![]()

1

Bahá’í History, Beliefs, Outreach, and Administration

Like all world religious movements, the religious history of the Bahá’í Faith is complex. While many book-length volumes have been written about Bahá’í history (e.g., Smith 1987, 1996; Momen 1996; Stockman 1985, 1995; Garlington 2005; and even Shoghi Effendi (Rabbani 2010) wrote a history of the Bahá’í Faith commemorating its centenary), this chapter will present a brief overview of this little-known and rarely analyzed world religion to help us understand its sociological uniqueness.

Bahá’í History in Iran and the Middle East

Shi‘ite Expectations and the Bábí Religion

Bahá’í history begins with messianic movements in the Islamic as well as Christian world.1 The Bahá’í Faith grew out of Shi‘ite Islam, specifically Twelver Shi‘ism, the largest of Shi’ite sectarian groups (Momen 1985). Shi‘ites believe that the correct line of successors to the Prophet Muḥammad began with his cousin and son-in-law, ‘Alí ibn Abí Tálib (who is recognized as the fourth Imam or successor by the Sunni community). ‘Alí begins a line of twelve Imams who lead the Shi‘ite faithful, until the disappearance in 874 A.D. of the Twelfth Imam, Muḥammad al-Maḥdi, who it is believed will return from hiding (or “occultation”) at the end of the age. Thus, since the late ninth century, Shi‘ite Islam has developed a strong messianic motif (see Smith 1987) waiting for the return of the Twelfth Imam to lead the Muslim faithful (see also Armstrong 2000).

This history becomes further complicated by the Twelver Shi‘ite doctrine of the báb (which means “door” or “gate” in Arabic). After the disappearance of the Twelfth Imam, the Shi‘ite community was led by a series of four bábs who were gates to the Hidden Imam, who also predicted the return of the Maḥdi or Twelfth Imam (also called the Qá’im in Shi‘ism). Both Sunni and Shi‘ite theology state that the Maḥdi would rule the world for seven, nine, or nineteen years before Jesus returned (Momen 1985).

In 1844, as Shi‘ite expectations were at their peak, a Persian merchant named Sayyid ‘Alí-Muḥammad revealed himself to be the Qá’im (“He Who Ariseth”) and took the title of the Báb (eventually, Bahá’ís came to recognize the Báb as an independent “Manifestation of God” with the same rank as Moses, Jesus, or Muḥammad). The assertions of the Báb were a challenge to the ‘ulama and Shi‘ite political authority of Iran. Bolstering the Báb’s popular claims was the fact that in 1844 (1260 A.H. in the Islamic calendar), when he made his declaration, a full thousand years had passed, as prophesied since the original disappearance of the Twelfth Imam in 260 A.H. (Smith 1996). From a Bahá’í point of view, the crux of the Báb’s message was the heralding of the coming of the “One Whom God Will Make Manifest,” a prophet of greater importance who would lead humankind into a new era of peace. After amassing a following (known as Bábís), the Báb was arrested and put in prison. On July 9, 1850, the Báb, along with one of his followers, was executed by gunfire in Tabriz (Smith 1996). With many of the most devout Bábís killed, and now their leader assassinated, the Bábí movement was in tatters, and what was left of it was driven underground. Only the most faithful Bábís continued to believe that the Báb indeed had been the promised return of the Twelfth Imam, and clung to his prophetic vision.

The Rise of the Bahá’í Faith

The second great figure of early Bahá’í history was Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí, a Persian whose family was part of the governing class of the country. Upon hearing of the religion of the Báb, he converted and began teaching its message. His growing leadership role within the Bábí movement revitalized and invigorated the new religion in the wake of the Báb’s execution. Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí’s social position protected him at first from the persecutions of the Persian authorities, but as fervor increased, he too was imprisoned (Hatcher and Martin 1985). While in prison in Tehran in 1852–53, Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí himself said that God had revealed that he was the “One Whom God Will Make Manifest” prophesied by the Báb, whose teachings would usher in the Kingdom of God. Rather than execute a member of Persia’s upper class, Persian authorities exiled Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí, his family, and fellow Bábís to Baghdad, thus beginning a lifetime of imprisonment. While in Baghdad, Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí took the title Bahá’u’lláh (“The Glory of God” in Arabic), and announced that he was the one promised by the Báb, whereupon the vast majority of Bábís pledged allegiance to Bahá’u’lláh (formerly Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí) and accepted his authority as a new religious prophet (for a more detailed history, see Rabbani 2010). The lifelong imprisonment of Bahá’u’lláh, and even the modern-day persecution of Bahá’ís in Islamic countries, follows from Bahá’í claims that the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh are divine prophets who were sent by God after Muḥammad revealed Islam. Thus, Bahá’ís are considered heretics by Islamic clerics because they have reinterpreted the dogma that Muḥammad is the “seal of the prophets” to mean the last prophet of a participuar cycle of God’s revelation, not the final prophet ever to be sent by God.

In 1863, the group of Bahá’ís (the new name given to the followers of Bahá’u’lláh) were banished from Baghdad and sent to Constantinople (now Istanbul) and then to Adrianople (now Edirne) in Turkey. Finally, in 1868 the group was exiled permanently to ‘Akká, Palestine, the prison-city of the Ottoman Empire (‘Akká is near present-day Haifa, Israel, the location of the current Bahá’í World Centre). Here, as in the other cities of his banishment, Bahá’u’lláh carried on his ministry, writing nearly one hundred volumes that partially comprise Bahá’í scripture, and met with pilgrims who traveled to ‘Akká to see the man whose message was spreading throughout Persia and the Middle East.

When Bahá’u’lláh died in 1892, he left behind a growing movement, and a will and testament that named his eldest son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (“Servant of Glory” in Arabic, also known by Bahá’ís as “the Master”) his successor and the authoritative interpreter of Bahá’í writings (although Bahá’ís do not consider ‘Abdu’l-Bahá a Manifestation of God, as is Bahá’u’lláh). After the Young Turk revolution in 1908, all political and religious prisoners of the Ottoman Empire were released, thus freeing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to travel and to begin establishing his father’s Covenant: the institutionalization of the Bahá’í Administrative Order as communicated through Bahá’u’lláh’s writings (Hatcher and Martin 1985).

In implementing Bahá’í teachings, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá helped to define two major institutions: the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice. The Guardianship imparted sole authority of the religion to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi, who would continue to erect the religion’s Administrative Order. Upon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s death in 1921, Shoghi Effendi led the Bahá’í Faith as its “Guardian” until his death in 1957. From 1957 until the first election of the Universal House of Justice in 1963 by the members of all the National Spiritual Assemblies, the “Hands of the Cause of God,” a temporary administrative institution of charismatic, faithful Bahá’ís (first inaugurated by Bahá’u’lláh), governed the Bahá’í Faith. Since 1963, the Universal House of Justice has led the world’s approximately six million Bahá’ís.

Toward the end of his life, Bahá’u’lláh appointed four persons as “Hands of the Cause of God” to promote the interests of the Bahá’í Faith, and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá conferred this rank on a few individuals posthumously. However, it was Shoghi Effendi who most utilized these individuals in the erection of Bahá’í institutions. In ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Will and Testament (1990), Shoghi Effendi was given the authority to appoint Hands of the Cause in his role as Guardian, as well as the authority to appoint the succeeding Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith. The successor to the Guardian was either to be the “first-born” of his lineal descendants or, if the first-born lacked the necessary spiritual qualifications, then Shoghi Effendi was to appoint one of the male descendants of Bahá’u’lláh as the Guardian (Taherzadeh 1992).

During his tenure as Guardian, Shoghi Effendi appointed thirty-two Hands of the Cause of God (Taherzadeh 1992) to be his personal deputies in the protection and propagation of the Bahá’í Faith. However, Shoghi Effendi and his wife never had any children, and all of Bahá’u’lláh’s descendants at the time of Shoghi Effendi’s death had been excommunicated because of their opposition to the Bahá’í Faith and their “violation of the Covenant.” Since there was no provision in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Will and Testament for these circumstances, there have been no additional Guardians in the Bahá’í Faith since Shoghi Effendi’s death in 1957. However, Bahá’ís say that the “institution of Guardianship” continues through the guidance given to the Bahá’í world through Shoghi Effendi’s voluminous writings and personal correspondence. Since ‘Abdu’l-Bahá conferred authority only on the Guardian to appoint Hands of the Cause, and since all remaining Hands of the Cause have passed away, this institution of the Administrative Order remains vacant (and the authority to excommunicate therefore falls solely to the Universal House of Justice).

Bahá’í Administrative Order

Bahá’ís consider their Administrative Order to be unique among the world’s religions because Bahá’u’lláh provided the blueprints for the Administrative Order in his Writings. A Bahá’í author said about the Bahá’ís’ unique organizational system: “Not until the advent of the Bahá’í Dispensation did a Manifestation of God include administrative principles among His spiritual teachings. This is an entirely new dimension which Bahá’u’lláh has introduced; He has placed the spiritual and administrative principles on a par with each other. A violation of an administrative principle . . . is as grave a betrayal of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh as breaking a spiritual law” (Taherzadeh 1992, p. 395).

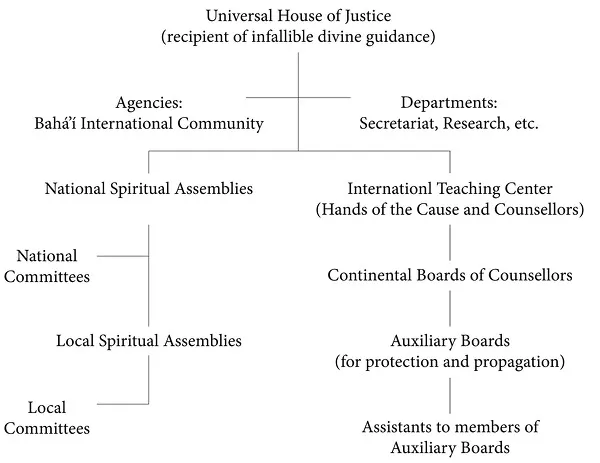

The Bahá’í Administrative Order (as outlined in Bahá’í Writings or holy scripture) consists of two pillars, or functional branches. These two branches evolved, to use sociologist Max Weber’s (1946) terminology, to routinize the charismatic authority of the Central Figures (the Báb, Bahá’u’lláh, and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá) of the early history of the Bahá’í Faith. This is significant for Bahá’ís, because Bahá’u’lláh strictly forbade the formation of clergy in the Bahá’í Faith (Bahá’u’lláh 1992; Esslemont 1970). As we will see, as part of the Bahá’í ideology of “progressive revelation,” Bahá’ís believe that humanity has developed beyond the need for a special class which monopolizes religious knowledge. Bahá’ís claim that the lack of clergy protects their faith from being corrupted by the power which accrues to any individual. In the Bahá’í Faith, no one Bahá’í has any formal authority over anyone else. Instead, all religious authority lies in councils or assemblies which operate at all levels of society. These two branches (or pillars) of the Administrative Order consist of: 1) elected assemblies (the “Rulers”) and 2) appointed boards (the “Learned”) operating at the local, national, and international levels of society—see Figure 1.1.

The Rulers. The first of the two branches of Bahá’í administration is a series of democratically elected “spiritual assemblies” at the local, national, and international levels of social life (referred to as the “institution of the Rulers” since they are that branch of the Administrative Order that governs or has authority over the Bahá’í community). Each year, wherever there are at least nine adult Bahá’ís—age twenty-one and older—within a recognized municipal boundary, an election is held to form a Local Spiritual Assembly (LSA), which constitutes the bedrock authority of local Bahá’í community life. Every adult community member is on the ballot and entitled to vote for nine individuals, and the nine receiving the most votes become LSA members—this is true of Bahá’í elections at all three levels of the structure.2 Local elections take place on the first day of the twelve-day Festival of Riḍván held April 21–May 2 each year. The Riḍván festival (meaning “paradise” in Arabic) commemorates the public declaration in 1863 of Bahá’u’lláh as a Manifestation of God in a garden outside Baghdad, Iraq, during his exile. There are approximately 1,100 LSA jurisdictions in the United States. None of the individuals who are elected to the assemblies have any authority—only the decisions arrived at through consultation by the institution are authoritative. If there is a tie for the ninth spot, Bahá’í administrative law dictates that the position go to the individual who is a “minority” in the community (a form of electoral “affirmative action” to promote unity in diversity—the most important Bahá’í social principle). Bahá’ís are not allowed to “run” for office, since Bahá’u’lláh strictly forbade campaigning in his Writings. Instead, Bahá’ís are instructed to vote for any Bahá’í who is eligible based on his or her spiritual character. Shoghi Effendi (Rabbani 1974) instructs Bahá’ís in all elections to vote only for those “who can best combine the necessary qualities of unquestioned loyalty, of selfless devotion, of a well-trained mind, of recognized ability and mature experience” (p. 88).

Usually during the first weekend in October, Bahá’ís in the United States attend their Unit Convention, an administrative meeting where a National Delegate is elected—the first step in the formation of the National Spiritual Assembly (NSA), the next level up in this branch of the Administrative Order. Units are composed of groupings of several LSA jurisdictions and Bahá’í Groups (a “group” numbers between two and eight Bahá’ís in a municipality) of roughly equal Bahá’í population. There are 158 districts or units in the United States. These two elections—the April Riḍván festival, and the October Unit Convention—are the two democratic ceremonies in which all Bahá’ís have a chance to participate; indeed, voting in them is viewed as a spiritual obligation for members, and part of the way all Bahá’ís can participate actively in the building of a global civilization.

The elected National Delegates then go to the National Convention (held in Wilmette, Illinois—site of the American Bahá’í National Center) in May to elect the National Spiritual Assembly—again, a nine-member body that oversees Bahá’í activity within a nation or region. Often, the National Delegates will return to their Unit jurisdiction and hold a meeting to report on the consultation from the National Convention (the proceedings are also summarized in the periodical publication of the NSA, The American Bahá’í, sent to every Bahá’í household in the United States). Unlike officials or representatives in many electoral systems, Bahá’í delegates or assembly members are not bound to “represent” the choices of their “constituents”—rather, they are elected based on their spiritual character to vote their own conscience for the good of the Bahá’í community in their jurisdiction.

The National Spiritual Assembly of the United States has various departments and agencies. These include the National Archives, the Office of Education and Schools (there are three permanently staffed Bahá’í schools that sponsor conferences and retreats for both Bahá’ís and non-Bahá’ís: Bosch Bahá’í School in Santa Cruz, California; Louhelen Bahá’í School in Davison, Michigan; and Green Acre Bahá’í School in Eliot, Maine), the Persian-American Affairs Office (to ease the transition of transplanted Iranians to American culture), the U.S. Bahá’í Media Services Office, the Office of Assembly Development, the Bahá’í Publishing Trust, the Office of International Pioneering, and the Office of Public Affairs. The latter has lobbied the U.S. Congress to pass resolutions condemning the persecution of Bahá’ís in Iran.

Finally, once every five years, beginning in 1963, the members of all the NSAs in the world gather at the Bahá’í World Centre in Haifa, Israel, to elect the nine-member Universal House of Justice, the highest authority in the Bahá’í world. Unlike the LSAs and NSAs, Bahá’u’lláh’s Writings exempt women from serving on the Universal House of Justice. Bahá’u’lláh promised Bahá’ís that decisions made by the Universal House of Justice are divinely guided and infallible. Although the Universal House of Justice cannot change any law revealed in Bahá’u’lláh’s scriptures, it is empowered to legislate on all matters “which have not outwardly been revealed in the Book” (Bahá’u’lláh 1992, p. 3), and it can also modify its own laws as historical circumstances demand. It can thus repeal or change its own legislation (but not laws revealed by Bahá’u’lláh). This administrative flexibility prevents the religious laws and organization of the Bahá’í Faith from becoming obsolete, which often resulted in sectarian divisions throughout history. Consequently, Bahá’ís believe that through the collective decisions of the institution of the Universal House of Justice (again, not based on any individual charismatic authority), the Bahá’í world, and eventually the global civilization which will be generated from Bahá’í institutions and laws, is as...