![]()

1

From City of Hills to City of Vision

The History of Yonkers, New York

No place feels quite like Yonkers, rough-hewn and jagged, a working-class bridge between the towers of Manhattan to the south, and the pampered hills of Westchester County to the north. . . . In sum, there is a defiant nostalgia here, the hallmark of a place that used to be something else, and that, too, is apt. During an era that no one still living actually remembers, but everyone seems to yearn for, Yonkers was a great city.

Lisa Belkin, New York Times reporter, 1991

In 1969, after two weeks of public hearings, a New York State Commission of Investigation discovered a private carting deal with Mafia leaders that cost the city of Yonkers approximately $1 million a year. When asked for his reaction, the Yonkers Chamber of Commerce president shrugged off the charges by stating, “All cities have their scandals.” In his report, Paul J. Curran, the commission’s chairman, admonished the city for being plagued with “intimidation, servility, favoritism, mismanagement, inefficiency and waste.”1 This incident might very well be the basis for the familiar Yonkers epithet, “a city of hills where nothing is on the level.” Though this characterization clearly is meant to disparage Yonkers, the city’s hilly geography is a suitable metaphor for understanding its complicated history.

Advancements in steamboat and railroad technology and the subsequent growth in business and population marked Yonkers’s ascent from small agricultural community to the “City of Gracious Living” by the end of the nineteenth century. Despite an influx of new residents and housing spurts in suburban tracts of north and east Yonkers during the 1920s and 1950s, the staggering loss of industry and jobs in the decades after World War II deeply wounded the city. These trends, coupled with a bitter battle during the 1980s over the desegregation of its public schools and housing, sent the Yonkers into a downward spiral from which it has only begun to recover. In 2004, the city unveiled one of the largest redevelopment programs in the New York metropolitan area, a $3.1 billion agreement in projected improvements that include a minor-league baseball stadium, retail and office space, and luxury waterfront housing. These projects, coupled with the new appellation “City of Vision,” suggest that Yonkers is not only on the mend but also on the rise.2

Heeding the call of “new suburban” historians such as Kevin Kruse and Thomas Sugrue, this chapter is attentive to Yonkers’s relationship with other communities in Westchester County, as well as its longstanding competition for new business and investment with neighboring New York City. These exchanges have been waged at the cost of accentuating class and increasingly racial inequality.3 To this end, this chapter narrates several episodes of economic pursuit that shaped the city’s history: unfettered industrial growth in the nineteenth century and the concomitant loss of manufacturing in the decades after World War II, federal and local housing policy, as well as the ugly desegregation controversy waged during the 1980s, in the name of protecting property value, that nearly emptied the city’s coffers. Together these periods reveal a long history of indifference in Yonkers to members of its working class. The city of Yonkers is hardly alone in its quest for economic development, but because it is smaller than New York City, and less politically powerful than its wealthier and influential suburban neighbors in Westchester County, the costs borne by its residents are more acute. As I relate events that accentuate inequality, I place the Yonkers Irish within that contentious history (although each cohort will be discussed at greater length in the chapters that follow). At the same time, I seek to contextualize the marked arrival of working-class Irish immigrants in Yonkers during the early 1990s as the city’s plans for redevelopment began to accelerate.

Becoming the City of Gracious Living

In 1609, when his Half Moon sailed along the river that later would be named after him, Henry Hudson stopped at the site of what is now southwest Yonkers and encountered a Native American settlement of Rechgawawanck Indians. The area was called “Nappeckamack,” or “trap fishing place,” because of the plentiful fishing offered by the nearby Nepperhan (later Saw Mill) River. The bay provided fresh water and a safe dock for canoes, and the village itself was located on high ground, making the vicinity safe from attacks launched from the nearby Hudson River.4 After receiving a grant from the Dutch West India Company, a young lawyer named Adriaen Van Der Donck purchased the land from Chief Tacharew in 1646. Shortly thereafter, he built a plantation and sawmill on the banks of the Nepperhan. Despite an untimely death in 1655, the area still bears his name. Called “de jonkheer,” or young gentleman, “De Jonkheer’s Landt” evolved into what we now call Yonkers.5

Frederick Philipse, who purchased much of Van Der Donck’s land in 1672, is thought to be the real founder of Yonkers. His sprawling estate, which became the Manor of Philipsborough by royal charter in 1693, remained in his family for more than a hundred years. Philipse’s home, Manor Hall, was built in 1682 and still stands. The U.S. government later confiscated surrounding property because his descendants had been loyal to the British during the American Revolution. Much of the land was sold to former tenants, who made a livelihood from the local farming of apples, peaches, and cucumbers, the latter earning Yonkers the nickname of “pickle port.”6 In addition, abundant waterpower offered by the confluence of the Hudson and Saw Mill Rivers made possible the cultivation of rye, wheat, corn, and oats. At the same time that fresh produce was being shipped out of Yonkers, many people passed through the small community by way of the stagecoach that began to travel between New York City and Albany in 1785. Here letters and mail were dropped off, horses were changed, and weary travelers found refreshment at the Indian Queen, where vegetables from the keeper’s garden supplied the food for simple, wholesome meals. Despite being an important rest stop, this village of little more than 1,100 remained primarily a community of small shops, mills, taverns, and farms into the early decades of the nineteenth century.7

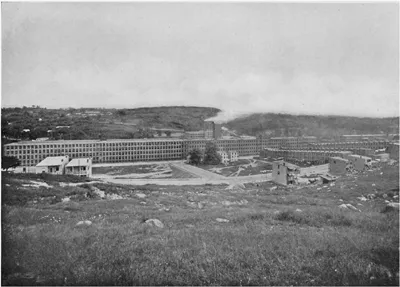

Steamboats and railroads changed Yonkers in the years that followed as reliable transportation facilitated the growth of New York City’s periphery. One contemporary noted in 1855 that suburban enclaves were “springing up like mushrooms. . . in Yonkers and other places on the Hudson River.”8 Five steamboat liners were stopping daily in Yonkers en route from New York to Albany by 1840. The completion of the Hudson River Railroad in 1849 brought trains into Yonkers three times a day. As a result, the village of Yonkers grew from 1,365 in 1810 to 11,484 by 1860.9 The increased connectivity with surrounding areas, coupled with the availability of waterpower, brought a new cohort of industrialists to Yonkers who sought an alternative to growing land and labor costs in nearby New York City. Some in Yonkers not only welcomed, but felt entitled to, this development. One local booster declared, “We are reasserting our right, as the natural suburb of NYC, and as the most beautiful residential property of the world, to a large share of the outgrowth of the city.”10 Yonkers soon became home to the refining of sugar and the manufacture of silk and furniture. The city’s better-known industrial wares included Alexander Smith’s carpets, Elisha Graves Otis’s elevators, Habirshaw’s cable and wire, and John T. Waring’s hats.

The small farming village of 1,300 grew into a city of 47,931, employing 8,615 people in 387 industries over the course of a century.11 Yonkers’s promise of a “better” business climate than neighboring New York City, which meant little or no government interference and a largely unorganized labor force, spurred part of this change. This environment may have been better for industrialists, but laissez-faire did not benefit all Yonkers residents, especially its working class. The Saw Mill River, previously dammed to produce mill ponds and harness maximum water-power, had become so polluted by the turn of the century that Mayor James Weller first ordered the destruction of their ponds. The water was redirected to an underground flume beginning in 1892.12 Those who labored in the factories and mills often lived in substandard cold-water tenements in and around Getty Square.

With some of the oldest housing stock in the city, southwest Yonkers had its neighborhood charm. The proximity of homes and the abundance of small stores and pedestrian traffic in Getty Square created a close-knit feel, prompting many residents to refer to this area as “the village.”13 The sound of clanging trolleys in the distance added to the hum of busy streets filled with shoppers stopping to chat with neighbors and friends while children fished off the nearby piers. Notable in this working-class landscape was the presence of bars, where men could fill their pails with beer on their way to and from work in the city’s many factories. Or perhaps they might sit a spell in the aptly named local watering hole, the Port of Missing Men. That Yonkers residents liked to drink was much to the chagrin of local resident William Anderson, state superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League. Yonkers voted overwhelmingly against Prohibition during a statewide referendum in 1926, and a discovery four years later revealed the city’s willingness to defy federal law. The Public Works Department found a four-inch hose that ran underground from a brewery that was supposed to be concocting “near beer” to a garage. Real beer actually had been traveling through the hose en route to distributors. New York University’s H. H. Sheldon commented that the public construction of such a line would have been an outstanding engineering feat, but its successful creation in secret was nothing short of extraordinary.14

Figure 1.1. The Moquette mills at Smith Carpet, 1904. Courtesy of Yonkers Riverfront Library, Local History Collection.

Racial and ethnic divides, nonetheless, punctuated working-class life in the city. More than half of Yonkers’s residents in 1900 were foreign-born or the children of immigrants. Beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, first the Irish and later Italians, Poles, Hungarians, and Slavs toiled in the factories and mills. A small African American community labored in lesser-paying foundry work or service-oriented jobs.15 An equally segmented housing market paralleled Yonkers’s stratified labor market as the city’s ethnic and racial groups lived in their own enclaves in and around Getty Square. Despite these constraints, minorities pioneered many firsts for the city. In 1905, John Alexander Morgan was the first African American physician to practice in Yonkers, and in 1925, Thomas Brooks became the city’s first African American police officer. Eastern European Jews, who left New York City’s Lower East Side for slightly larger, albeit cold-water, tenements, established Yonkers’s first permanent synagogue in 1887. Together these feats were firsts not only for Yonkers but for Westchester County at large.16

Yonkers’s wealthy industrialists, however, enjoyed greater economic and geographic mobility. They could afford to avail themselves of streetcar transportation and escape the increasing congestion and pollution of “the Square.” The Victorian homes and mansions that began to dot North Broadway housed the Smith, Otis, and Waring families. Northwest Yonkers, which contained successive heights of streets with Hudson River views, soon could boast of being home to mayors and state representatives, as well as William Gibbs McAdoo, former U.S. senator and secretary of the Treasury, and Samuel J. Tilden, Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in 1876. And in 1888, the city hosted the first round of golf played in the United States.17 The movement of the city’s elite from the southwest to the northwest quadrant marked the first wave of suburbanization in Yonkers. Not only did the city try to entice businesses seeking less expensive land and labor costs, but Yonkers also sought New York City’s wealthier residents, who were escaping the same problems associated with industrialization and urbanization that plagued Getty Square. A series of articles in the New York Times during the spring of 1894 touted Yonkers’s infrastructure, its “high standing” schools, nineteen railway stations, and “ample” supply of “pure water” but also its music hall, twenty-one churches, and an array of clubs that identified it as a “cosmopolitan” city. Two types of New Yorkers, the series maintained, could appreciate Yonkers, “Queen City of the Hudson”: the Wall Street man who enjoyed the “panoramic” commute to New York City, and the factory operator, drawn by conservative government, good police protection, and low taxes. The extension of the New York City subway system to bordering Woodlawn Heights in the Bronx after World War I, and the opening of the Bronx River Parkway in 1923, accelerated the suburbanization of Yonkers, especially in the city’s southeast region.18

Figure 1.2. Getty Square, Yonkers, New York, 1925. Courtesy of the Westchester County Archives.

An array of local boosters including politicians, newspaper editors, leading families, and real estate developers launched a campaign of civic promotion at the end of the nineteenth century. With the appellation “City of Gracious Living,” they sought to lure a wealthier demographic to Yonkers. Park Hill exemplified the type of development desired by the city. A community planned by the American Real Estate Company, Park Hill boasted of “fresh air, extra room for children and shady lawns,” of having “no foreign element,” and restrictions against saloons, shops, trolleys, and manufacturing establishments.19 The first homes were built in the early 1890s, although prospective residents could purchase lots and hire their own architects or charge the American Real Estate Company to oversee construction. In addition, the company could provide financing for any of these options. Early Park Hill residents had their own country club and could enjoy outdoor sports such as billiards and horseback riding. They did not, however, get to use the hotel, which a fire destroyed one month before its opening.20 Though Park Hill specifically lured many American-born upper-class residents from neighboring New York City, Yonkers more generally also attracted the upwardly mobile.

After World War I, working-class southern migrants and West Indian immigrants first settled Runyon Heights, which became one of the first middle-class Black suburbs in the metropolitan region. Perhaps capitalizing on the restraints Blacks faced in the housing market, both locally and in New York City, real estate advertisements in the Amsterdam News boasted of nearby churches, public schools, and a short trolley ride to subway trains. Because much of the better-paying manufacturing work in Yonkers was closed to people of color, Runyon Heights became a trolley suburb of commuters to New York City. One woman recalled, “Yonkers just wasn’t hiring black people, so you had to work in New York.”21 Runyon Heights, nevertheless, was an exception, as most working-class residents, both Black and white, lived within walking distance of local industry in the southwest. Residents of new suburban enclaves in northwest and southeast Yonkers usually were native-born middle-class whites. If anything, the city’s efforts to attract investment, whether in the form of new industry or wealthy residents, served to accentuate the class divides that already existed. Despite local boosterism, Yonkers was, according to the Works Progress Administration’s Guide to the Empire State, “on the east bank of the Hudson. . . a jumble of factories, mills and warehouses surrounded by the drab homes of workers [and] in attractive residential districts of eastern Yonkers [residents] have little to do with the industrial section to the west.”22

Postwar Challenges

On the heels of industrial and early suburban growth in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, the Great Depression brought hard times to Yonkers. On average, 40,000 Yonkers reside...