eBook - ePub

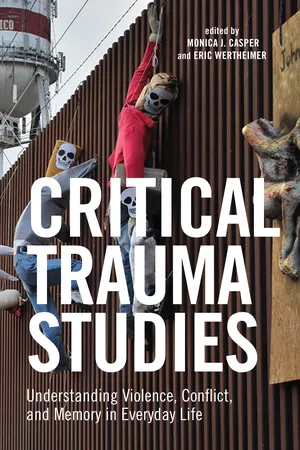

Critical Trauma Studies

Understanding Violence, Conflict and Memory in Everyday Life

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Critical Trauma Studies

Understanding Violence, Conflict and Memory in Everyday Life

About this book

Trauma is a universal human experience. While each person responds differently to trauma, its presence in our lives nonetheless marks a continual thread through human history and prehistory. In Critical Trauma Studies, a diverse group of writers, activists, and scholars of sociology, anthropology, literature, and cultural studies reflects on the study of trauma and how multidisciplinary approaches lend richness and a sense of deeper understanding to this burgeoning field of inquiry. The original essays within this collection cover topics such as female suicide bombers from the Chechen Republic, singing prisoners in Iranian prison camps, sexual assault and survivor advocacy, and families facing the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. As it proceeds, Critical Trauma Studies never loses sight of the way those who study trauma as an academic field, and those who experience, narrate, and remediate trauma as a personal and embodied event, inform one another. Theoretically adventurous and deeply particular, this book aims to advance trauma studies as a discipline that transcends intellectual boundaries, to be mapped but also to be unmoored from conceptual and practical imperatives. Remaining embedded in lived experiences and material realities, Critical Trauma Studies frames the field as both richly unbounded and yet clearly defined, historical, and evidence-based.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Critical Trauma Studies by Monica Casper,Eric Wertheimer,Eric Wertheimer, Monica J. Casper, Eric Wertheimer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Genderforschung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Within Trauma

An Introduction

Eric Wertheimer and Monica J. Casper

As the problematic became absorbed into the taken-for-granted, the vulnerable self merged into biography. Body and self were mutually implicated in that biography of vulnerability.

—Virginia Olesen (1992, 210)

There is no life without trauma. There is no history without trauma . . . Trauma as a mode of being violently halts the flow of time, fractures the self, and punctures memory and language.

—Gabriele M. Schwab (2010, 42)

Ground Truths

The Sonoran Desert in autumn, after the heat, is beautiful. Hackberries and wolfberries emerge and barrel cacti blossom. Wildflowers open out in magenta, saffron, Indian red, and burnt orange, feeding butterflies and bees. Snakes map their route to winter sleep, lizards grow sluggish, and winged raptors—wintering hawks, kestrels, falcons, and owls—soar above the cover of fallen petals from summer-blooming perennials. And yet, the pastoral desert is also predatory. Lacerated mesquite trees bleed black sap. Cacti of all shapes and sizes protect themselves with spikes and spurs. Deadly heat, especially in high summer, leeches moisture from flesh, leaf, bone, and tongue. Bullets target humans and animals, leaving corpses and despair in their path. Migratory trails, littered with debris and remains, are haunted by the ghosts of the men, women, and children who walked them, entire families seeking a better life among people who hate and fear.

It is here, in this contradictory desert landscape in which we live and labor, that we began to assemble a working hypothesis about what it means to do intellectual work in the midst of great trouble. We take seriously Bruno Latour’s (2004, 239) question, with particular attention to the challenge of his metaphorical pessimism: “Is it so surprising, after all, that with such positions given to the object, the humanities have lost the hearts of their fellow citizens, that they had to retreat year after year, entrenching themselves always further in the narrow barracks left to them by more and more stingy deans? The Zeus of Critique rules absolutely, to be sure, but over a desert.”

In the spirit of Latour’s inquiry—but refusing the stereotype of the geographically and epistemologically negative space of the desert—we seek to foster a new humanities, one that respects fact and heart even after the disciplines have diverged over arguments about society and imagination, propaganda and information, constructs and cold reality, representation and experience. Our work is thus keen to meld the scientific with the affective, the voices of narrated pain with the determined habits of repair and psychic healing, the archives and realms of theory with the visceral, lived experiences of practice. Our approach is hybrid and interdisciplinary, accustomed as we are to inhabiting geographic and intellectual spaces shaped by plurality, risk, and diverse modes of being.

A Genealogy of Critical Trauma Studies

Critical Trauma Studies: Understanding Violence, Conflict, and Memory in Everyday Life is located both within and after various iterations of the entity known as “trauma studies.” In the field’s initial configuration, scholars challenged and deliberately moved away from psychiatric and/or biomedical approaches to trauma, which had dominated the field (e.g., Ball 2000; Fassin and Rechtman 2009). In mid- to late nineteenth-century framings, “trauma” was a disease of the mind, conceptualized as “traumatic neurosis” generated by railroad accidents (Erichsen 1867) and later as war-related “shell shock” and posttraumatic stress disorder, or PTSD (Young 1997). The condition of trauma became a target for biomedical and psychiatric intervention, and in Foucauldian terms, traumatized individuals became subjects of and to various disciplinary practices that congealed around them. To be traumatized meant that one was psychically wounded and vulnerable, unwhole; therapeutic practices were aimed at “restoring” normalcy or stasis.

Epistemological shifts in which historians, cultural theorists, and others unraveled these biomedical and psychiatric meanings of trauma have led to a rich and robust body of work exploring, for example, history and memory (e.g., Caruth 1995; LaCapra 2001), narrative and its limits (e.g., Scarry 1985; Caruth 1996), memorialization (e.g., Sturken 1997, 2007; LaCapra 1998), cultural representations of trauma (e.g., Kaplan 2005), and genealogies of trauma (e.g., Leys 2000; Orr 2006). Taken together, these contributions have brought the study of trauma firmly within the purview of the humanities and social sciences, recognizing and naming “trauma” not only as a condition of broken bodies and shattered minds, but also and primarily as a cultural object. In these framings, “trauma” is a product of history and politics, subject to reinterpretation, contestation, and intervention.

Of course, these epistemological reframings do not diminish the reality of events. Earthquakes strike, buildings fall, and people die; bodies are devastated by bullets and bombs; famine, drought, and genocide decimate entire populations; planes crash (and disappear), trains derail, and cars smash into each other, twisting metal and limbs; loved ones become sick and die, or they are brutally murdered; sexual assault is pandemic; tornados and hurricanes rip houses off their foundations and children from their parents’ arms; wars shred lives, communities, and landscapes and send soldiers home in body bags. These events are recursive. Categorizing and responding to them not merely as events, but as traumatic events, with its helpful vocabularies, knowledges, and temporalities, is the stuff of critical trauma studies. The field seeks to reveal the processes by which things that happen are denoted as trauma. Critical trauma studies asks: What does it mean to use the discourse of trauma? To represent events as ruptures, breaks, and other deviations from the normal? And what, then, is the normal?

We are speaking here of “trauma studies” as if it is an established area of study. And indeed, there is a significant and influential body of work. But there is relatively little structural coherence to the field, especially compared to other interdisciplinary areas like disability studies, American studies, and gender studies, all of which have become institutionalized to a much greater degree. This is both the virtue and ongoing (albeit productive) problem of critical trauma studies. The boundaries, scope, and content of the field are fluid and contested (Stevens 2011), as they have been from its inception. Yet the field, such as it is, has been forged through shared intellectual considerations of “modern” catastrophes such as war, genocide, forced migration, and 9/11, alongside everyday experiences of violence, loss, and injury. If there can be a conceptual heart of critical trauma studies—a domain of inquiry as various and global as its subject—we’d settle on a set of centripetal tensions: between the everyday and the extreme, between individual identity and collective experience, between history and the present, between experience and representation, between facts and memory, and between the “clinical” and the “cultural.”

A genealogy of trauma, such as historian Ruth Leys (2000) has provided, must inevitably travel through the historical development and deployment of PTSD, as well as other analytic objects of trauma, such as memory, narrative, representation, and materiality. However, such a genealogy might also travel through social theory, through the epistemes that gave birth to a proliferation of ideas about acute disruptions to the reassuring status quo. Critical trauma studies is, now, a still-evolving product of twentieth-century movements and ideas, including structural functionalism, psychoanalysis and its interlocutors, postmodernism and poststructuralism, the constellation of theories/methods/interventions known as “identity politics,” the turn to affect, critical body studies, critical race theory, and the new materialism.

Extending and challenging the focus on psychic breaks and cultural representations and interpretations, the material body is not absent from the imaginings of critical trauma studies. Indeed, the body has always been present if not fully theorized, its material insistence grappled with through investigations of somatic ruptures, such as railroad accidents and traumatic brain injury (Stevens, this volume [chapter 2]; Malabou 2012; Morrison and Casper 2012). The centrality of the brain to considerations (and treatments) of trauma has fostered new scholarly directions that attempt to link neuroscience with cultural analysis. The brain is understood to be “plastic” and thus responsive to interventions, accidental or deliberate. The amygdala has long been a key site for investigations of trauma, connecting as it does to emotion and memory, and “trauma” is now recognized as capable of altering the brain’s structure and function. An important task for critical trauma studies is to learn from and make use of these neuroscientific “findings,” while also interrogating how neuro-stories are rapidly becoming hegemonic explanations and depictions of human life (Rose and Abi-Rached 2013).

This book follows from the many iterations of critical trauma studies that have come before, but we are especially indebted to what Maurice Stevens (2014) calls critical trauma theory. Here, the category of trauma is not taken for granted, but rather unraveled and interrogated to assess the political and cultural work that “trauma” does—both in the world, as well as for those (like us) doing the interrogating. Stevens writes, “Is there something particular or different about the contemporary moment that calls us to reflect upon injury and trauma in new ways? In the forms of mass labor exploitation, proliferating military conflict zones, industrial catastrophe, natural disasters, state austerity plans, and ecological system collapse, the past decade has given evidence of increasing harm being experienced by most of the world’s population.” In this way, Stevens draws attention to both the epistemological and broader geopolitical contexts in which critical trauma studies is unfolding.

That we are increasingly living in an “age of trauma” (Miller and Tougaw 2002)—that is, that the register of trauma is ever more frequently employed to account for understandings of ourselves, our actions, and the things that are done to us (and that we do to others)—invites consideration and, inevitably, intervention. We suggest that a popular imperative to frame both everyday and spectacular experiences alike as “traumatic” imbues an ethical component into critical trauma studies that must be named, considered, and worked through. There are high stakes not only in studying how and why people are injured, but in assessing, articulating, and even challenging hegemonic modes of diagnosis, rehabilitation, recovery, and redemption. The conceptual spine of this book—embedded within the glue that binds the pages—is that critical trauma studies invokes an ethics of intellectual and moral engagement.

Whereas clinical and psychological perspectives respond to trauma as a psychic and/or embodied marker of disruptive experience, a critical approach attends to the ways that the category of “trauma” reveals and unsettles social and cultural classification systems, including how we triage subjects for “help” and intervention (Simmons and Casper 2012; Jackson, this volume [chapter 12]). Indeed, we would argue that twenty-first-century humanities, following on the heels of large-scale disruptions of the twentieth century, are broadly and locally constituted by the study of trauma itself. “Trauma” offers an “imminent” god, as it were, in which the humanities live and breath through the practices and needs of people at the edges—of space, time, and subjectivity—moving forth and back through various borderlands. As a set of intellectual ideas about ruptures in lived experience and transformations of self and being, critical trauma studies engages fundamental questions about our relationships with one another, the “natural” world, and other species (Casper 2014), with events, and with the very terms of our existence. Investigations of trauma are thus both ontological and epistemological, assemblages and intersectionalities, modes of being and ways of knowing.

Thinking and Doing

Critical Trauma Studies is the product of our individual and collective attempts to build on recent work in the field with the explicit goal of linking the domains typically understood as “theory” and “practice.” That is, we wanted to put “thinking” alongside “doing” in fresh and provocative ways. Many works have taken up trauma studies and trauma theory, and many have focused on the “doing” of trauma care (the “how-to” and “self-help” genres; see Berns 2011). Seeking to query and bridge this divide, we were motivated by a sense of obligation to find work that would challenge the tired canard that the humanities, supposedly “unmarketable” disciplines, have become irrelevant. In fact, we would instead suggest that we need ever more innovative and atypical convergences of the academic humanities and social sciences with their panoply of practical uses and inspirations.

This volume thus brings together those who think and write critically about trauma with those who work with people who suffer traumatic events, recognizing that sometimes these groups are the same. That is, the trauma theorist may also have been traumatized, and may also work as a “fixer” of trauma in some other domain, and may also interweave these varied experiences in and through her own practices. Subjectivities and practices are multiple. The essays in this volume show that it is precisely within disruptive moments of wounding and their aftermath that human bodies and subjectivities—and, indeed, families, communities, and nations—become targets for inscription of the always-shifting but deeply divisive categories of normal and pathological (Canguilhem [1966] 1991), and of designations of affliction and appropriate healing.

It is not the case, we believe, that trauma practice is simply an applied version of critical trauma studies. Rather, the ethical and epistemological aims of each domain are different and overlapping. In one, scholars are invested in critically engaging “trauma” as an object of analysis, holding it up to the light, as it were, to examine its interior scaffolding, and often conceptually divorcing it from its deployment as an experience or diagnostic category. Trauma practitioners, on the other hand, are obligated to engage trauma somewhat less critically, and as it actually presents in the clinic, the psychiatric space, the shelter, the prison, the body. As many of us engage in both critical trauma theory and trauma work (for example, human rights, counseling, pedagogy, ministry, advocacy), simultaneously and often uncomfortably, we are called to a specific kind of reflexivity. This self-conscious practice offers a way of paying attention to the power dynamics, subjectivities, and meanings invoked in our individual and collective research, writing, and activism about trauma.

As editors, our attempts to see light in the friction between practice and theory are focused by a degree of hopefulness in the face of postmodern skepticism about the integrity of the subject and the ways that subjects are always already assumed to be healthy and whole, or are able to be made so via the classic trauma and recovery narrative. While shaped by and invested in critical trauma theory, this volume is deeply concerned with issues of “practice.” We attend analytically to the trauma apparatus while recognizing that we do so fully within it. We also recognize it may be possible to discern the theorizing that emerges through practice itself, including the workings of the body (e.g., Siebers 2008; Moore and Casper 2014). If, as Stevens (this volume [chapter 2]) notes, “trauma is as trauma does,” then we are firmly entangled within being and doing, living and interpreting, memory and hope, and all points in between.

Mapping the Collection

Critical Trauma Studies is organized around three interwoven themes: politics, poetics, and praxis. Yet these categories are more than a way to “sort out” the book’s contents for our readers. Current work on trauma is richly invested in political strategies and operations, in questions of language and representation, and in “grassroots” concerns with how trauma and its interventions are enacted and responded to. The book’s chapters take up, embody, and interrogate each of these imbricated themes, with varying degrees of emphasis: some foreground biopolitical traces and processes, while others listen more assiduously to language (including its absence), and still others build narratives from the ground up, heeding lived experiences. In our view, these are the major conceptual and practical spaces at and through which critical trauma studies is unfolding at this particular moment.

Each contributor to this volume is a subject of traumatization, in an active sense of the term that is cognizant of trauma’s (and the study of trauma’s) subject-making features. The volume is deliberately “book-ended” with provocative essays by scholar Maurice Stevens and novelist Dorothy Allison, each deeply engaged with trauma, experience, and language but from quite different approaches. Both dare to articulate the investiture of language and narrative and their vital necessity in critical trauma studies—while simultaneously embracing the instability and inadequacy of text. They frame our collection because they make no apologies for gaps and poststructuralist destabilizations. They also, in different voices, tell it like it is. Practice and theory go on together, in spite of and because of all that, in the work of politics and praxis. Conjoined with the other essays in this collection, these offerings show how feeling, knowledge, practices, and power are mutually constitutive and profoundly political.

And so, in “Trauma Is as Trauma Does: The Politics of Affect in Catastrophic Times,” Stevens sets the tone for our collective dialogue with intellectual depth, generosity, and creative critique. Working from within a comparative studies tradition, attentive to history, language, affect, and politics, Stevens locates trauma as a biopolitical apparatus rather than “simply” an experience or category per se. He focuses on the affective economies of trauma, how the concept of “trauma” works in both productive and limiting ways. For Stevens, the term “trauma” is invoked when subjectivity, assumed to be rational and ordered, has been destabilized. But in relying on trauma as a diagnostic category, we also reproduce the apparatus of trauma. This may constrain the kinds of “posttrauma” reactions (individual and collective) that ensue and also preclude other kinds of openings and avenues for social action. Trauma, in this framing, is interwoven into a key part of a control society. As Stevens reminds us, we need to pay attention not just to what trauma does, but how it does as well—especially among those “drawn to the glow of its inchoate affect.”

Legal scholar Francine Banner globalizes the trauma apparatus, offering a harrowing account of Chechen women suicide bombers. She suggests that geopolitical trauma produced by the Russo-Chechen conflict was expressed in the embodied subjectivity of the bombers. Interrogating both ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Within Trauma: An Introduction

- I. Politics

- II. Poetics

- III. Praxis

- Bibliography

- About the Contributors

- Index