![]()

1

Neighborhood Councils

City Hall Competes with the Street for Legitimacy

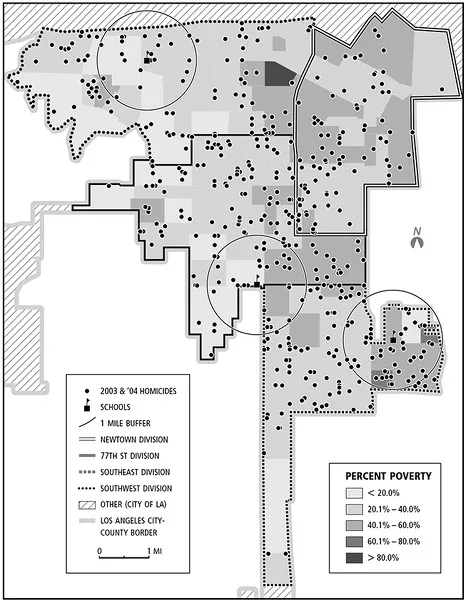

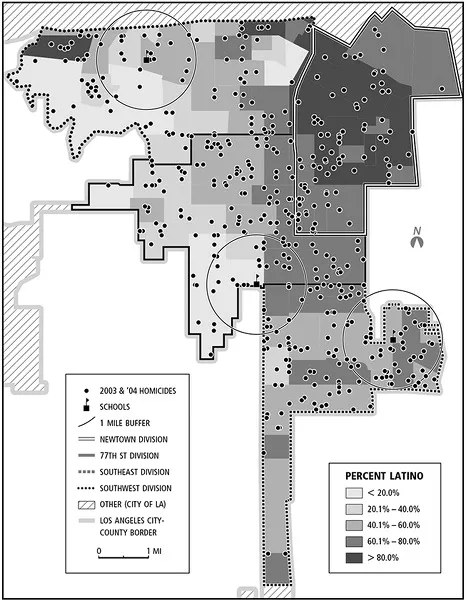

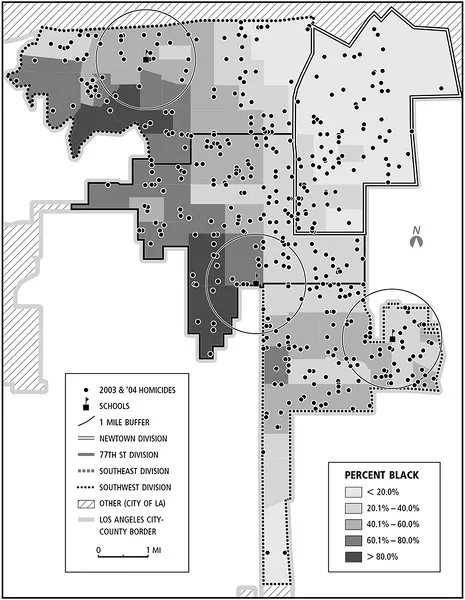

Los Angeles recorded 508 murders in 2003 and 516 in 2004—a total of 1,024 murders. According to data collected by the Los Angeles Police Department, each year nearly half of these murders were committed in South Los Angeles (see Table 1.1).

Many of the residents exposed to violence are African Americans and Latinos who live in high-poverty neighborhoods. (Maps 1.1–1.3 reflect the poverty rates and racial makeup of the neighborhoods.)

| TABLE 1.1. Homicides by Police Division in South Central Los Angeles |

| | Area (square mi) | 2003 Homicides | % of 2003 Homicides | 2004 Homicides | % of 2004 Homicides | 2003 & 2004 Total Homicides |

| Los Angeles | 503 | 508 | | 516 | | 1024 |

| South Central | 42.7 | 238 | 46.85 | 265 | 51.36 | 503 |

| Newton | 9.8 | 46 | 9.06 | 45 | 8.72 | 91 |

| 77th Street | 11.3 | 64 | 12.60 | 88 | 17.05 | 152 |

| Southeast | 9.3 | 77 | 15.16 | 71 | 13.76 | 148 |

| Southwest | 12.3 | 51 | 10.04 | 61 | 11.82 | 112 |

| Source: LAPD |

How do poor residents of South Los Angeles respond to such high levels of violent crime? This chapter answers this question by examining how local political institutions respond to violence. I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in eight separate City of Los Angeles Neighborhood Councils located in South Los Angeles. The Neighborhood Councils were located within the boundaries of four Los Angeles police divisions—Southeast, Southwest, Newton, and 77th Street (known as “the 77th”).

A brief history of Los Angeles municipal government is needed to place the literature within context. Unlike other major cities in America, the unique form of municipal government in Los Angeles emerged as a result of the reform movement in the 1920s. Fearful that Los Angeles would end up like the “machine-style” political systems of local government in New York and Chicago—which were viewed as corrupt and dominated by ethnic European immigrants—members of the reform movement sought to put an end to this style of local politics.

Beginning in the 1920s, Los Angeles established a style of local government that was designed to maximize participation of the white, middle-class Protestants who migrated to Los Angeles from the midwestern and eastern United States. At the same time, this form of government was meant to minimize the participation and influence of European immigrants, Mexican Americans, African Americans, and other marginal groups who threatened the reform vision of morality. The reform type of local governance became the institutional basis for the City of Los Angeles until the mid-1990s, when the city charter was reformed. Thus, local government in the southwestern United States was run like a business, free of partisan favors, and was never designed for broad inclusion of residents of diverse backgrounds.

What are the consequences of reform types of governance on the modern metropolis of Los Angeles, and how does the governing structure of Los Angeles help us to understand how political institutions respond to violence? To answer this question, it is important to note the impact reform types of government have had on the poor since their inception in Los Angeles. Bridges (1997) argues that the urban poor were better served in the machine forms of government as opposed to the reform types of governing structures. Because machine forms of governance were better connected to residents, they were able to provide direct benefits and were better able to teach them how the political process operates, and, thus, have their voices heard. Therefore, one major and significant effect of reform government was that the ties that connected the local government and the poor communities of Los Angeles became weak and poorly developed.

The organizational structure of reform governance is significant because it shaped the relationship, over time, between Los Angeles municipal government and poor communities such as South LA. Examining the historical relationship between local government and poor communities is a crucial analytical move required to understand how local political governance affects poor communities (Abu-Lughod, 2007). The historical relationship, rather than a period in time, is the key to understanding how local government is likely to respond to crime and rioting. Sociologist Abu-Lughod developed an analytical concept for examining the historical relationship between local government and urban poor communities, which she termed “political culture.”

Abu-Lughod argues that much of the urban unrest in cities such as Los Angeles can be attributed to race relations, segregation, and the role of local government and its relationship to poor communalities of color. The key factor, however, is political culture, since it emphasizes the role of local government. Abu-Lughod finds that many of the major uprisings and riots in Los Angeles were affected by the historical legacy of poor ties between City Hall and the poor residents of LA, who reside mainly in South LA and East LA. Beginning with the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943, many Mexican Americans had little political representation to voice their concerns through formal political channels and to address grievances such as housing, job discrimination, and abuse by the police. These frustrations were made manifest in riots between US servicemen and Mexican Americans, including African Americans and Filipinos.

The political culture of Los Angeles also shaped the context for two of the largest riots in America’s history. Beginning in World War II, many African Americans were recruited from the South to Los Angeles for industrial work. They were economically integrated through employment, but not politically integrated. Many of these African Americans, through a variety of means, were segregated into the southern part of Los Angeles to form the largest ghetto west of the Mississippi, in what became known as South Central Los Angeles. Poor relationships between the Los Angeles Police Department and residents of South LA became the norm. The inability of City Hall to address these grievances set the stage for the 1965 Watts Riots.

The 1992 riots were precipitated by many of the same factors as the riots of 1965 (Abu-Lughod, 2007). Although a black mayor, Tom Bradley, had been first elected in 1973 and was still in office, many of the problems of the 1960s had never been addressed—for example, abuses by the police and housing discrimination. Instead, many of the problems were amplified: unemployment, which was spurred by white flight after the 1965 riots, and deindustrialization, as a result of the global economy. The inability of City Hall to address these issues set the stage for the largest riot in the United States since the 1960s.

The disconnect between city government and residents of Los Angeles came to a head following the 1992 riots, when many Angelenos began to consider splitting the city into two parts, in what became known as the secession movement. Like the previous periods of unrest outlined thus far, the major motivating factor for splitting the city was that it was out of touch with the needs of residents. Residents from the Valley and Westside complained that City Hall did not address the unique needs of their segments of the city. So, the idea that City Hall was out of touch and disconnected was not exclusive to the poor, but was viewed by Angelenos from different parts of the city and from different backgrounds as a major problem.

Fortunately, the city was spared from division by a charter reform measure that would help to make government more responsive to the needs of Angelenos. There were several key features in the newly formed city charter, but the one element that would bring government down to the communities was the creation of what would be known as the Neighborhood Councils. Essentially, the new charter created a three-tiered government: mayor, City Council, and Neighborhood Councils. The Neighborhood Councils were, in theory, supposed to represent the needs of a small number of neighborhoods and a considerably smaller number of residents. Thus, the new charter created a mandate for a new type of local governance that was decentralized institutionally.

My analysis picks up where Neighborhood Councils entered the picture. The questions that many scholars now must consider are: How much more effective is a decentralized form of government in addressing issues such as violence? Is it able to overcome the weak ties and disconnect that characterized the previous relationships in the reform style of government?

A burgeoning literature is emerging that attempts to examine the effectiveness of decentralized government in addressing issues such as crime and violence. Berry, Portney, and Thomson (1993) argue that decentralized forms of government, which include the Neighborhood Councils, can effectively enhance democracy at the neighborhood level to address the issues of crime and violence. Archon Fung (2004) advances this body of work by highlighting the importance of “deliberative practices” in decentralized government settings. For Fung, decentralized governments are not sufficient to make local government responsive to community needs. Instead, institutionalized, deliberative practices are needed to overcome the challenges that decentralized governments face, for example, heterogeneity, poverty, and interracial differences.

Important conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of LA’s municipal government if one considers the implications of the research conducted by Berry et al. and Fung. Although the governing structure of Los Angeles has transitioned into a more decentralized form of governance, the preconditions necessary for a more effective government, which would make City Hall more responsive, are lacking in two serious ways. First, LA’s Neighborhood Councils have only advisory power in zoning decisions that may affect residents. According to Barry et al. however, for decentralized forms of government to be effective they must have autonomous power to make decisions regarding issues that impact the community. A second issue that undermines the ability of LA’s newly formed decentralized government, according to Fung’s framework, is the absence of “deliberative practices” that keep decentralized domains of government, such as Neighborhood Councils, from slipping into conflict, disorderliness, and dominance by local elites. Fung argues that without institutionalized, deliberative practices, decentralized governments run the risk of slipping into what he calls a free-for-all form of laissez-faire. Finally, Fung argues that for municipal government to be effective it must be bottom up, where citizens play an active role directing services. However, in LA’s newly revised, decentralized municipal government, many policy decisions continue to be top down.

Building on these insights, I argue that although the newly formed, decentralized municipal government of Los Angeles is making progress toward connecting citizens, the legacy of the Reform Era continues to shape the relationships between poor communities, in particular South Los Angeles and City Hall. I illustrate how many of the same problems that emerged from those weak relationships, for example, the criminalization of African Americans and Latinos and the inability to provide adequate services to address issues such as violence, continue to plague residents in South LA.

What the research on urban politics has demonstrated is that reform government tends to have weaker ties to residents, making it difficult for local government to respond to local issues such as crime. The contemporary literature on urban politics, however, is more optimistic about the possibility of overcoming the weaknesses in traditional forms of government through decentralized municipal governance.

However, this work adds another dimension to the literature that has not yet been addressed. I demonstrate the new challenges that LA’s decentralized forms of governance face by examining the Neighborhood Councils. I suggest that LA city government must now compete with alternative forms of governance that have arisen because of the vacuum created by a lack of services. More specifically, the Los Angeles case shows how the authority of local government is challenged by alternative forms of governance, which emerged in the absence of good relationships between City Hall and South Los Angeles. I focus on two elements of this alternative governance. First, I show how City Hall must compete with the street for legitimacy. Second, I demonstrate that an important dimension of alternative governance in South LA is the emergence of a divided community, where interracial relations act as a division between what are actually two communities that coexist in the same social space. The result of this competing form of governance weakens the ability of government to effectively address issues of violence at the local level.

The ghost of Reform Era practices and the emergence of alternative governance, rooted in the criminal underground, present new challenges that undermine the legitimacy of City Hall and thus its effectiveness in addressing violence in South LA.

The Ghost of the Reform Era: The Criminalization of and Governmental Disconnect from the Urban Poor

In this section, I outline two main strategies used by participants in the Neighborhood Councils to manage violence: (1) directing services and (2) holding local law enforcement accountable for their policies. Focusing on the strategies utilized by community residents is significant for two reasons. First, these strategies illustrate the agency of actors and the role that the Neighborhood Councils have in responding to violence. Second, and, more importantly, they show the structural limitations of municipal government in addressing violence through formal, political, institutional means.

This chapter illustrates how these strategies were undermined by poor relations and weak social ties between City Hall and residents of South LA. Furthermore, it illustrates how residents continue to feel criminalized through the suppression tactics of law enforcement. However, the newly formed Neighborhood Councils add a layer of government to connect citizens in a manner that did not exist in the past. I suggest that although City Hall is making progress in connecting residents, serious obstacles rooted as far back as the Reform Era persist.

Directing City Services to Combat Violence

A primary strategy utilized by members of the Neighborhood Councils was to direct city services to areas that residents perceived to have high crime and violence. Neighborhood Councils brought together community residents from various backgrounds; however, the Neighborhood Councils mostly consisted of African American homeowners, nonprofits, church leaders, and a handful of Latino business owners. Homeowners who were not affiliated with churches, non...