![]() PART 1

PART 1

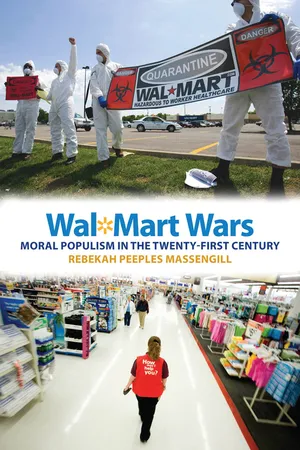

Why Should We Care about the Wal-Mart Debate?![]()

1

Constructing Moral Markets

Today, we’re the focus of one of the most organized, most sophisticated, most expensive corporate campaigns ever launched against a single company. For whatever reasons, our success has generated a lot of fear in some circles.

—Former Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott, Wal-Mart shareholders meeting, June 2005

Despite what its title might suggest, this is not really a book about Wal-Mart. Curiosity about the world’s largest retailer has prompted a spate of recent books about the company’s business model, history, and influence on the world’s economy—all worthy topics, to be sure. But as a sociologist, I am less concerned with what Wal-Mart does and more with what Wal-Mart represents. As a beacon of capitalism in a global marketplace, Wal-Mart invites both praise and condemnation from entrepreneurs, shoppers, and cultural critics alike—judgments that tell us more about what we value as a society than what we might value about any particular corporation. When considered as an icon of economic power, Wal-Mart is but one of a host of economic symbols that attract enough attention—indeed, much of it negative—to be a worthy object of investigation in its own right. This book might have been written about other public examples of controversial economic policy—such as whether immigrants should be allowed to receive public health services, or the Tea Party movement’s objections to the current tax code. Although all these controversies raise difficult questions about budgets, taxpayers, and the sanctity of market freedom, the central premise of this book is that such economic dilemmas are not really about the policy-specific details of dollars and cents, taxes or deficits. Instead, this book argues that beneath the surface of public talk about markets lies a rich moral vocabulary that Americans reference to evaluate these moral dilemmas of modern capitalism. Yet, although many of the moral concepts that constitute market processes draw on shared cultural symbols—for instance, the values of freedom, thrift, and individualism—the ways we discuss these values with regard to market society is also subject to political and moral struggle. The central goal of this book is to understand that contested process.

The public struggle to moralize the market is an ongoing project with a rich history in American political life. The availability of socially responsible investments and the recent proliferation of “fair trade” products are only a few of the ways that present-day markets represent avenues for moral behavior and social protest. Although such activities have a long and well-established history in American public life, debates about the merits of market logic seem perpetual because the solutions that best serve society’s interests and moral purposes are almost never clear-cut. Further, periodic episodes of social dislocation and rapid change often prompt a reevaluation of the market, its rules, and its institutions. For instance, a century ago the development of chain stores incited the ire of progressive activists who worried that this new form of market organization would threaten small town merchants and, by extension, central values of American life.1 In a progressive era where the sacrosanct rights of “the consumer” had yet to become established, this opposition attracted its share of supporters, including Huey Long and legislators in nineteen states that had levied hefty taxes on chain stores by 1939.2 The controversy that surrounded chain store merchandizing in the early twentieth century reminds us that the issues raised by the growth of stores like Wal-Mart are echoes of older, long-standing conversations regarding the well-being of consumers, the appropriateness of state power in limiting free markets, and the role of businesses in improving quality of life for larger communities.3 Such historical anecdotes also convey just how fluid the categories of “moral” and “ethical” are, both in actual practice and when considered over time.

Even though this book is not about Wal-Mart, this book is about the recent national debate over Wal-Mart—the pivotal two-year period of 2005–2006, and the hard-won concessions that Wal-Mart offered to its critics, especially the union-funded group Wal-Mart Watch. As such, it investigates only a slice in time, and the public discourse surrounding only one company. But by focusing on the deeper, perennial themes raised by activists on both sides of these issues, this book explores the process by which social movements attempt to offer a moral critique of the darker sides of capitalism, while also analyzing how these critiques fare in the public sphere. The global financial crisis notwithstanding, concerns about capitalism endure even in times of plenty, when credit is easy to come by and “market bubbles” seem unthinkable. The debate about Wal-Mart (which continues even as of this writing) challenges us to think about larger questions addressing the relationship between morality and market processes, particularly as they affect a range of people and issues, including low-wage workers, the environment, small businesses, taxpayers, and the array of consumers that make up the American public. Even though critics of capitalism are sometimes quick to accuse the market of immorality, I begin with the premise that markets are actually highly normative institutions that create moral meanings through the words and actions of those who interact with them. In particular, my interest here is in the recurring, patterned ways that Americans articulate different visions of a moral market through the strategic use of language—what sociologists call “public discourse.”

In recent years, sociologists have become increasingly interested in showing us just how much of what we call “the market” is subject to this kind of social construction. Fourcade and Healy, for instance, describe economic systems of monetary exchange as “more or less conscious efforts to categorize, normalize, and naturalize behaviors and rules that are not natural in any way, whether in the name of economic principles (e.g., efficiency, productivity) or more social ones (e.g., justice, social responsibility).”4 In other words, key components of market systems, such as legal forms of exchange, market regulations, and even currency itself, aren’t fixed entities at all. Instead, people and societies use markets to negotiate moral meanings and obligations, and draw on these webs of significance to justify different kinds of market activities. In fact, we could think of the market as a dependent variable that takes on particular forms of meaning and significance based on the cultural context in which it is situated.5 A good example of what this might look like in actual practice appears in Weber’s classic argument about the Protestant ethic. Fueled by angst over their uncertain salvation, Weber argued, the Calvinists turned to material success as an indicator of their divine status, prompting the savings and reinvestment that created bourgeoning markets in western Europe. The marketplace was considered a moral symbol of divine salvation, and Calvinists saw capitalism and the workings of market society as a place to affirm their individual moral worth.

Other, more recent work demonstrates that human beings do indeed use economic life to create shared expressions of moral significance. As the leading champion of this view, Viviana Zelizer has illustrated this point through her analysis of the social norms and legal codes surrounding intimate relationships.6 Challenging the “hostile worlds” notion that the caring relationships of love and family need to be kept separate from the presumably rational, unbiased world of market processes, Zelizer demonstrates that both of these things intermingle in actual practice. As she observes of efforts to separate relational ties from economic transactions:

The surprising thing about such debates is their usual failure to recognize how regularly intimate social transactions coexist with monetary transactions: parents pay nannies or child-care workers to tend their children, adoptive parents pay money to obtain babies, divorced spouses pay or receive alimony and child support payments, and parents give their children allowances, subsidize their college educations, help them with their first mortgage, and offer them substantial bequests in their wills. Friends and relatives send gifts of money as wedding presents, and friends loan each other money.7

Moreover, Zelizer goes on to argue that not only do these worlds of money and intimacy intermingle in actual practice, economic activity actually signals the creation of certain kinds of intimate relationships, as when parents choose a paid caregiver for their child, or when one partner gives another an engagement ring. The power of these economic symbols comes from their moral significance in our culture: for instance, nannies are expected to be caring and loving toward the children in their care, and an engagement ring signals a promise to marry. Far from being hostile worlds, Zelizer argues that the framework of “connected lives” better captures how people negotiate moral meanings and economic transactions in everyday social life. In both words and deeds, language and practice, our view of the market is intimately tied up with moral significance.

Contested Moral Markets

On the one hand, many such moral dimensions of market transactions are shared across whole societies. Most Americans, for instance, would interpret the exchange of an engagement ring as indicating a couple’s mutual commitment to marry. We all draw on institutionally embedded meanings like these when we work to understand economic activity. When sociologists speak of culture as a “tool kit,”8 for instance, they acknowledge that different societies (and the individual members of them) have a set of cultural resources that they draw on to understand, negotiate, and respond to different social situations. For instance, when Americans hear that the U.S. government will be acquiring a majority share of General Motors in order to prevent the company from declaring bankruptcy, they could interpret the situation from a number of vantage points. From one perspective, such interventionist policies could be understood as patriotic acts serving American industry and workers—an interpretation that draws on American legacies of collective accomplishment, national pride, and the historical value of unions in American manufacturing. On the other hand, the federal government’s intervention in the looming failure of a privately owned company was interpreted by others as a misguided form of meddling in the workings of the free market. Here, themes of independence, self-reliance, and corporate responsibility could be used to frame this decision as one that indulged a company that had made poor decisions and manufactured inferior products. The point is not that one interpretation is right or that another is wrong, but that both kinds of interpretations are feasible in American politics. Moreover, both interpretations would draw on moral ideals that have long been circulating in American culture—for example, collectivity, independence, patriotism, freedom9—in order to justify the interpretation as morally grounded.

Yet, even when activists share a common political history and a common society, their normative views of the world are not always the same. In fact, in a situation such as the government bailout of General Motors, it’s precisely because both sets of moral justifications circulate in the public ideology that the decision to assist the struggling company was met with so much controversy. If reasons to support the bailout didn’t exist—such as the themes of patriotism or mutual aid—then the decision would have had little chance of even being considered an option by key progressive policy makers in the federal government. On the other hand, the fact that it was met with such opposition from conservatives only underscores how economic dilemmas such as this one resonate with deeper, contested moral values that shape political debates about economic policy. Recognizing the fluid nature of moral debates helps to demonstrate how even aspects of the economic system that seem immutable—such as our abiding endorsement of “free” markets—are actually the result of social construction. Through the repeated interactions of people, institutions, and normative codes, key aspects of our social worlds are taken for granted, masking the degree to which these central features of social life are actually created by human beings themselves.

Morality is a uniquely powerful form of social construction, in that morality is concerned with what should be, and proposes a vision of the world that is ordered according to certain principles that are themselves the product of a particular social order.10 Put another way, morality “is concerned with broader questions about the modes of reasoning and talking that define things as legitimate,”11 and the sociology of morality seeks to analyze how different societies establish common values that grow out of their own history and culture.12 When activists put forward moral arguments about a political issue, for instance, they present an ordered vision of how the world ought to be (e.g., terrorists should not have the same rights to due process as citizens), and invite onlookers to consider the merits of their respective arguments (e.g., detaining suspected terrorists indefinitely does not violate their constitutional rights). An infinite number of moral arguments such as these—both those that are overt as well as more subtle varieties—are a perpetual part of the social order that constitutes our common political life.

The tricky thing about moral arguments, however, is that a growing body of research suggests that the intuitions that shape our moral frameworks are just that—intuitions, rather than the result of conscious, deliberate thought processes structured by logic and reason.13 The cognitive linguist George Lakoff argues this very point when he posits that Americans don’t think rationally when they evaluate political issues, but instead understand the nation primarily through two competing metaphors for the nuclear family: the conservative framework of a “Strict Father,” and the progressive vision of a “Nurturant Parent.” In the former, people see the world as a dangerous place in which individuals must learn self-reliance and discipline in order to be safe—thus Republicans tend to dislike expansive collective entitlement programs and support individuals’ rights to carry firearms. Progressives, on the other hand, prioritize nurture through collective care and empathy, supporting welfare programs and opposing capital punishment. At the same time, we are often unaware of how these moral metaphors affect how we actually think and talk about political issues in American life. Thus Lakoff argues that most Americans aren’t aware that they are guided by these moral metaphors for the family when they form political opinions—instead, most people prioritize one model over the other because it feels right at a deeper, intuitive level.14

If political discourse is indeed founded on moral metaphors that often escape our conscious recognition, it’s no surprise that most observers of American culture find our political discourse increasingly noisy and conflicted, with little promise for meaningful, lasting resolution. Even though most survey research shows that Americans aren’t nearly as divided on “culture war” issues as the media might suggest,15 most scholars agree that the elites and social movement organizations that increasingly dominate national media outlets have become more polarized.16 In fact, the perception that elites’ and political actors’ discourse has itself become more strident has been suggested by scholars as one reason why many Americans—academics and the lay public alike—have been so quick to accept this appearance of division as representative of the American public at large. When elites control the issues discussed, set proposed agendas, package candidates, and craft “talking points” that are reiterated across multiple forms of media, voters’ choices become increasingly circumscribed.17

What is the consequence of this polarized public sphere for the American people, and what difference does polarized market discourse make for our political culture? In th...