back of one of the wards, it could get exciting.

The Attendings on the medical service who served the Hospital on Lexington Avenue were a distinguished group. They included Alfred Loomis, Alfred Meyer, Edward G. Janeway, Julius Rudisch, and H. Newton Heineman. These men were important for their encouragement and support of the concepts that led Mount Sinai into the forefront of American medicine in the early twentieth century: the recognition of the role of the hospital as a teaching institution and of research as an important adjunct to hospital work. This included Meyer's creation of a library at the Hospital in 18832 and the efforts of many to convince the Directors of the value and need for a laboratory.

Several Mount Sinai physicians, especially the younger ones, traveled to Germany and studied the role of the laboratory, particularly pathology, in clinical medicine. Rudisch was trained in Germany and early on realized the potential of applying new laboratory techniques in chemistry and pathology to medicine. His interest was in diabetes, and he did later work in the medical applications of physics and electricity. He spent his retirement years studying chemistry.3

In 1893, the first rudimentary laboratory was established at Mount Sinai in a former cloak closet. H. Newton Heineman, M.D., paid for this laboratory. He also covered the salary of an assistant, making the fortuitous choice of Frederick Mandlebaum, who would lead the laboratories for the next quarter century. Heineman arranged and paid for Mandlebaum's training in Europe. In 1896, when Heineman retired to live abroad, Mandlebaum was made chief of the Pathology Laboratory.4

Another Attending of note was Edward Gameliel Janeway, “the greatest diagnostician of his day,” according to Emanuel Libman.5 A graduate of Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), Class of 1864, Janeway became a professor of Pathological Anatomy at Bellevue Medical College and later served as the school's Dean. He was a Health Commissioner of New York and took a special interest in tuberculosis. Heineman, Mandlebaum, and Janeway, among others, helped establish at Mount Sinai the value of a laboratory, not only to support the clinical work of the hospital but also to add to the base of scientific knowledge and to provide better training to young physicians.

The years on Lexington Avenue were a transitional time for Mount Sinai, as it was transformed from the care-taking facility of the mid-1800s into what is considered a modern hospital, with laboratories and specialized services. One of the components formed during these years was an Out-Patient Department (OPD). The work of the Hospital had always included taking care of accident victims, but the Hospital had long wanted to serve patients who required medical care but not hospitalization. This became increasingly important because the Hospital, no matter how many beds it contained, was never able to meet the demands on its services. By 1875, an Out-Patient Department was fully functioning, with an Internal (Medical) clinic. A separate staff ran the OPD at that time, with no oversight from the inpatient Attendings. In the 1920s, this changed, and one Chief of Service was put over both the inpatient and the outpatient staffs.

In 1893, the Hospital reorganized the medical staff to handle the ever-increasing volume of patients. A new category was created, the Assistant Attendings, later known as Adjuncts. On the Medical Service, the first two Assistants were Nathan Brill and Morris Manges.

Nathan Brill was born in 1860 and educated in New York, at City College. He interned at Bellevue Hospital, studied in France, and then worked on comparative anatomy and congenital defects of the nervous system. He learned his clinical medicine from E. G. Janeway. Brill was named Attending in 1898, serving until 1913. In his ward rounds he was quiet, serious, considerate, and unassuming. He was an authoritative master of diagnosis, renowned for scrupulous honesty and for defending truth. Brill's accomplishments were many. He defined endemic typhus (Brill's disease), coined the term Gaucher's disease (with Mandlebaum) and recognized it as a lipid storage disease, and described a form of lymphoma that became known as Brill-Symmer's disease.6

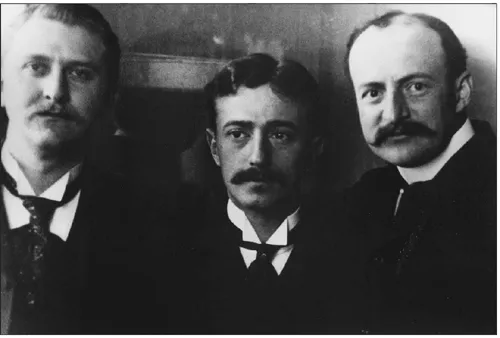

Charles Schultz, M.D., Charles Elsberg, M.D., and Nathan Brill, M.D.

Morris Manges became a full Attending in 1898. Manges was also a product of City College and received his M.D. from P&S. He studied in Berlin and Vienna and joined the Mount Sinai staff in 1892. A prominent consultant, Manges had appointments at various medical schools in New York City. Like other Mount Sinai physicians during these years, Manges had a wide range of interests and talents but was considered to be primarily a gastroenterologist.7 He was an artist and a collector. He was a member of the American Climatological Association, the New York Pathological Society, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the Archeological Institute of America. He was also a fellow of The New York Academy of Medicine, to which he donated the first specimen of radium to be brought to the United States. A patient of his had acquired this specimen at his advice in 1902. The treatment failed, but the widow gave Manges the radium, who, in turn, gave it to the Academy.8

In 1904, Mount Sinai moved to its current home on 100th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues. At the time, the Medical Service was in the hands of four men: Alfred Meyer, Julius Rudisch, Nathan Brill, and Morris Manges. With the much larger facilities at 100th Street, the House Staff was enlarged to four physicians in each year of the two-and-one-half-year program. By 1908, a separate Resident in Medicine was appointed to care for the Private Pavilion patients.

In 1905, a series of important meetings took place at Mount Sinai. One of the leaders in medicine, Sir William Osler, then at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, was brought in to give a clinical conference at the Hospital. While he was visiting at Mount Sinai, the Trustees took the opportunity to speak with him about the role of medical education and research at a hospital such as Mount Sinai, laying the groundwork for the changes that would occur over the next decade. These included the expansion of the laboratories, the beginning of dedicated research and education funds to send young doctors abroad for training, the admission of medical students on the wards for clinical training, and the establishment of a formal postgraduate training program. Osler came to Mount Sinai in part because of his friendship with a Mount Sinai physician, Emanuel Libman.

Libman (1872–1946) interned at The Mount Sinai Hospital and studied in Vienna, Berlin, Munich, and Graz. He had plans to become a pediatrician but became excited by research while in Theodor von Escherich's laboratory in Graz, where he discovered the Libman Streptococcus.9 Upon his return to Mount Sinai, he accepted an appointment as Assistant and then Associate Pathologist under Mandlebaum. His devotion to routine autopsies made him an unparalleled authority on clinical disease and helped give Mount Sinai a national and then international reputation. He started the bacteriology laboratory and pioneered in the early uses of blood cultures.10 In 1903, Libman received an appointment in the Department of Medicine. His brilliance as a rapid diagnostician was modeled on Janeway's powerful memory and an “I have seen this before” attitude. Libman was a leader in the study of subacute bacterial endocarditis, including naming the entity on the basis of extensive casework. Noting that some lesions were bacteria-free, he described with Benjamin Sacks atypical verrucous endocarditis, which, with or without lupus erythmatosus skin lesions, now bears their joint eponym as Libman-Sacks endocarditis. In addition to these observations, his association of coronary artery thrombosis and its clinical presentations entitled him to be termed the founder of the “Mount Sinai School of Cardiology” by William Welch, another leader of American medicine at this time.11

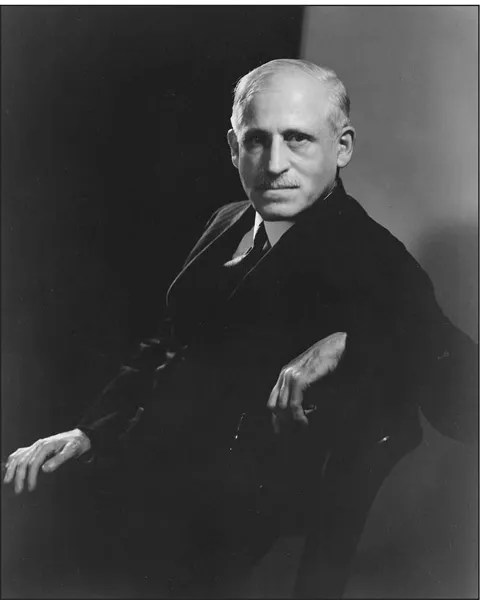

Emanuel Libman, M.D., Chief of a Medical Service, 1914–1925.

Libman was an early advocate of continuous medical education both at Mount Sinai and at The New York Academy of Medicine, and he gave or raised funds for several lectureships and traveling fellowships. He worked to save and find jobs for refugee doctors from Europe during the 1930s. He was an historian and rediscovered Thomas Hodgkin's grave in Jaffa; he also helped found the medical college at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Libman was in the first rank of both laboratory and clinical medicine, noted for his intellect and indefatigability. He was a loner with few social interactions but a distinct public persona. He was the only Mount Sinai physician to appear on the cover of Time magazine and to be profiled in both The New Yorker and The Reader's Digest, and his actions and interactions helped cement Mount Sinai's reputation at the highest rank.12

By the end of the 1920s, the Medical Services had assumed a more modern form. The inpatient and outpatient areas had been combined under one Chief, and the two staffs had begun to merge, although they never reached the level of integration desired. The Department had an active teaching program. The House Staff program continued to be very competitive and to provide excellent training to young doctors interested in both clinical and research work. Regular clinical-pathological conferences (CPCs) were held on Friday afternoons, filling the auditorium with both clinicians from the Hospital and members of the community. Undergraduate students from the New York University School of Medicine (NYU) and P&S received clinical training on the wards....