The Psychology of Tort Law

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Psychology of Tort Law

About this book

Tort law regulates most human activities: from driving a car to using consumer products to providing or receiving medical care. Injuries caused by dog bites, slips and falls, fender benders, bridge collapses, adverse reactions to a medication, bar fights, oil spills, and more all implicate the law of torts. The rules and procedures by which tort cases are resolved engage deeply-held intuitions about justice, causation, intentionality, and the obligations that we owe to one another. Tort rules and procedures also generate significant controversy—most visibly in political debates over tort reform.

The Psychology of Tort Law explores tort law through the lens of psychological science. Drawing on a wealth of psychological research and their own experiences teaching and researching tort law, Jennifer K. Robbennolt and Valerie P. Hans examine the psychological assumptions that underlie doctrinal rules. They explore how tort law influences the behavior and decision-making of potential plaintiffs and defendants, examining how doctors and patients, drivers, manufacturers and purchasers of products, property owners, and others make decisions against the backdrop of tort law. They show how the judges and jurors who decide tort claims are influenced by psychological phenomena in deciding cases. And they reveal how plaintiffs, defendants, and their attorneys resolve tort disputes in the shadow of tort law.

Robbennolt and Hans here shed fascinating light on the tort system, and on the psychological dynamics which undergird its functioning.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

The Real World of Torts

The Pattern of Tort Disputes

The Real Worlds of Torts

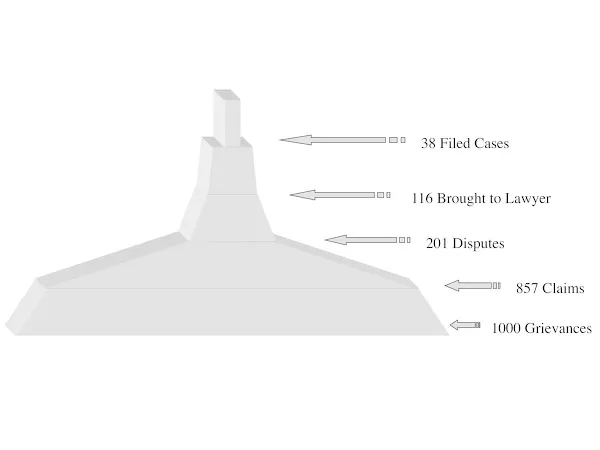

The Disputing Pyramid

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Real World of Torts

- 2. Intentional Torts

- 3. Negligence

- 4. Causation

- 5. Limits on Liability: Duty and Scope of Liability

- 6. Damages

- 7. Defenses

- 8. Products Liability

- Conclusion: A Psychological Perspective on Tort Rules, Tort Cases, and Tort Reform

- Appendix: Psychology and Torts

- Notes

- Subject Index

- Name Index

- About the Authors