![]()

1

Liberalization and Backlash in the Obama Era

There are some who question the scale of our ambitions, who suggest that our system cannot tolerate too many big plans. . . . What the cynics fail to understand is that the ground has shifted beneath them, that the stale political arguments that have consumed us for so long, no longer apply.

—President Barack Obama, January 2009 inaugural speech

The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.

—U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky), October 2010

When Barack Obama was elected president of the United States in November 2008, it was indeed a historic moment for a country that had fought a civil war almost 150 years before over issues that included the right of plantation owners to own African slaves as their property. Obama’s victory was impressive by several standards. Just four years after President George W. Bush’s political advisor Karl Rove had proclaimed that the 2004 Bush reelection demonstrated that America was a “center-right” country, and that those election results would insure many years of conservative and Republican rule, the country had turned instead to a different direction, in a remarkable manner. Though he prevailed by a popular vote of 53%-46%, Obama had won in the critical electoral vote by a much larger margin and had succeeded in states that had been out of the Democratic column for some time—such as Indiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. He had even prevailed in Florida, the site of the 2000 election dead heat between Bush and Democratic candidate and vice president Al Gore.

Barack Obama had achieved a greater percentage of the total vote than had any Democratic candidate since Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Democrats also won control of the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives, giving Obama an opportunity, at least in his first two years, to set an agenda and push for passage of significant legislation. To some, the Obama election represented more than the ascent of a progressive Democratic vision. To them, the newly elected president—who himself had famously emerged on the national scene with a 2004 Democratic convention speech that spoke of a “red America where we have gay friends, and a blue America where we worship an awesome God” (Washington Post 2004)—represented a sea change in another direction: the promise to be a post-partisan president who could move beyond the hyper-partisanship that had been characterizing American politics from the time of Richard Nixon and the Vietnam war. Soon after the 2008 American presidential election, some social scientists and political analysts concluded that the contours of the election and its outcome had signaled an end to the polarization and culture wars that had typified American politics for the prior three decades. To them, demographic changes would be forcing the demise of the culture wars, broadly defined. To others, the moderating of religious groups was having a similar effect. In both cases, it was thought that electoral defeat would have the effect of minimizing and defusing the contestation of the culture war issues—especially the long-standing “wedge issues” of religion, gay rights, and reproductive rights.

As social conservatives came to grips with the 2008 electoral defeats, there were those among them who argued the opposite. They emphasized the greater salience of culture war issues as a way of reviving their role and maintaining the thrust of those wars. To some, such a focus could be the seeds for the conservative movement’s “intellectual rebirth.” To those leaders, social conservative voices in the national debate “won’t be silenced.” This book provides an analysis and assessment of the meaning and implication of those changes. In particular, it chronicles the conservative resurgence of 2009 and 2010 and the midterm elections rolling back the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. It examines the successful—though never comfortable—Obama re-election in a very contested 2012 campaign.

In a previous work, Sin No More (Dombrink and Hillyard 2007), I had argued that, despite conservative rhetoric, the tide was turning on the core legal and moral issues of the American culture war, with all moving toward normalization in American society—but not always easily. Daniel Hillyard and I challenged the dominant interpretation of the 2004 election as showing a social conservative America, what Karl Rove has called a “center-right” country. In continuation, this book reports on research extending that analysis into the 2008–2014 period. This book poses the question, Which is the best explanation of the current trends in American society on issues related to political division? It concludes with the assertion that we are witnessing the decline of social conservatism as a vital force in the shaping of American political and social thought.

I present competing analyses. Is the best depiction of America on issues that the culture war celebrated, on which social and religious conservatives mobilized, one of growing toleration? Does the coming to maturity of the “millennial generation” of American youth predict a growing normalization and legalization of gay rights and same-sex marriage? Chapter 6 shows these values competing/colliding in the 2012 presidential election. Or is the portrait of contemporary America to be found in the anger and resentment and challenge to the Obama presidency represented by the “tea parties,” “birthers,” “deathers,” “Tenthers,” and the congressmen who yelled “You lie!” at the president during a speech in Congress and “Baby killer!” as a colleague announced that he would end his focus on pro-life issues and support the Obama healthcare plan in March 2010? Which is the near American future? Is the consistent theme the increasing moderation on some issues, as was argued in Sin No More? Or is today’s key story one of backlash and growing polarization? And is it possibly a combination of both?

Birthers, Deathers, Tenthers, and Tea Parties: Polarization and Hyper-partisanship

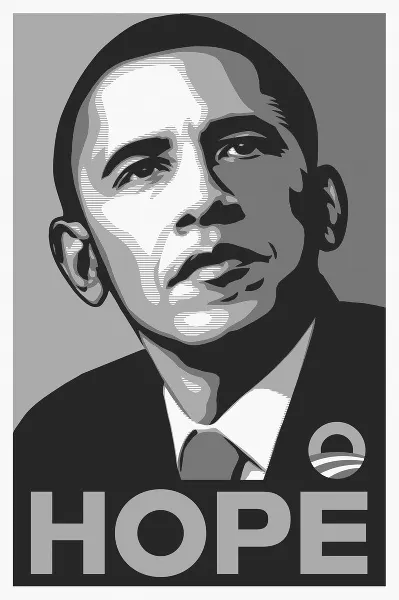

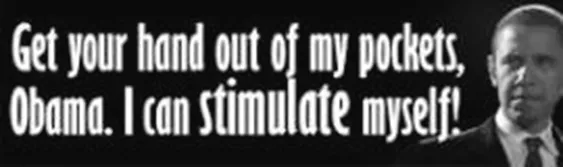

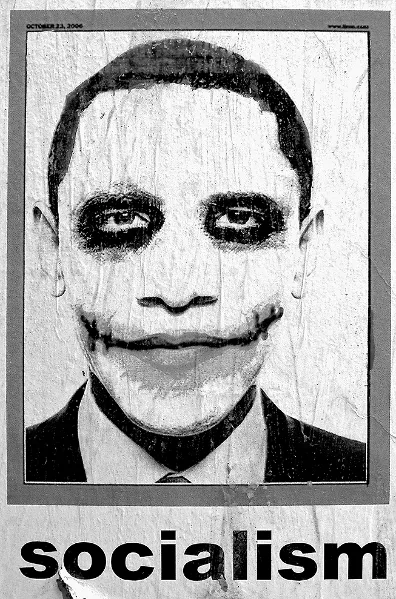

When one can easily find Internet images in 2009 onward of Barack Obama in the pose of Nikolai Lenin, or with a bust of Karl Marx in the Oval Office, or shown in the startling pose of Heath Ledger’s Joker character from The Dark Knight (Nolan 2008), or Photoshopped in a traditional racialized pose shining the shoes of Sarah Palin, or depicted as Adolf Hitler in “Dreams from My Führer”—a parody of Obama’s 1995 memoir, Dreams from My Father—it is difficult to remember that there was indeed a post-election “honeymoon period” for him, like those that most newly elected presidents enjoy. It is also hard to recollect that there was a parallel “wandering in the desert” moment for the Republican Party, which was torn between pragmatists and moderates and conservatives who felt that Senator John McCain had lost the presidential election in 2008 precisely because he did not represent the full-throated conservatism that the Reagan years had established as a growing force in American politics. Obama, who had been celebrated for bring a potential post-racial, post-partisan and post–Baby Boomer president, was soon on the road to a vilification that has been unique, given the era of the 24/7 news cycle and unprecedented social media.

During the building of the Obama backlash, the images of opposition were striking and severe: “Hey Barack, go stimulate yourself”; “Just another bum, looking for change”; “I’ll keep my faith, guns, freedom, and money . . . you keep the change”; “Dreams of my Führer” (with the image of Obama as Hitler); “Obama is what you get when you allow illegals, idiots, and welfare recipients to vote”; “Why so socialist?”; “Yes we will!” (with Obama in foreground and images of Marx, Lenin, and Mao in background); “Obama for President: because this time socialism is going to work” (with the image done in style of an Obama 2008 campaign sign).

These events had been taking place in the opposite direction of what several political analysts thought might take place (or hoped would occur). Peter Beinart had supported this line of analysis, writing soon after the 2008 election:

When it comes to culture, Obama doesn’t have a public agenda; he has a public anti-agenda. He wants to remove culture from the political debate. . . . Barack Obama was more successful than John Kerry in reaching out to moderate white evangelicals in part because he struck them as more authentically Christian. That’s the foundation on which Obama now seeks to build. (Beinart 2009)

At the same time Beinart was expressing hopes for a post-partisan Obama administration, some social conservatives like Gary Bauer (and eventually Rush Limbaugh) were exhorting their followers not to give in, not to compromise, and to draw a line in the sand for conservatism:

Within hours of Senator Barack Obama’s election, those on the Left, in the media and even some in our ranks began making demands for conservatives to cooperate with the new administration in the early months of his presidency. I reject those demands.

It won’t be easy, but more Americans still describe themselves as conservative than as liberal, and they are looking for leadership, not more sellouts. (Bauer 2008)

Bauer would later add:

It has again become fashionable to declare the end of the culture wars, the highly charged political debates about religion, abortion, homosexuality, race and related issues. But . . . the culture wars are as highly charged as ever. They will endure until the issues that provoked them are resolved. (Bauer 2009b)

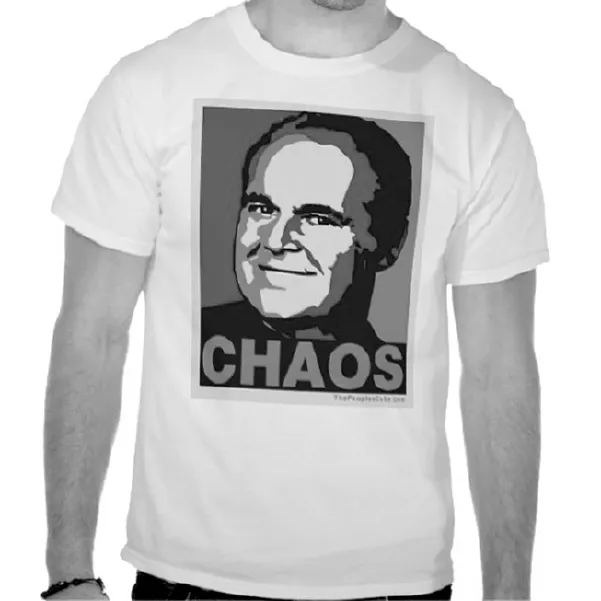

Soon after the Obama election, some progressive analysts were considering the “end of conservatism” and the twilight of Reaganism, the guiding philosophy of Republican candidates for almost 30 years. Rush Limbaugh exhorted conservative followers of his show and American conservatism to take up the fight and see resistance as the proper path to the rebirth of a conservative presence or dominance (Limbaugh 2009). In a notable February 2009 speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Limbaugh, delivering his “anti-state-of-the-union address” only one month after the Obama inauguration, was clear in his analysis: “Obama is dangerously wrong”:

President Obama is so busy trying to foment and create anger in a created atmosphere of crisis, he is so busy fueling the emotions of class envy that he’s forgotten it’s not his money that he’s spending. In fact, the money he’s spending is not ours. He’s spending wealth that has yet to be created. And that is not sustainable. It will not work.

On the left side when you get into this collectivism socialism stuff, these people on the left, the Democrats and liberals today claim that they are pained by the inequities and the inequalities in our society. And they believe that these inequities and inequalities descend from the selfishness and the greed of the achievers. And so they tell the people who are on different income quintiles, whatever lists, they say it’s not that you’re not working hard enough, you could have what they have, perhaps, if you applied it. They’re stealing it from you.

Spending a nation into generational debt is not an act of compassion. All politicians, including President Obama, are temporary stewards of this nation. It is not their task to remake the founding of this country. It is not their task to tear it apart and rebuild it in their image. (Limbaugh 2009)

“Hell no?” asked Rush Limbaugh in his August 14, 2010, broadcast. “Damn no! We’re the party of Damn no! We’re the party of ‘Hell No!’ We’re the party that’s going to save the United States of America!” (Bromwich 2010). Limbaugh had updated the claim of leading 1960s conservative William F. Buckley, who wrote that his National Review “stands athwart history, yelling Stop!” (Buckley 1955).

In arguing against the need for an inclusive “big tent” approach in launching a coalition that would bring the Republican Party back to power, former Arkansas governor, Southern Baptist minister, and 2008 Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee was clearly with Limbaugh: no big tents. Huckabee hinted at the purity required for a conservative resurgence: “However wrongheaded Democrats might be, they tell you exactly what they’re going to do. The real threat to the Republican Party is something we saw a lot of this past election cycle: libertarianism masked as conservatism.” (Huckabee 2008). This challenge to those who would propose a reduced emphasis on social conservative topics was direct.

Obama as Socialist

One common charge from the tea parties and Republican opponents was that President Obama had taken a decidedly socialist path to bringing the American economy back in the time of economic turmoil. A 2010 Harris Poll found that 67% of Republican respondents felt that Barack Obama was a socialist. This translated to 40% of the American public.

To the historian Rick Perlstein, these charges were similar to those that had confronted Democratic presidents promoting government as a response to economic concerns, including Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. In the context of this “genealogy,” he argued that the threat of the “enemy within” America was a common theme (Perlstein 2010). To another observer, “Tea party activists seem to live in information silos that reinforce their beliefs. To an alarming extent the frame of Obama bringing socialism to America include[s] allegations that Obama and his allies are part of a vast left-wing conspiracy” (Berlet 2009). To another:

Something very much like the tea party movement has fluoresced every time a Democrat wins the presidency, and the nature of the fluorescence always follows many of the same broad contours: a reverence for the Constitution, a supposedly spontaneous uprising of formerly non-political middle-class activists, a preoccupation with socialism and the expanding tyranny of big government, a bitterness toward an underclass viewed as unwilling to work, and a weakness for outlandish conspiracy theories. (Drum 2010)

The polarization and hyperpartisanship that had escalated in Washington, D.C. (and the nation) became vibrant in 2009 when the Obama administration proposed its healthcare reform proposal, and the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives and Senate began deliberations on a potentially radical restructuring of an important American concern.

Lone among its industrial counterparts, America had persisted without a government-funded national healthcare system and had promulgated a market-driven system that left as many as 44 million of its citizens without healthcare coverage. As had happened with the Clinton administration in 1993 (although its efforts did not succeed), the features of the Obama reform—creation of a risk pool for uninsured Americans, reduction in Medicare payments, abolishment of the role of preexisting conditions—was dwarfed by the perception that the reform was a “typical” Democratic “giveaway” program of fiscal support, albeit this time benefiting millions of Americans.

“Normal People Values”

In 2008, Republican congresswoman and conservative leader Michele Bachmann had said about Sarah Palin and her family, then under attack, that “they stan...