![]()

Part I

Pride Then

![]()

1

From “Gay Is Good” to “Unapologetically Gay”

Pride Beginnings

The first march was very much in keeping with how I saw myself politically. Something new and unique to my experience. It was unique because this was the first time in my life that I marched for myself. I marched for my freedom, I wasn’t marching as an advocate for someone else’s freedom, civil rights for instance—that was uniquely different. That I saw that my identity as a gay man was worthy of political formulation, worthy of a march up an avenue in America in 1970, so that was unique, and I saw progression in terms of my own development, in terms of how I saw human rights and the rights of people, so that was uniquely different.

—Steven F. Dansky, marcher at Christopher Street Liberation Day, 1970

In 1970, Steven F. Dansky was no stranger to activism.1 A young, progressive man living in New York City, he had marched for civil rights, women’s liberation, and economic justice. For the past year, he had been an active member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a radical group committed to broad social change with gay rights at its core. For Dansky, with his activist background, the Christopher Street Liberation Day (CSLD) march in New York City—also known as the first Pride parade—could have been just another protest, complete with angry chants and fists in the air. Instead, Dansky described the march as “something new and unique to [his] experience” because for the first time, his identity as a gay man took center stage and was “worthy of a march up an avenue in America.” In contrast to when he marched for the rights of African Americans, women, or the poor, this time he marched for himself, for his own identity. And unlike the past year’s activism with GLF, at CSLD, Dansky was part of a grand gathering of gays and lesbians, who by their sheer numbers made a bigger, bolder statement than GLF had been able to make in their smaller demonstrations. Moreover, Dansky and his fellow participants made their statement in a new way, by having fun and celebrating their identities.

On the other side of the country in Los Angeles, Pat Rocco was not exactly what you would call an activist—he was more fabulous than that. As a performer and filmmaker, Rocco was prominent in the gay social scene of the late 1960s and 1970s, which made him a leader in the gay community. When other community leaders organized Christopher Street West (CSW)—a parallel event to be held simultaneously with CSLD in New York City—Rocco got on the phone and reached out to everyone he knew, urging them to go to the parade. He and his creative friends brought a new brand of activism to the event by celebrating gay identity with a grand parade in West Hollywood. The events in New York City and Los Angeles looked different, but had the same central purpose: proclaiming the cultural worth and dignity of gays and lesbians.2 These events also had the same pitfalls as the others. Lesbians and people of color struggled to be fully included and some in the community criticized Pride’s celebratory nature as a distraction from the seriousness of gay oppression.

I talked to Steven F. Dansky, Pat Rocco, and nine other women and men who marched in the first events of what came to be known to the world as “Pride.” Along with a smaller march in Chicago, the events were held on June 28, 1970 and collectively drew roughly five thousand marchers and an equal number of spectators. While Chicago’s event continues as one of the nation’s largest parades today, I focus here on the marches in New York and Los Angeles because they were significantly bigger at the time.3 Drawing on interviews with the pioneers of these first parades, scholarly accounts, and news reports, letters, and editorials published in the leading gay periodical of the time, the Advocate, this chapter tells the story of these first parades. The events commemorated the Stonewall riots of a year before, when patrons of a gay bar in New York City fought back against routine police harassment. These riots galvanized gays and lesbians across the country and motivated them to fight for cultural equality with renewed energy and optimism. Though gay and lesbian activists had begun changing tactics a few years prior, Stonewall marks the symbolic moment in LGBT history when gays and lesbians took to the streets to demand equality without compromise. With festive marches to mark the anniversary of Stonewall a year later in New York City and Los Angeles, gay and lesbian activists pivoted movement activism away from targeting the state and culture in the mind toward targeting culture in the world.

CSLD and CSW were unique in tone as well as message. Instead of an angry march or a solemn vigil, participants staged moving celebrations that, for many, were downright fun. The myriad artists, performers, church members, and social service workers in Los Angeles’s gay and lesbian community, in particular, put on a parade to publicly revel in gay identity. While some believed this open revelry would ultimately hurt the cause of gay cultural equality, many found the demonstration both personally liberating and publicly effective. Participants on both coasts experienced, some for the first time, the thrill of holding hands in public with same-sex partners, while being surrounded by so many others who showed pride in being gay. They also confronted fears of violent backlash at such public displays, fears that were thankfully unrealized. This open celebration of gay identity contested the dominant heteronormative cultural code that interpreted homosexuality as shameful. These inaugural events of what would later evolve into Pride solidified the gay and lesbian movement’s turn toward bolder activism targeting both culture and the state, while also laying the foundation for the grand events—and the controversy that can surround them—that continue today.

Setting the Stage for Pride

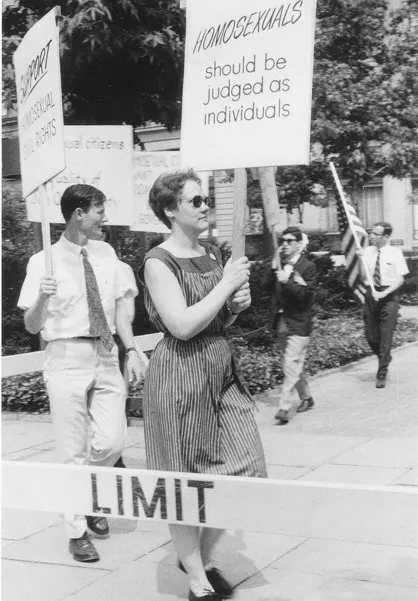

Pride has a little known precursor: the Annual Reminder. On the Fourth of July each year from 1965 to 1969, activists silently picketed Independence Hall in Philadelphia to bring attention to gay rights.4 Participants followed a strict dress code of jackets and ties for men and dresses for women with the intention of presenting themselves as normal, respectable, and non-threatening. They held signs like the one shown in figure 1.1, declaring, “Homosexuals should be judged as individuals.”5 Marching silently, activists sought to change the public perception of gays and lesbians as socially deviant and instead show that they deserved equal treatment by the government and their fellow citizens.

The Annual Reminder was indicative of most gay and lesbian public activism of the time, which pursued narrow political goals and emphasized gays’ similarity with heterosexuals. Demonstrating at sites like Independence Hall, homophile activists, as they were called, drew on American civic values to pressure the state for equal treatment. To show that they deserved equality, activists fought dominant stereotypes of gays and lesbians as perverts and sexual predators entirely at odds with “respectable” society. By dressing in conservative clothing and adopting a solemn demeanor, they presented homosexuality as a small, isolated aspect of identity that did not hinder gays’ ability to be good citizens and neighbors.6 Rather than challenging the heteronormative cultural code of meaning, with its binary gender roles and compulsory heterosexuality, homophile activists stressed that being gay did not mean breaking with traditional femininity or masculinity.7 In this way, activists targeted culture in the mind, asking individuals to change their minds about gays and lesbians and come to regard them as good people worthy of respect. They did not challenge the cultural code in the world that defined homosexuality as inferior to heterosexuality, but instead targeted the individual attitudes that guided people’s treatment of gays and lesbians. Activists hoped that by changing individual attitudes, particularly those belonging to influential professionals, they could bring about change in the state and to the institutional policies that discriminated against gays and lesbians.

Early organizations—such as the Mattachine Society for (mostly) gay men and the Daughters of Bilitis for lesbians—had what may strike the twenty-first-century observer as fairly modest goals: to provide social support outside the bar scene and to educate professionals in the medical and psychological communities about gays and lesbians.8 Both groups drew their names from fairly obscure historical references, signaling the careful approach of their founders.9 With names that masked their identification with homosexuality, groups could organize gays and lesbians under a cloak of safety while still communicating their true purpose to those “in the know.” Homophile activists targeted straight professionals with the logic that if these influential citizens tempered their rhetoric about gays’ inherent sickness, then the mainstream would not see them as a threat to its moral and social order. Scholars describe the homophile movement as “accommodationist” because activists did not challenge negative policies and cultural meanings head on, but rather attempted to forge a safe compromise in which they could live unmolested.10

Homophile activists’ accommodationist strategy was a first attempt at creating a more livable society for gays and lesbians. In the years leading up to CSLD and CSW, gays and lesbians experienced a stark disjuncture between the opportunities afforded by Western society and its cultural and legal censure of homosexuality. By the 1960s, many gays and lesbians in the Western world had the structural ability to organize their lives around their same-sex desires.11 Free of a social structure that required close family connections for economic survival, gays and lesbians (as well as countless straight people desiring an alternative to the traditional relationship model) could pursue the sexual and romantic relationships that they wanted. Though possible, such a path was not easy. The heteronormative cultural code was (and still is) a set of meanings that interprets heterosexuality as both natural and good. Without an accompanying code of tolerance, as the one we see today, gays and lesbians were widely condemned by clergy, health professionals, and politicians alike as abnormal and even dangerous to society. Gays and lesbians appeared in the public eye only through stereotyped images as effeminate, sex-crazed men or butch, possibly predatory, women.12 Socialized with these cultural meanings, straights and gays alike generally believed that homosexuality was detrimental to individual souls and collective society. Adding to this cultural stigmatization, the American legal system treated homosexuality as an illegal sexual act, making the social lives of gays and lesbians subject to police harassment.13

Thus, as more and more gays and lesbians experienced their homosexuality as a source of personal fulfillment, they faced public messages telling them that it was a moral, psychological, and civic failing. Many believed these messages, understanding themselves as essentially damaged but knowing that change was impossible. In seeking accommodation, homophile activists hoped to reduce some of the cultural and legal sanctions faced by gays and lesbians. At the same time, they built extensive communication networks through which gays and lesbians shared their visions for a culture in which they could live openly and proudly. Though many put on a mask of heterosexuality in their daily lives—a strategy that today we would call being “in the closet”—they increasingly saw as possible a day when they could take off this mask.14 Homophile organizations worked to connect gays and lesbians with one another through newsletters and social events, thus providing spaces where they could experience their sexuality as a positive, socially affirmed identity.15 Meanwhile, these formal organizations were not the only game in town, as gay and lesbian bars flourished in San Francisco, New York, and other large and even small cities.16 Bars drew working-class and gender-transgressive gays and lesbians who were marginalized both by larger society and by the middle-class homophile movement. There, too, gays and lesbians came together, as their desire grew for a society in which they could live openly, feeling proud instead of ashamed of their sexuality.17

During the 1960s, many gays and lesbians like Steven F. Dansky were active in the civil rights and women’s movements. They gained both inspiration and practical training in mobilization, movement organization, and protest tactics from these experiences, learning to fight back against social oppression. Meanwhile, growing out of New Left ideology that traced racial, gender, and class inequality to cultural roots, gay liberation ideology identified heteronormativity, not same-sex desires, as the cause of gay and lesbian oppression. Rather than a source of difference and even inferiority, gay liberationists saw homosexuality as a powerful challenge to restrictive Western culture. Heteronormative culture and attendant institutions like marriage and the traditional family, they claimed, repressed everyone, straight and gay alike, by allowing only a narrow range of sexual and gender expression.18 By pursuing same-sex relationships and playing with gender roles, gays and lesbians broke with this repressive culture and could thus lead the way in its cultural overthrow. Taking up the New Left’s emphasis on the psychological damage brought on by repressive culture, gay liberationists promoted pride in one’s gay identity as personally fulfilling. The act of “coming out” publicly as gay or lesbian thus took on both personal and political dimensions.19 With the lofty goal of cultural upheaval, gay liberation ideology nonetheless had a lighter side by emphasizing the pursuit of pleasure.20 To be truly free, liberationists argued, individuals needed to be allowed to have fun in whatever way suited them without risk of sanction from the state or the culture.

For gay liberationists, the source of gay and lesbian inequality was not their exclusion from institutions or discriminatory laws, but rather a culture in the world that prescribed rigid norms and underlay state and institutional inequality.21 Gay liberation ideology quickly developed into two branches: gay power favored working in coalition with other marginalized groups for a broad attack on oppressive powers, while gay pride focused on bolstering the public visibility of gays and lesbians. In the following chapter, I detail how this split led to conflicts between Pride participants as the phenomenon grew. For now, though, gay liberation ideology served as a cultural resource that emboldened gays and lesbians to demand profound social change. Thus, by 1969, many gays and lesbians had both the cultural and material resources with which to challenge their cultural inequality in a new way.22

The influences of gay liberation ideology and 1960s civil rights activism came together in the slogan, “Gay Is Good,” coined in 1968 by veteran activist Frank Kameny. Inspired by Stokely Carmichael’s “Black is Beautiful,” “Gay Is Good” similarly sought to reclaim a long-denigrated term by associating it with positive qualities. In line with gay liberation ideology, the new slogan called on culture in the world to change by adopting a new meaning of homosexuality. And like civil righ...