![]()

1

Supermodels of the World

Living the Life

Carolyn, a veteran model agent who had witnessed the profound transformation of the industry when models became “super,” called it a “total freak-out” for the business, saying:

It was ’83 – ’84, and I’m a model agent at Elite at this time. So I’m on a board, with all of these girls starting at exactly the same time. Five minutes ago, there was no Stephanie Seymour, no Cindy Crawford, none of these girls, and five minutes later they’re all there at the same time. It never happened again. Not in the last twenty years. That kind of sensationalism where all of these girls started to work at exactly the same time — it was mind-boggling, just a complete, total, freak-out to the business. The business was accustomed to maybe one or two girls of the moment. And now they’ve got like, ten girls of the moment who are trading off on Vogue covers and Bazaar covers, and Mademoiselle covers and working with Irving Penn, and working with Avedon, and it’s just a crazy time in the industry. And from there, this terminology, “supermodel” came up.

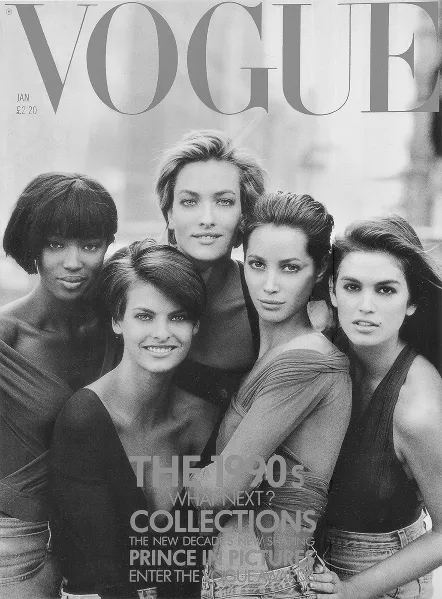

The “elite clique known as supermodels” included five or six women: Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington, Claudia Schiffer and, as NY Times journalist Alex Kuczynski once quipped, “depending on your mood, Kate Moss.”1 The modeling stars of the 1950s and 1960s may have been muses to famous fashion photographers, but supermodels in the 1980s and 1990s were celebrities in their own right.

After Linda, Christy, and Naomi started working consistently with the bad-boy photographer Steven Meisel, famous almost as much for his rabbit fur hats and kohl-lined eyes as for his photographs, they were soon known as “The Trinity. ” The three worked together, doing the fashion scene in Paris, London, New York, and Milan, telling People magazine in June 1990, “We’re an Oreo cookie in reverse. We’re only a third without each other.”2 In the space of a few short years, they had become so famous, bodyguards pushed them through the mobs of fans waiting for them outside of shows.3 They dated rock stars (Seymour had a volatile affair with Guns N’ Roses lead singer Axl Rose that ended in allegations of violence on both sides), prizefighters (Campbell dated Mike Tyson), associated with royalty (Schiffer was linked to Prince Albert of Monaco), and married movie stars (Crawford married Richard Gere in Las Vegas). Whole issues of the various Vogue magazines seemed devoted to them.4 They posed nude for Rolling Stone, appeared on celebrity television shows such as Entertainment Tonight and MTV news, and starred as themselves in a rock video, lip-synching the words to George Michael’s song “Freedom.”5 With the growing interest in models and modeling, and the growing paychecks, even some men got into the game. Although Marcus Schenkenberg and Mark Vanderloo garnered nowhere near as much attention or money, the frenzied interest in models and fashion made “supermodels” of them as well.

After their meteoric rise in the mid- to late 1980s, by the 1990s, the supermodels’ place in the celebrity pantheon was secure. Cindy Crawford’s Shape Your Body Workout video hit the shelves in 1992. In 1994, both Naomi Campbell’s novel about the industry, Swan, and Robert Altman’s film about the fashion world, Ready to Wear (Prêt-à-Porter), were released. Unzipped, designer Isaac Mizrahi’s documentary prominently featuring the supermodels, came to theaters less than a year later.6 The year 1996 immortalized models Karen Mulder, Naomi Campbell, and Claudia Schiffer as action figure dolls.7 A restaurant featuring celebrity models, the Fashion Café in New York City, temporarily became the epicenter of the public interest in supermodels.8 The year 1997 – 1998 could have been dubbed “The Year of the Model”: Supermodels Marcus Schenkenberg and Veronica Webb each published an autobiography,9 two well-known authors published novels about models: Model Behavior by Jay McInerney and Glamorama by Bret Easton Ellis, and a series of teen novels appeared sporting catchy titles like Model Flirt and Picture Me Famous.10 Cable shows like CNN’s Style series, hosted by Elsa Klench, Behind the Velvet Ropes, with Lauren Ezersky, and MTV’s House of Style, hosted by the supermodel Cindy Crawford, brought fashion and modeling into everyone’s living rooms. As Ezersky pointed out in a phone interview,

Before the 1980s, the collections were small. Once they [were] televised, they were seen by hundreds of people. The shows themselves got bigger, too. Now five hundred, eight hundred people might attend a show. In the 1970s, when it was smaller, people still cared about it, but there were fewer outlets. There used to be just a few pictures released after a fashion show, but it’s more accessible now.

Interest in fashion was so high by the end of the 1990s, network television took the plunge and produced two network shows, Veronica’s Closet, about a lingerie designer, and Just Shoot Me, a sitcom about a fashion magazine, which, at the time, represented a large portion of the primetime market.

The transition to fashion as entertainment made the lives of the supermodels fodder for the entertainment mill. Anything models did became worthy of exposure, from the fabulousness of walking the runway or going out on the party circuit, to the mundane rituals of shopping or going to get a facial. Models became household names, a turning point in the industry, key to organizing the development of glamour labor as a widespread practice. Nicholas, a fashion public relations (PR) agent, pointed out that

there’s a hunger for content because there are more outlets. The number of magazine titles in the past ten years has something like tripled. So you need more content, so you search for more subject matter. And in that search, the media writes about the lives of models, which I don’t think twenty years ago anyone would have given a damn about.

Only about twenty himself, Nicholas may be forgiven his ignorance of the models Dorian Leigh and her sister Suzy Parker’s famous exploits, chronicled in the gossip sheets of the 1940s and 1950s, the 1960s media’s complete captivation by all things Twiggy, or the New York Post’s and Daily News’s relentless coverage of Cheryl Tiegs’s marital woes in the 1970s.

Clearly, people did “give a damn” about models’ personal lives, but the number and importance of scandal or gossip items related to models in the past couldn’t compare to the explosive growth of media images of models and modeling in the 1980s and 1990s. The fashion historian Harriet Quick described how in this era, “Fashion entered every facet of life”:

Everything got bigger in the eighties. Fashion was fashionable; the elite sport blossomed into a global consumer industry. Designers licensed their names into perfume, accessories, chocolate, cosmetics. Brand names became so lucrative, Yves Saint Laurent was able to float his business on the stock market. Fashion entered every facet of life. Nothing was quite as grand or indeed pretentious as the biannual prêt a porter collections; broadcast through satellite and TV stations world-wide, the collections turned into a media spectacular. In 1986, the Paris shows were attended by 1,875 journalists and around 150 photographers: nearly a four-fold increase on the figures recorded for 1976. Front rows were studded with celebrities, backstage awash with champagne.11

The 1980s and 1990s saw huge leaps in modeling’s visibility, globalization, and profitability. In the proliferation of cameras backstage at runway shows and in media following models’ lives, documenting their antics, boyfriends, and tantrums in ever closer detail, fashion — the perfect filler for the newly created expanses of hundreds of channels — reached more audiences and began to infiltrate daily life. Fashion became entertainment, and models became superstars. Fashion’s elite circle increasingly entangled average consumers, drawing them into fashion’s rhythms.

The story of the supermodels is the story of fashion’s encroachment on the everyday, entraining publics to its whims. By the 1980s, fashion consolidated into global mega-brands, and cable and satellite technology sent carefully crafted, globally appealing images zipping around the globe. These new networks honed crude forms of branding and mass fashion, originating in the 1960s and 1970s, into a sophisticated machinery of appeal, enabling models to become “super” and laying the building blocks for glamour labor. The transition from selling products to selling brands profoundly changed the face of modeling, linking models, images, and consumers in novel ways. The regime of the blink refigured the world into publics willing to brand themselves and those unwilling or unable to do so, as the regularizing forces of the biopolitics of beauty became more firmly entrenched. During this seismic shift in the 1980s and 1990s, the supermodels were a “total freak-out” for the business, as my respondent Carolyn put it, because they didn’t just represent products, they lived the life of the luxury brands to which they lent their “look,” inhabiting that fantasy world so convincingly that we all started to believe.

Pierre Cardin Frying Pans

The transition to a world of designer kitchen appliances and brandscapes shaped by lifestyle-consumption choices has its roots in the early 1970s. As communication became a key element of production, the ability to do it well became highly prized. As the dominant Fordist mass production, distribution, and consumption structures fell into decline, post-Fordist structures of flexible labor and just-in-time production emerged.12 The 1970s transition to a post-industrial economy, combined with advertising’s efforts to reach “niche” markets, made signs and symbols, such as Pierre Cardin’s designer cachet, rather than product durability or performance, into important selling points. The question was less how something was made than who made it, a powerful draw for designers who slapped their names onto everything from blue jeans to frying pans.

The emerging preeminence of brands over products shook the fashion world to its roots. Models and designers played the branding game with consumers and the paparazzi at the Studio 54 nightclub, as the new cable and satellite technology inaugurated a veritable blitz of visual images that irrevocably changed the quality of everyday life, intensifying the competition for attention. While Twiggy was mobbed on her first visit to New York and Cheryl Tiegs and her compatriots often made headlines, their fame was qualitatively different from that of the supermodels. The supermodel moment emerged from a rare confluence of factors. Cable television flipped television imaging into overdrive, laying the groundwork for the regime of the blink, with images moving faster than conscious human perception could process them. This imaging speedup in the 1980s relied on technologies that also broadened markets, expanding fashion’s purview, as sending a message halfway around the globe in a manner of minutes and receiving shipments overnight from another continent became routine. Global mega-brands emerged, born of a scuffle in which corporate behemoths gobbled up smaller labels, consolidating the fashion landscape into a newly global business.

The “Wolf in Cashmere” and the Consolidation of Fashion

Business has always been a part of fashion, but prior to the rise of the fashion mega-brands of today, individual fashion houses had retained at least the aura of artistry. The newly international fashion world’s growing emphasis on brands blurred the line between high fashion and high finance in modeling, commercializing fashion design in unprecedented ways. Seeing the opportunity to generate customer attachment in an increasingly cutthroat field, multinational conglomerates bought up individual fashion names, plying them as brands. The Wall Street Journal fashion journalist Teri Agins reported that LVMH, the luxury-goods conglomerate, after acquiring top fashion house Dior, and later Louis Vuitton, Céline, Givenchy, Loewe, and Kenzo, began aggressively shopping for American and Italian fashion brands in the mid-nineties. Bernard Arnault, the head of LVMH, dubbed the “Wolf in Cashmere” by many, explained this strategy:

It isn’t a question of country, but a question of power of the brand and its capacity to be developed on a worldwide scale. Fashion is very different in today’s world. It is very important to link up with each other.13

After scooping up a 34 percent stake in Gucci, Arnault hired the American Michael Kors to revive the Céline brand, an increasingly typical move. Designers hopped between continents and clothing lines as their new multinational owners sought to revive dying design houses. Once parent companies called the shots, the tolerance for creative foibles diminished. In some cases, one bad collection could spell the end of a career, or designers, balking at taking orders from outsiders, quit, as was the case when designer Jil Sander “quit her eponymous house after only five months under Prada” or when “menswear designer Hedi Slimane resigned his post at Saint Laurent.”14

In the volatile climate of pitched battles for the better names, it seemed all the old rules were suspended. Arnault’s archrival, the French billionaire François Pinault, challenged LVMH’s grab at Gucci by securing a 40 percent stake in the company and combined it with Sanofi’s newly acquired existing beauty products division in a play to create a “multi-brand luxury brand group” to rival LVMH. The battle for Gucci was seen by a Wall Street Journal fashion reporter as “emblematic of the New Europe that is taking shape with the launch of the common currency and the globalization of the industry: two Frenchmen squaring off for control of a Dutch-based Italian company, run by a U.S.-educated lawyer and an American de...