![]()

1

Introduction

Crime, History, Science

The Van Nest murder case of 1846, while unique in its tragic details, illustrates many of the issues typically raised by biological explanations of crime. The killings occurred in an isolated farmhouse on the shore of one of New York’s Finger Lakes, on a March evening just as the seven members of the Van Nest family and their hired man retired to bed. Someone slipped into the house and butchered the farmer, his pregnant wife, his elderly mother-in-law, and his two-year-old son, whose small body was eviscerated by the knife, leaving several feet of intestines dangling from the wound. Within days, the authorities arrested William Freeman, a man in his early twenties of African and Native American descent. Freeman confessed to the massacre, although he was never able to clearly explain why he had singled out the Van Nests. At times, he suggested that he had been revenging himself for an earlier wrongful imprisonment (a case in which none of the Van Nests had been involved) and at others that he “had no reason at all.”1

While William Freeman was still in his teens, he had been sentenced to five years in prison for horse theft—a crime for which he was evidently framed by the actual thief, a far more sophisticated man. In any case, Freeman maintained his innocence, and as he served his time in New York State’s formidable Auburn Prison, he became increasingly bitter about the conviction, especially as he was cruelly flogged for rule infractions. But he showed no signs of mental peculiarity until after an altercation with one of the prison’s keepers. When ordered to strip for a flogging, Freeman instead attacked the keeper, who struck back, hitting the prisoner so hard on the head with a wooden plank that the board split. From then on, Freeman suffered from deafness and an inability to think clearly. He deteriorated mentally to the point of becoming (one eyewitness reported) “a being of very low, degraded intellect, hardly above a brute.”2 On release, Freeman sought the arrest of the people who had had him locked up; when he got nowhere with that approach, he started planning another sort of revenge. His determination to right his wrongs may have come to include the Van Nests because when he sought work at their homestead shortly before the massacre, the farmer had declined to hire him.

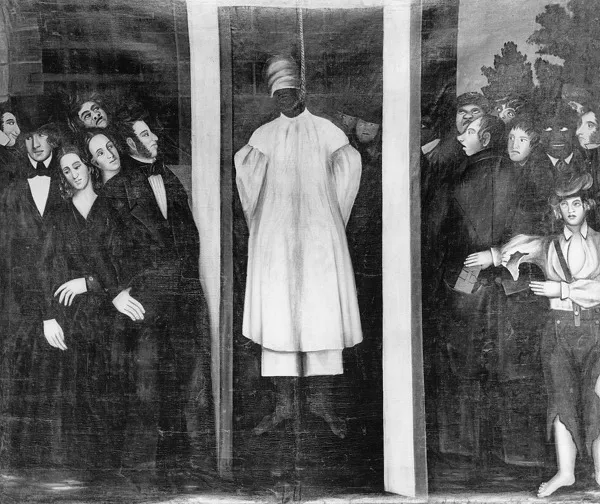

Freeman’s arrest triggered a ferocious debate that became typical of cases in which an appalling crime is attributed to biological abnormality. In the majority were the local citizens who initially tried to lynch Freeman and then demanded that he be legally hanged. These included members of a first jury, which determined that Freeman was “sufficiently sane in mind and memory, to distinguish between right and wrong,”3 and of a second jury, which found him guilty of the crime. “Many of the voices that screamed for retribution,” writes Andrew Arpey in his book on the Freeman case, “did not hesitate to cite the killer’s race as a source of his depravity.” The other side included a local clergyman, who, observing that the community treated its black population as outcasts, asked, “Is not society in some degree, accountable for this sad catastrophe?” Freeman’s brother-in-law agreed, claiming that white men’s mistreatment turned his people into “brute beasts.”4 A former New York State governor, William H. Seward, and his law partners volunteered to defend Freeman, arguing before the two juries that the prisoner was insane (“unable to deduce the simplest conclusion from the plainest premises”)5 and thus not responsible. Seward managed to get a stay of execution and, eventually, an order for a new trial, for which he enlisted the assistance of a number of physicians and psychiatrists, including Dr. Amariah Brigham, superintendent of the local lunatic asylum and one of the country’s leading authorities on insanity. But Freeman, having declined mentally to the point of idiocy, died before the new trial began. In the autopsy report, Brigham wrote that he had seldom seen such extensive brain disease.6

In Freeman’s case, biological abnormality was offered not as an account for criminal behavior in general but as an explanation for Freeman’s particular offenses. Shortly after the Van Nest murders, a local newspaper editor, speculating on the rumor that a relative of Freeman’s had been executed for murder six years earlier, reasoned that there “must be some bad blood running in the veins of the Freeman tribe,”7 a conclusion that seemed to him especially compelling in view of the killer’s Indian (and therefore presumably violence-prone) ancestry. Unlike later biological theorists, the editor did not try to claim that crime in general is caused by a biological factor such as “bad blood.” However, the case in its broad contours, resembled many others that preceded and followed it in the history of biological theories of crime: a crime or sometimes series of crimes that seemed monstrous and inexplicable; a mentally disordered defendant; medical and legal specialists who were confident that mental abnormality had caused the criminal behavior; and a philosophical tension between free will and determinism. Moreover, the Freeman case became a focal point for issues of criminal responsibility and punishment that were coming to a head in the broader community, and in this respect, too, it was typical of notorious cases in which a novel biological defense is attempted for the first time.

Among those issues, most influential was an intensifying debate over proposals to eliminate capital punishment. Abolitionists held that Christians should practice forgiveness, while retentionists fought back with biblical exhortations for retribution. Opinions were further inflamed by a growing debate over the insanity defense: Should insanity be defined in terms of severe mental illness or the more stringent requirement that the defendant had at the time of the offense been totally incapable of distinguishing right from wrong? (If the latter standard were used, Seward grumbled, the insanity defense could never be used, for it would require a “complete obliteration” of memory, attention, and reason of which “the human mind is not capable.”)8 Should courts allow a defense based on the new diagnostic category of moral insanity, according to which a person can be ethically insane while normal in other mental functions? And how should insanity be determined? The latter was a particularly hot issue for those who suspected that Freeman was feigning madness.

Related was a debate over court leniency and its effects. In the view of some members of the Auburn community, an acquittal by reason of insanity in a case immediately preceding the Van Nest murders probably encouraged Freeman to think he could get away with murder. Another such acquittal would foster more violence. Here the opposition countered that it was legal harshness that had sent the innocent young man to prison for horse theft in the first place and that had led, ultimately, to the Van Nest killings. Further exacerbating feelings about the Freeman case was a growing debate over the causes of human action. Is criminal behavior determined by social and biological factors beyond the individual’s control, as the popular science of phrenology was then teaching, or do humans freely choose their courses of action? The Freeman trial, then, played out in the context of heated arguments over major social issues such as capital punishment, the insanity defense, the appropriate degree of severity in criminal punishments, and the causes of criminal behavior.9 Politically, legally, and racially, the case raised contentious issues, pitting medicine against law, religion against science.

There have been periods in which biological theories aroused strong resistance, as Brigham’s and Seward’s explanations did in mid-19th-century New York, but at other times biological theories have enjoyed easy acceptance. Just twenty-five years after William Freeman’s trials, for example, Americans were far more receptive to biological explanations of crime, and in the early 20th century, the feeblemindedness or weak intelligence explanation of crime became almost instantly popular, a kind of fad. But today, efforts to explain criminality in terms of what the sociologist Nikolas Rose terms the “biology of culpability” once again arouse strong reactions.10

Currently, liberals tend to view biological theories as efforts to shift responsibility away from social factors that cause crime and onto criminal individuals. Conservatives embrace biological theories more enthusiastically but grow uneasy when one speaks (as I do throughout this book) of their history, a perspective suggesting that scientific truths are contingent upon social factors. Sociologists look askance at the identification of biological “risk” factors and other indications that social influences do not fully explain crime. On the other hand, biocriminologists—meaning those who produce biological theories of crime11—tend to dismiss sociological and historical analyses as a distraction from the important work of scientific research. The political fault lines have shifted since the mid-19th century, when the liberal faction, including Seward and Brigham, proposed the biological explanation; but the polarization itself recurs, and today’s issues remain much the same as they were when William Freeman sat, bewildered, in the prisoner’s dock.

These issues resurfaced in the case of Andrea Kennedy Yates, the Houston, Texas, woman who in 2001 systematically drowned her five children in a bathtub. Yates had been a bright, athletic student, and she had worked as a nurse until 1993, when she married Rusty Yates, became pregnant six times in seven years (one pregnancy ended in a miscarriage), and adopted Rusty’s evangelical religion. Rusty insisted that she homeschool the children and take full care of them herself (part of the time the family lived in a former bus), circumstances that placed heavy burdens on Andrea and isolated her from social support. One of her few close friends was a religious extremist who taught that “the role of women is derived from the sin of Eve.”12 Andrea deteriorated mentally after each pregnancy, attempting suicide, hallucinating, mutilating herself, denying the children food. When her father (for whom she had also been caring) died in 2001, she became catatonic. A doctor prescribed antipsychotic drugs but warned the couple that they should have no more children, given that childbirth triggered Andrea’s most severe mental problems. They ignored his advice, however, and after Andrea gave birth to their last child, she went into postpartum psychosis (a condition far more severe than postpartum depression). She confessed immediately after drowning the children, explaining that she was not a good mother, that the children were not developing correctly, and that she was possessed by Satan.13

In her first trial, Andrea Yates was found guilty of capital murder and sentenced to life in prison. The jury rejected the defense argument that postpartum psychosis made it impossible for her to tell right from wrong, reasoning that she would not have phoned the police immediately after the killings, or attributed them to Satan, had she not recognized the evil of her action. Rusty divorced her and remarried. But the case reopened in 2005 when it was discovered that a prosecution witness had given false testimony. On retrial, a jury found Yates not guilty by reason of insanity, deciding that due to postpartum psychosis she had in fact not known right from wrong when she killed the children. As a result, she is now incarcerated in a mental hospital rather than a prison.

Many of the same factors that had galvanized the public in the Freeman case did so again during Andrea Yates’s trials: the atrocious and inexplicable nature of the crimes, the multiple victims and the fact that they included an infant, the mentally disordered defendant, and the relative novelty of the defense. Vituperative Internet postings testified to the way this case, too, tapped into the hot-button issues of the day. The columnist Mona Charen felt that Rusty should also have been put on trial: “The word negligent doesn’t even begin to describe his malfeasance. How is it possible that a man who knows his wife’s sanity has been compromised by childbirth can nonetheless impregnate her five more times . . . ? How could he leave her alone when he knew she was, at the very least, suicidal?”14 Others were outraged by what they saw as the court’s leniency: “If she does not merit an IV in the death chamber, no one does.”15 Once again, factors in the social context help explain such inflamed anger—in this case, evangelicalism; debates over women’s proper roles; the still-rankling memory of John Hinkley’s successful insanity defense after he tried to kill President Ronald Reagan; and the unfamiliarity of the postpartum psychosis defense.

While there is currently a good deal of resistance to biological explanations of crime, that opposition has started to crumble. Such hostility is often strongest when new biological theories are first proposed, shaking up tried-and-true ways of thinking about crime. But when a new theory resonates with other culturally dominant factors, as current genetic, evolutionary, and neurological explanations do, opponents often come around. We seem to be on the threshold of a major shift that could lead to various genetic and other biological “solutions” to criminal behavior.16 Whether or not the shift leads to a brave-new-world scenario in which, say, babies’ genes are inspected for criminogenic risk factors depends on how we decide to shape our future. And that, in turn, depends on how well informed we are about the past and present biological theories of crime.

Why Bother with Biocriminology?

Biological theories raise profound and inescapable issues about the nature of justice. If William Freeman had been hanged, would an innocent man have been executed? Had he been sent to Brigham’s Utica State Lunatic Asylum, would justice have been achieved, or would the Van Nest victims have gone unavenged? Which of the two Andrea Yates juries got it right—the one that found her guilty or the one that acquitted her? If some crimes are indeed biological in origin, then it is impossible to achieve justice or to improve crime prevention without grasping the nature of such causes. And yet few ideas are more dangerous than that of innate criminality, which has long been associated with eugenics, the science that promises to eradicate social problems by cleansing the gene pool. In the past, eugenic solutions have led to sterilizations, life imprisonment to prevent reproduction, and (in the Nazi instance) wholesale executions of mere suspects in minor crimes.

No one today advocates executing people with allegedly criminogenic genes, but less draconian forms of eugenics continue to find advocates. The former U.S. education secretary William Bennett has remarked, “If you w...