![]()

The jury system postulates a conscious duty of participation

in the machinery of justice.… One of its greatest benefits is

in the security it gives the people that they, as jurors actual

or possible, being part of the judicial system of the country

can prevent its arbitrary use or abuse.

—Chief Justice William Howard Taft

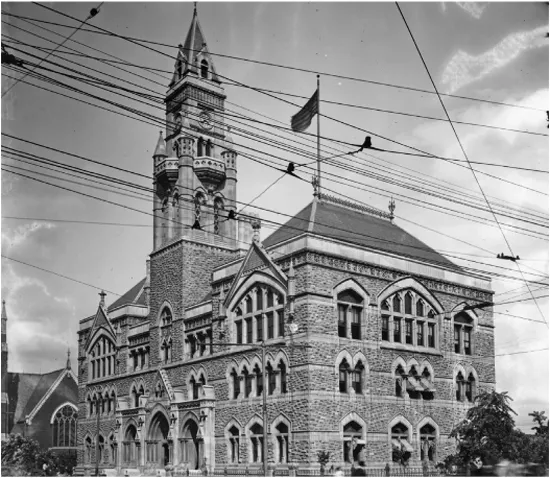

U.S. Courthouse (1900, 1938) Completed in 1882

SUPERVISING ARCHITECTS: William Appleton Potter and James G. Hill

Extension completed in 1938

SUPERVISING ARCHITECT OF EXTENSION: Louis A. Simon

The United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee met

here until 1952; the United States Circuit Court for the Middle District of

Tennessee met here until that court was abolished in 1912. Now owned by the city.

SOURCE: UNITED STATES TREASURY DEPARTMENT, A HISTORY OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS

(WASHINGTON, DC: GPO, 1901), 556–57.

1

An Invitation to Participation

A Summons

The letter arrives in the mail. “Dear Citizen” it begins.

You hold in your hand an invitation. Sure, it looks like an official jury summons, and it was probably not the invitation you were hoping to receive. Yet it is still an invitation—an invitation to participate in the American experiment of self-government.

It is not every day that we get an invitation saying “come join your extended neighborhood—meet the postal worker, cafeteria chef, banker, professor, or truck driver down the block.” It is not often that you are asked to socialize with a randomly selected group comprising all the types of people who live in your city or town. And you can feel flattered that you have been invited. It means that you have not committed a felony1 (that anyone knows about), that you are mature enough to judge others,2 and that your community needs you. Of course, it might be nicer if your “invitation” was gold-embossed with fancy lettering, rather than the dot-matrix copy that remains in some courthouses, but whatever the paper stock or font, it is an invitation that millions of Americans receive every year.3 And it’s only polite to accept.

As you ponder the conflicts that the jury date poses with your schedule—work deadlines, family vacations, day care, and the like—remember that you have been invited in a role independent of those responsibilities. You were invited because you are a citizen, not a mother, father, daughter, employee, boss, or unemployed actor. Nothing you have accomplished or failed to accomplish is relevant to your service. The summons requires you to consider yourself in a new role distinct from the identity you have spent your life creating. The famous and not famous appear before the court in the same position. Even judges when called to jury duty in their own courthouses have no more power than does the ordinary layperson. You are simply a citizen—a citizen with an important responsibility.

That responsibility is usually mixed with a bit of uncertainty. Uncertainty about the process. Uncertainty about the time commitment. Uncertainty about the expectations.4 This uncertainty is to be expected. There is an information imbalance in the irregular requirement of jury service. You have been asked to play a role in the justice system, but what role, for how long, and about what subject has not yet been decided. You might end up a jury foreperson in a scandalous civil trial, or an alternate in a petty criminal case, or never selected after hours of waiting in the jurors’ lounge. While uncertainty abounds, it is a responsibility that requires your physical presence. You have to get up, head to the courthouse, and see what happens.

A jury summons is an invitation to participation. Jurors are asked to involve themselves in some of the most personal, sensational, and terrifying events in a community. It is real life, usually real tragedy, played out in court. Jurors confront disturbing facts, bloody images, or heart-wrenching testimony.5 There is no way to hide when one is shown the blown-up, blue-tinged autopsy photograph of a dead man, or the results of some horrible accident involving a defective product. A jury may have to decide whether a man lives or dies, or whether a multimillion-dollar company goes bankrupt. A jury will have to pass judgment in a way that will have real-world effects on the parties before the court.

Of course, before you get to the heightened emotion of trial, your participation may feel more like a trip to the local Department of Motor Vehicles—a lot of bureaucratic waiting, punctuated by seemingly inefficient systems for organizing the mass of people who arrive each day. Actually, it’s a pretty efficient process in most courthouses, but for the uninitiated, it might not seem that way.

As you wait, look around the jurors’ lounge and observe the diversity of your fellow citizens. Almost every shape, form, and type of American sits around you. Some sit around discomforted by the waiting and frustration. Others seem to be looking forward to the opportunity to stay and serve. People are reading history books and comic books, people are knitting sweaters and writing computer code, people from all walks of life sit together, expecting to become a part of something (or hoping to avoid it).

Of course, whether viewed positively or negatively, your jury summons is not optional. You can’t respectfully decline attendance at this year’s criminal or civil trial. In some jurisdictions, United States Marshals are sent to haul jury duty scofflaws into court to face contempt proceedings.6 Both the skipping of jury service and the punishment are ancient traditions. In colonial Virginia, absent jurors were fined in pounds of tobacco for their failure to attend as requested.7 Today, you might be looking at a $500 penalty.8

So, holding that summons skeptically, one question you might have is “why was I invited?” Odds are you are not a lawyer, constitutional scholar, or experienced judge, so why were you—unelected and untrained you—asked to participate in rendering judgment? As the esteemed Harvard Law School Dean Erwin Griswold commented, “Why should anyone think that 12 persons brought in from the street, selected in various ways, for their lack of general ability, should have any special capacity for deciding controversies between persons?”9 And while overly cynical, it is, in part, true. No one in the United States is trained to become a juror. There are no classes, no crash courses, no study aids.10 So why would you be asked to participate in something you have never been taught to do?

The answer goes to the heart of our constitutional system of government. The “We the People” that begins the Preamble to the Constitution means you:

We the People of the United States … do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.11

We established a system of government in which “we the people” are sovereign. And sovereigns have to govern. We require people to participate in a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”12 Popular sovereignty (meaning the voting booth you see once every two to four years) ensures that the power comes from you—not a king, not a religious figure, but you—the same person shaking your head at that jury summons. As Justice Louis Brandeis once famously stated, “The only title in our democracy superior to that of President is the title of citizen.”13 In practical terms, this means you are summoned to participate in jury duty because you are the source of constitutional power.

The Jury

The jury evolved over centuries of continental and British experimentation before reaching American shores.14 Yet the American jury during our Founding era was something quite unlike its forebears. Far more than merely a fact-finding body, colonial criminal juries acted as legal revolutionaries on occasion, defying British rule.

One of the great causes that captured the attention of the fledgling nation was the unfairness of the Stamp Act. You may remember from American history that the stamp taxes on tea and other goods became a symbolic rallying cry against British oppression, leading to the Boston Tea Party.15 Yet the concern was not simply the taxes, but the fact that violators of the Act were to be tried in admiralty courts without a jury.16 Colonial anger toward the Stamp Act included a jury demand. And it went further. Local criminal juries refused to enforce British customs laws17 and prevented convictions for seditious libel against the British Crown.18 Local civil juries even awarded damages for colonial smugglers caught circumventing British law.19 In short, juries became an instrument of the struggle that resulted in revolutionary demands at the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, the First Continental Congress in 1774, and ultimately the Declaration of Independence in 1776—a declaration that listed King George’s denial of “the benefit of trial by jury” as one of its justifications for independence and war.20 The Tea Party was not just about taxes, but also about juries.

At the same time, colonial juries did manage to maintain some of the participatory practices of traditional fact-finding bodies. One of the more celebrated criminal trials of the time involved eight British soldiers who were accused of murdering several Boston citizens in 1770.21 In what became known as the “Boston Massacre,” these foreign soldiers had been accused of shooting into a mob of angry colonists. Paul Revere rallied Boston into a frenzy of anger and resentment over the death of five men, including Crispus Attucks.22 The British were already despised in those prerevolutionary days, making a Boston jury a difficult forum for a fair trial. Yet the decision was made to keep the trial in Boston. As Akhil Amar wrote, “[P]atriots had insisted that fair trials could and should be held in Boston itself, in proceedings that would showcase both community rights and defendant rights, republican freedom and individual fairness.”23 Future President John Adams (then just a young lawyer) took the soldiers’ unpopular case. Suffering community opprobrium, Adams successfully argued that the soldiers had acted in self-defense against the angry mob, asserting, “Facts are stubborn things … and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictums of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”24 Asking the jury to consider how the soldiers should have acted facing the “rabble,” throwing “rubbish” and yelling “Kill them! Kill them!” Adams managed to convince his fellow Massachusetts citizen–jurors to acquit six out of the eight soldiers and get lesser charges for the other two.25 The exonerations gained an added legitimacy from the participation of the local community jury.26

From our perspective today, colonial juries, especially grand juries, were almost activist, exercising powers we would now consider properly handled by the other branches of government.27 Grand jurors today weigh evidence on individual suspects in individual cases presented by prosecutors. Colonial grand juries, however, went so far as to be tasked with inspecting roads, monitoring public expenditures, investigating public corruption, and overseeing pauper laws and prisons.28 In Virginia, courts relied on grand juries for advice on assessing taxes and the construction of public buildings.29 Early Massachusetts grand juries were free to investigate any abuse of governmental power or use of funds.30

As a model of citizen-based self-government (or at least the portion of white male “citizens”), the drafters of the Constitution could not have done better than to follow the successful practice of juries. Jury participation, like voting participation, was deemed the best way to protect citizens from a larger central government:31 “Just as suffrage ensures the people’s ultimate control in the legislative and executive branches, jury trial is meant to ensure their control in the judiciary.”32 By immersing jurors in the actual administration of justice, they would be empowered to protect fellow citizens.

But where does this idea of citizen participation come from? The answer is that it comes from the Constitution itself.

Participation and the Constitution

Your presence as a juror is but one example of the constitutional requirement that citizens engage in government. ...