![]()

1

Un Tipo Típico

Alvarez Guedes Takes the Stage

I don’t remember when I heard my first joke by Cuban exile comedian Guillermo Alvarez Guedes. His comedy has always been in my life, hiding in plain sight. I came to this realization early on in graduate school when I sat down to write a seminar paper on exile humor and decided to listen to all of his albums. It was then that I realized that my father, one of the funniest people I know, had been cracking Alvarez Guedes’s jokes for years without much in the way of citation—a practice his son will not duplicate in the chapters to come. I didn’t grow up with Alvarez Guedes albums in my house. They didn’t play in the background of family parties, or on long car rides as so many others have told me anecdotally. His radio show in Miami didn’t reach my home in New Jersey. Yet there he was the whole time, appearing in the joke repertoire of family and friends.

As I show in the introduction, there are many examples of diversión from those early years of the Cuban exile community that I could have addressed in this first chapter: the lively theater scene, tabloid satirical newspapers like Zig-Zag Libre and Chispa, or folkloric events like Añorada Cuba. But Alvarez Guedes is truly the only way a book focused on ludic popular culture in the Cuban diaspora can start. What made him so unique was his durability and popularity across multiple generations of the diaspora over a career that spanned over half a century. Best known for his standup comedy, Alvarez Guedes released thirty-two live albums from the 1970s through the early 2000s. These recordings continue to serve as Cuban social and cultural capital. How many times have I heard someone say, “That reminds me of an Alvarez Guedes joke” and then break out into his or her best rendition? The embeddedness of his jokes is so pronounced that I have even heard people use snippets of his material like “tú eres como el tipo del gato” as a kind of metaphoric shorthand to describe a person or situation—in this case a pessimist.1 This popularity extends beyond his rank and file audience to other professional comedians on and off the island. Every single artist I write about in this book cites him as a vital influence. Starting with Alvarez Guedes, then, also provides a useful point of departure for thinking through genealogies of diversión in the Cuban diaspora.

Though his influence reverberates across generations, this chapter takes a much more focused approach through an examination of his comedy in the 1970s and 1980s. Even then, in those early years of his career in exile, Alvarez Guedes was looked upon as a kind of model exile subject. His standing among the community is best summed up in an article written by Cristina Saralegui for El Miami Herald in 1976, years before she built her talk-show empire: “Ahora, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes es EL TIPICO CUBANO EXILIADO (Now, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes is THE TYPICAL CUBAN EXILE).2 Alvarez Guedes’s status as un tipo típico—a Cuban everyman—is partially due to his politics, which were in many ways in tune with what Lisandro Pérez has called the “exile ideology.” Its characteristics include continuing to attach importance to politics in Cuba; hostility against the Cuban government; conservative, Republican political views; and general intolerance for those whose perspectives on Cuba differ.3 Informing what it meant to be Cuban off the island, this ideology manifested itself in a “behavioral repertoire … ranging from supporting right-wing candidates to opposing publicly anyone voicing sympathy for the Cuban regime.”4 Not content to limit his anti-communist humor to Miami, Alvarez Guedes travelled to Nicaragua to perform a set for the Contras in 1986.5

These politics informed Alvarez Guedes’s larger performance of exile cubanía—a Cuban cultural identity inflected with the politics of the exile ideology. But that was not enough to make him un tipo típico. More importantly, Alvarez Guedes reflected back what his audience wanted to see in itself: a wise-cracking anti-communist with a magnetic affability who could take the turbulence of exile politics and life in Miami and use it as fodder for diversión. Perhaps more than any other Cuban exile artist, Alvarez Guedes insisted upon a ludic sociability that cohered around a narrative of proud, pleasurable exile cubanía mediated through his humor. My research has yet to turn up a negative review of his work. In fact, I argue that people wanted to like him and what his humor represented—an almost utopic narrative of a united exile community that people wanted to believe was possible. His stories about “nosotros, los cubanos” (we, the Cubans) were narratives of unity around a broad notion of cubanía and anti-Castro politics, which served as a distraction from the very real tensions within the exile community. Old grudges from Cuba, past and present political affiliations, and disagreements about how best to bring about change on the island were some of the issues that divided the community from within.6 Disagreement and even violence among exiles convinced of their views as the best way forward for “liberating” Cuba were common. Alvarez Guedes’s albums emphasized common ground through hostility toward Castro, shared Cuban cultural characteristics, Cuban-Anglo relations in Miami, and the manner for engaging these topics through the recognizable codes of Cuban speech and humor. In short, Alvarez Guedes’s performances and persona were powerful interlocking sites of identification for Cubans looking to affirm their cultural identities outside the island in a way that put aside the tensions inside the exile community in a Miami plagued by drug wars, a slumping economy, and anti-Cuban sentiment in the 1970s and 1980s.

Far from simply serving as a cathartic release from the tensions roiling Cuban Miami, Alvarez Guedes’s performances illustrate the role of diversión in forging a narrative of Cuban exile identity that privileged whiteness and heteronormativity while simultaneously speaking back to discrimination from Anglo Miamians. It is in the messiness of popular culture, the way a derogatory joke about blacks can exist on the same album criticizing discrimination against Cubans, that we get at the contradictions that structure quotidian life. But before jumping into my close listenings of the material, more background on Alvarez Guedes’s performance practice is necessary to understand why he has been such an important figure in the history of Cuban diasporic popular culture.

Alvarez Guedes, “The Natural”

Alvarez Guedes was a mainstay in exile entertainment for decades. He released over thirty-two standup comedy albums, published joke books and novels, and produced and starred in a number of television and film projects.7 He co-founded a label called GEMA Records, which released the music of celebrated artists and groups such as Bebo Valdés, El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, Celeste Mendoza, Elena Burke, and Chico O’Farrill. When Alvarez Guedes died in 2013 at the age of eighty-six, tributes and commemorations poured in from Cubans across generations on and off the island. Despite having his material outlawed in Cuba, it has always circulated there clandestinely. High-profile personalities, including comedians, took to the Internet to express their admiration. Island-based Cuban dissident blogger Yoani Sánchez tweeted, “Maestro Alvarez Guedes! Know that here we have continued to listen to you, covertly, all this time!”8 In Miami, where the comedian spent most of his life, his death took over the news cycle for days, with bloggers, journalists, and television hosts covering his death and legacy, often through tears.

Although he is generally known for his work in exile, Alvarez Guedes got his start in the entertainment industry as a young man in Cuba. Born in Unión de Reyes, Matanzas in 1927, he made his radio debut in 1949 on programs ranging from dramas to comedies. In 1951, he debuted the character that would make him famous in Cuba, El Borracho (the drunk), on the nation’s nascent television network, CMQ-TV. Shortly after Fidel Castro rose to power in 1959, he left Cuba with his family for cities with large concentrations of Cuban exiles such as New York, Madrid, and Puerto Rico. He lived in Miami from 1961 to 1968 and settled permanently in the city in 1980, though he performed there throughout the 1970s. He began recording his standup albums in 1973.

Alvarez Guedes performed on television, film, and radio throughout his career, but most people know his performances through his live standup albums. All of these recordings essentially follow the same format. Once his trademark music signals his entrance on stage, he goes right into his material, usually by rattling off a succession of quick jokes. Two-thirds of the way into his performance, there is usually a shift from jokes to a story format marked by observational humor related to social and political issues deemed worthy of attention.9 There is hardly ever interaction between Alvarez Guedes and his audience (the Mariel joke mentioned in the introduction is a notable exception), but this does not mean that the audience is passive. There are no laugh tracks on these albums. Listening closely will reveal the running commentary of the audience in between episodic, raucous laughter, with approving phrases voicing agreement (“It’s so true!”) mixing with sounds ranging from high-pitched cackles to deep belly laughs. The albums were recorded in clubs, restaurants, or studios that Alvarez Guedes rented out for that purpose. The audience consisted of people he invited and their friends for a total of about thirty to forty people in all. The result was a profoundly intimate experience for the audience, which in turn is communicated to the listener of the album. The atmospheric applause and laughter audible on more contemporary standup albums is missing here. Instead, the listener can get a feel for the individuality of audience members and their unique-sounding laughs, their particular utterances, and the cadence of their clapping. In the context of the performance, these expressions of joyful approval sound Cuban. The auditory experience of these recordings makes it possible to laugh not only at Alvarez Guedes’s performance but also with members of the audience in a way that heightens the intimacy and pleasure of communal identification that he himself sought to cultivate.

As the description of the recordings above suggests, the album format begs for a consideration of the way the performance sounds. Identification takes place on the auditory level: it includes Alvarez Guedes’s routine, the distinctive musical accompaniment, and the audience’s reactions. For listeners familiar with Cuban speech (dialect, voice inflection, modes of expression) Alvarez Guedes would be instantly recognizable as Cuban without him ever saying so. His use of pauses in his stories, the way he exaggerates the pronunciation of certain words, and the strategic use of repetition contribute to the Cuban feel of the auditory experience. As he begins to speak, it becomes clear to his audience that he is Cuban, someone who has endured a set of historical circumstances around exile similar to what they have experienced. Confident and convincing in his role as un tipo típico, he offsets the precariousness and impotence of the exile condition through the creation of a stable, relaxed, inviting space where his performance functions as a means for negotiating the at times difficult experience of exile through diversión. The pleasures of group identification and playful narrative technique combine to produce a ludic sociability among an audience now comfortable with temporarily suspending its usual defensive positions regarding Cuba and the complexities of exile life.

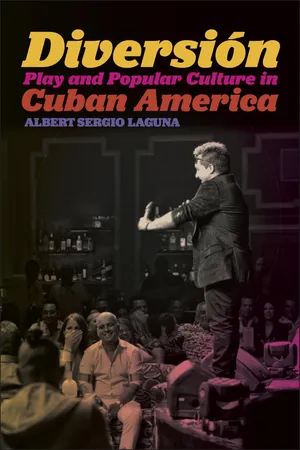

Figure 1.1. Alvarez Guedes performing for audience. Date unknown. Courtesy of Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami.

While his albums and performances quickly became hits among exiles, success did not come immediately for the comedian after leaving the island. In a 2007 interview titled “Guillermo Álvarez Guedes, El Natural,” he describes the difficulty in finding work in the Spanish-language entertainment industry during those early years of exile in the 1960s and 1970s: “To make a living as an actor in those days, you had to be an actor in television soap operas, and to work in television soap operas, you had to have what they called a neutral accent. When they told me that I said, ‘What the hell is a neutral accent? I have a Cuban accent; I don’t know what it means to speak neutrally.’ ”10 This hostility to the entertainment industry’s demand that he tame his tongue created the foundation for his career in exile. Throughout this interview, Alvarez Guedes constantly refers to his commitment to performing “naturally”—a performance practice marked by his use of Cuban vernacular, specifically the corpus of “bad words” that he believed to be authentically Cuban and that lend a quality of “realism” to his artistic production.

The idea of a “natural” cubanía followed Alvarez Guedes throughout his career in exile. His fans and Cuban cultural commentators have long used the term to describe him. Carlos Alberto Montaner, a major voice in the exile community, wrote a short piece published on the back of the Alvarez Guedes 4 album sleeve in celebration of the comedian’s “pasmosa naturalidad” (astonishing naturalness).11 Emilio Ichikawa, journalist and commentator on all things Cuban on and off the island, similarly alludes to the quintessential cubanía of Alvarez Guedes by naming him “nuestro antropólogo mayor” (our great anthropologist), a man who has “penetrated the codes of Cubanity” and who “doesn’t fail to measure the psychophysical temperature of the community.”12 After his death, press coverage echoed sentiments expressed by journalists like Wilfredo Cancio Isla: “Guillermo Alvarez Guedes has died, king of the joke and cubanidad. The man who succeeded in reconciling Cubans everywhere, from the island and the world, through the universal language of laughter.”13

The “naturalness” that commentators have attributed to Alvarez Guedes is due in part to sonic aspects of his performance that I have already mentioned: his accent, tone, and the words ...