![]()

1. Demography as Destiny: Falling Birthrates and the Allure of a Blended Society

Demography is the study of population, the ebbs and flows formed by the life courses of individuals.1 Today, Japan is undergoing a major demographic transformation marked by both a decline in fertility and a rapidly aging population. Fertility, the main determinant of demographic structure in any society, has declined in Japan for about four decades and in 2010 stood at 1.39, far below the replacement rate. At the same time, the elderly proportion (aged sixty-five years and above) has dramatically increased since the mid-1980s because of declined fertility and increased longevity; in 2010 it was 23.04 percent.2

Such a demographic transformation increases the gap between the productive and postproductive generation, which has a number of consequences. The social security system, for example, is strained because of the imbalance between the working-age generation who contribute to it and the retired generation who receive its benefits. In addition to this gap, the labor market has worsened since the late 2000s, particularly for young people who are delaying marriage or choosing not to marry at all. At the other end of the demographic spectrum, the elderly have drastically altered their living arrangements; the number of one-person and couple-only households has increased and that of three-generation households has declined. The welfare system, however, is premised on a familial structure (of men who work, women who take care of children and aging parents, and living arrangements based on extended or nuclear families) that is becoming outdated. Coupled with the generational gap between those contributing to, and those withdrawing from, the social security system, this means that the welfare system is getting stretched and is failing to protect more and more Japanese. One consequence is the increase in poverty, particularly among families with young children.

No European industrial country has undergone such radical shifts in demography and family structure in such a short period of time. And both the speed and depth of these changes in Japan have produced a number of social problems for which, in my estimation, no clear solutions have yet emerged. In this chapter, I discuss this demographic crisis from a sociological perspective, focusing on two specific issues: the change in family structure and the effect—of this as well as other demographic, social, and economic changes—on socioeconomic (in)equality.

Rising Inequality

Japan was the first Asian country to industrialize, and the rapid economic growth after World War II transformed its industrial structure. The primary sector shrank while the secondary and tertiary sectors expanded.3 A wave of migrants from the countryside sought jobs in the city, and the number of white-collar workers rapidly increased. An urban lifestyle emerged, and families downsized from extended (three generations) to nuclear (parents and children).

According to the Economic Survey of Japan in 1953, the nominal national income in 1951 was thirteen times larger than in 1946.4 The Income Doubling Plan launched by the Ikeda cabinet in 1960 reached its goal well ahead of the target date, earning kudos from around the world for Japan’s success. Examining how this “economic miracle” was achieved, foreign researchers began to write positively about Japan’s “lifetime employment” system.

In Japan, these economic achievements correlated with what was a widespread perception from the 1970s into the 1980s that the country had become a predominantly middle-class society—a characterization that was not entirely true, as we shall see. As the average per capita income continued to rise (despite the slight decrease in the overall economic growth after the spurt in the 1960s), people could afford automobiles and household electrical appliances (televisions, refrigerators, washing machines). Home ownership was no longer just a dream, and a middle-class consumer lifestyle became a reality for a majority of Japanese. It now became easier to buy clothes and accessories advertised in national magazines in almost every city, and this increase in consumer power across the nation blurred what had earlier been a clear urban/rural distinction. In a comparative study of income distribution in 1976, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found Japan to be the most egalitarian country of all the industrialized nations.5 Japanese took this as further evidence of exceptionalism; the self-image of a middle-class and homogeneous society encouraged the stereotype of everyone having a middle-class consciousness and sharing a common lifestyle.6

In 1984 Yasusuke Murakami declared that Japan had become a new middle-mass society where lifestyle and worldview were widely shared and class differences had faded away.7 But these confident assertions of Japan as an egalitarian society started to erode by the late 1980s as evidence of inequality started to emerge. In 1998, economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki’s best seller Economic Inequality in Japan documented that income inequality in Japan was of an order similar to that of the United States. Sociologist Toshiki Sato joined the debate with The Unequal Society, an analysis of social inequality in Japan, that found a limited degree of mobility into the upper white-collar class. Sato argued that Japan was becoming more rigidly stratified.8

Yet this contention—of Japan becoming unequal and class divided in the 1990s—assumes that Japan was once a society with a high degree of equality, and the evidence that would support this, as well as the claim of a historical devolution toward inequality in Japan, has been contested by a number of scholars.9 On the basis of his analysis of microdata concerning social status between the 1970s and 1990s, Kazuo Seiyama, for example, dismissed the assertion of Japan’s original equity as more myth than reality. According to him, there was no empirical evidence to prove that Japanese had ever achieved as widespread socioeconomic equality as it was perceived to have or that there was an explicit trend toward increasing social inequality, including a pattern of social mobility.10 Economist Tsuneo Ishikawa also cast doubt on the notion that Japanese society had ever been as egalitarian and homogeneous as was commonly supposed, on the basis of his own study of income inequality.11

The recent resurgence of interest in inequality is tied to a rising instability in the labor market that has been verified by a number of facts. For example, the number of nonregular workers has surged since the recession of the 1990s, as shown by Machiko Osawa and Jeff Kingston in chapter 3 of this volume. Youth have fallen on hard times, particularly those without college degrees. Unemployment for young people aged fifteen to twenty-four in 2011 was 11.5 percent for those with only compulsory education (middle school), while the corresponding figure for those with higher education was 8.2 percent.12 Forty-seven percent, almost half of these young people, were nonregular workers. In 2010 the proportion of nonregular workers among young workers aged fifteen to twenty-four was 45.8 percent; the corresponding figure twenty years ago was 20.2 percent, less than half.13 Not only attaining work but attaining sustainable work has become difficult for young people as the putative norm of career-long tenure with a stable employer is becoming replaced by a labor force sharply divided between those with and those without regular employment. Given how much value, and pressure, is still placed on having a stable income and job, it is not surprising that young people with blurry prospects for the future have a hard time finding a marriage partner or being willing to marry themselves. The same applies to having children.

Declining Birthrate and Recession

The main driving force behind Japan’s rapidly aging population is the continuous decline in the fertility rate, which in 2011 was 1.39, far below the replacement rate of 2.08.14 When the population as a whole started to decline in 2006, policy makers and business leaders voiced concern about economic growth and social stability in the future. Two factors largely explain the decrease in the total fertility rate: the increasing number of young people who shy away from or postpone marriage and the declining birthrate among married couples, with the latter more important in explaining the decline in the total fertility rate since the mid-1990s. The completed fertility rate for married couples was 1.96 in 2010, down from 2.23 in 2002.15 The decline was primarily a result of fewer couples having three or more children. There has not been a large increase in the proportion of married couples without children. Only 6.4 percent of couples who have been married for fifteen to nineteen years are childless, a 3 percent increase from 2002, but still insignificant.16

The fertility rate has been below the replacement rate for more than thirty years. The so called “1.57 shock” in 1990 was the tipping point when the government took official notice of the problem and began to introduce social policies to support families with young children. The measures included maternity leave and a family-care leave system for caregivers of children or frail family members (1991),17 as well as the Angel Plan (1994) to make companies and the government (central and local) more involved in child care.18

Subsequently, other measures were taken to address the decline in birthrate and marriage rate and to reconcile child rearing with work. The thinking in these plans also became more complicated and expansive. The new Angel Plan (1999), for example, factored in not only child care outside the home but also the employment system and education as complicit in fertility rates.19 To date, however, these policies have not yet boosted the total fertility rate. One reason for this is undoubtedly the continuation of instability in the labor system.

Until the mid-1990s, the decline in fertility was explained mostly in terms of the increasing number of unmarried people. Because only 2 percent of children are born out of wedlock in Japan, marriage and childbirth are closely related.20

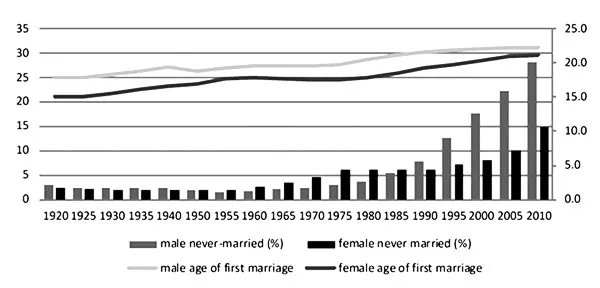

Figure 1.1 shows trends in the average age of first marriage for men and women and changes in the proportion of people who never marry. For both men and women, there is an increased tendency to marry later (if at all). From 1960 to 2010, the average age at first marriage rose by roughly five years for men and six years for women. More recently we have also seen a narrowing of the age gap between husband and wife, roughly halving from a peak of about 3.7 years in 1985 to 1.5 years in 2010. The proportion of people spending their whole life unmarried rose sharply in the 1990s. Until the 1980s more women than men never married, but that pattern was reversed in the late 1980s, and the never-married rate has continued to climb steeply for men ever since. The never-married rate of men was 20.1 percent and that of women was 10.6 percent in 2010.21 Among ...