![]()

1

The Antebellum Cotton Economy

One spring day in 1844, Friedrich Gerstäcker was floating downriver approaching Shreveport, Louisiana, when he looked toward the left bank of the river “and was not a little astonished when I saw that the left bank of the bayou, right at the point where it merged with the Red River, was covered with snow. Or so it appeared.” After a closer examination, however, Gerstäcker “realized that it was cotton that covered almost an acre of land as densely as snow.” As he continued down the Red and into the Mississippi River, he found himself surrounded by vessels carrying even more cotton downriver to New Orleans. “Wherever my eye gazed, I could see the heavily laden flatboats,” Gerstäcker noted, and he also saw steamboats—once per hour, he estimated, and often three or four at a time—that were “capable of loading three or four thousand bales” of cotton. This cotton was destined for New Orleans, where it was then sold and shipped to points across the globe.1

In the antebellum years, Jewish merchants were on the margins of this booming cotton industry, but three particular developments in this era laid the groundwork for their postbellum success. First, Jewish merchants began to open general and dry goods stores in interior cotton towns. When the traditional cotton factorage system would later break down, these interior general stores would become the most important institutions in the cotton industry. Jewish merchants would thus be in the right place at the right time, facilitating their entry into the cotton industry and their integration into global capitalism. Second, a number of those Jewish merchants accumulated a significant amount of capital during the antebellum years, providing them with the resources to survive the disruption of the Civil War and to enter the postbellum years on sound footing. And third, Jewish merchants began to establish family and ethnic networks that connected partners within firms, brought global investment through New York to the Gulf South, and provided credit to fellow Jewish merchants in the region. These three developments were prerequisites that allowed Jewish merchants’ early toehold in the industry to later blossom into a flourishing ethnic economy.

* * *

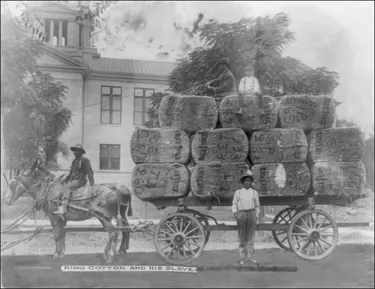

By the mid-nineteenth century the region’s cotton-propelled economy was rapidly taking market share from the Atlantic Seaboard. Yet it doing so on the backs of slaves—between 1820 and 1860, possibly a million slaves were “sold down the river” via an internal slave trade. Predicated upon slavery, the region’s market share increased dramatically to over half of the nation’s crop by 1840. Aggregate value of real and personal property more than doubled in Louisiana over the 1850s as rural landholders poured more and more of their resources into cotton, favoring immediate profit over long-term diversification. And as more land was cultivated for cotton, the steamboat traffic that Gerstäcker had observed on the Mississippi River increased. Between 1840 and 1860, the number increased from 1,500 to 3,500 steamboats, and the amount of freight shipped increased fourfold, from half a million tons to 2 million tons. The value of that cotton increased as well, from $50 million to almost $2 billion.2

Figure 1.1. “Cotton Levee in New Orleans.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-USZ62–4928).

But bringing cotton from the fields to market was no easy proposition. For starters, cotton bales were unwieldy. They often weighed 400–500 pounds each, were four to five feet long, and one to three feet wide, and each bale had to be individually wrapped and then tied. In large part because of their size and weight, damage was frequent. Bales were often “skidded,” dragged across the ground as they were being loaded or unloaded into boats, resulting in dirt on the bottom and thus a reduction in quality. Rain could leave the surfaces of a bale “wet-packed,” caked and foul smelling, similarly reducing quality. While selling crops locally could reduce the time in transit and thus minimize the chance of such damage, shipping to cotton markets such as New Orleans increased risk, but more buyers generally meant higher demand and higher prices. Because the slightest bit of damage could be the difference between profit and loss, the simple act of bringing a bale of cotton to market was critically important and by no means an easy task.3

Figure 1.2. “King Cotton and His Slaves, Greenwood, Mississippi.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-USZ62–36638).

Figure 1.3. “A Cotton Plantation on the Mississippi.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-USZ62–345).

While bringing a bale of cotton to market in good condition was a challenge, so, too, was selling that cotton at the highest price possible. Unaware of the daily fluctuations of cotton prices in an age before the widespread use of the telegraph, interior planters had no way of knowing when the time was right to sell. Cotton prices could change by the minute, often fluctuating 10–15 percent over the course of a month and as much as 30–40 percent over a selling season. But news of those changes could not reach interior planters before the information was out of date. One planter estimated that it took a week for letters to make their way upriver, and another called mail service to Bayou Sara, Louisiana, “extremely irregular.” Thus planters had little idea as to whether they were selling when supply was limited and prices were high or whether they were shipping cotton to a saturated New Orleans market with depressed prices.4

Lacking the requisite knowledge, expertise, and resources, planters frequently turned to cotton factors to market their cotton and maximize their profits. Unlike planters, factors were generally based in port cities, so they weren’t limited to selling cotton locally. Prices differed by market, and factors often had agents overseas—in the large cotton markets of Liverpool, for example. Southern factors often had outlets for their cotton in Northern markets as well, as large Northern firms often had agents located in port cities in the South. Thus factors gave growers access to markets across the globe that they would not have otherwise had.5

In addition to finding the right place to sell, factors also had to find the right time to sell. A stockpile of cotton from the previous growing year could depress prices early in the season, while little prior stock could lead to high early-season prices. If the bulk of the cotton harvest came to market mid-season, prices might be low. However, that could mean a smaller late harvest, which could lead to a spike in prices if demand were high. Or, if demand were low, it could lead to a glut of cotton on the market at the end of the season, lowering prices. It was one thing to rely on gossip when estimating the size and timing of the harvest, but it was another to have the resources and information to make a more educated decision about the best time to sell.6

Sometimes a cotton factor was successful in maximizing profits by choosing the right place and time to sell, but other times he was not. Misreading the market was often the culprit when a factor failed in his task, but so were more nefarious elements. If a factor had cash-flow problems, he might be tempted to sell too soon and before prices had crested, or even more dubious or deceptive business practices might yield a factor more money than was due. In part because planters had so little control over their profits, legal action sometimes followed sales that did not deliver the highest prices of the season.7

In addition to marketing and selling cotton, a factor’s other primary responsibility was to provision planters with the supplies they needed throughout the year. This might include seeds and planting supplies to produce crops, emergency funds to meet an unexpected expense, staple foodstuffs to feed the planter’s family throughout the year, or luxury goods such as books or wine. By provisioning them with goods and supplies while at the same time selling their crop, a factor had an inordinate impact over the lives of the planters and farmers with whom he worked.8

The success of the cotton factorage system was possible only because cotton was the security at the center of the South’s extensive credit system. Factors borrowed money from banks in New Orleans, New York, or Europe and used this money to purchase the goods that they would then advance to planters. Factors also advanced to planters the costs of marketing the cotton, including transportation and insurance against water and fire damage, and charges for weighing and warehousing the cotton once it arrived in the port city. If the cotton was to be sold in another city, factors would advance additional charges for shipping, and potentially charges for recompression, which were often necessary for European shipments. Factors advanced these services, and when the cotton was sold, the cost of the items, as well as the factors’ commissions, would be deducted from the proceeds. Factors would then pay their debts to their creditors and then pay the planters whatever profits—if any—remained. Planters would generally be paid in the wintertime, and the cycle would begin again in the spring.9

This form of credit—security in a crop that was not yet grown and a perpetual cycle of credit and debt—was, in the words of one Northerner visiting Mississippi in 1834, “peculiar.” An 1841 article declared that it was “well known” that, in the cotton trade, “the harvest of one year is, as it were, mortgaged for the expenses of the next.” Such a system, in which money was borrowed against the future crop, was commonplace. “The agriculturalists who create the real wealth of the country are not in daily receipt of money,” noted one observer. “Their produce is ready but once in the year, whereas they buy supplies [on credit] year round.… The whole banking system of the country is based primarily on this bill movement against produce.”10

Cotton crops, however, were not always profitable enough to repay the debts incurred by the planter over the course of the year. Too much sun mid-season could lead to a withered crop, and too much rain could also doom the crop, as could a late-arriving spring, an early frost, or a crop infestation. “Day by day you can see the vegetation of vast fields becoming thinner and thinner,” one contemporary observed, as the result of a worm infestation. “All efforts to arrest their progress or annihilate them prove unavailing. They seem to spring out of the ground, and fall from the clouds.”11

When a bad crop year occurred, a planter’s debts would be carried over from one year to the next. But a bad crop year also placed a factor at risk, as reduced income often meant that he could not repay his own bank loans. To protect against risk, some bankers tried to limit their exposure to three-quarters of the expected revenue from the cotton. Factors also generally lent money to planters at interest and charged a commission on goods purchased or sold on behalf of the planter in order to limit their own risk. In this way, both the bankers and factors could make money while limiting their risk, although they were not always successful in doing so.12

While the factorage system long dominated antebellum mercantile life, the landscape was beginning to shift in the years prior to the Civil War, foreshadowing a major transformation that would reach fruition in the postbellum years and would facilitate Jewish concentration in the industry. In the years prior to the Civil War, factors began to find competition in scores of small general stores that were popping up across the interior—some of which were operated by Jews. As transportation improved and new lands opened for production on the cotton frontier, the number of these towns and stores grew rapidly. In 1840, Louisiana’s number of stores per thousand population ranked second in the nation, and while much of this mercantile activity was centered in New Orleans, one estimate counted almost 600 stores in Louisiana outside of New Orleans. Those numbers only grew over time.13

Interior river towns became particularly important to the cotton industry in the antebellum years—particularly towns located on rivers that provided access to New Orleans. “The place has gone business mad,” one newspaper correspondent wrote of antebellum Shreveport. “There seem to be more stores than residences.” Antebellum Natchez was also an important interior cotton center, in close proximity to cotton plantations and along the Mississippi River for easy access to New Orleans. Natchez’s river port shipped 50,000 bales of cotton in 1860, and mercantile sales approached $2 million.14

Bayou Sara, Louisiana, was another interior river town that played an important role in the cotton industry. Located in West Feliciana Parish on the banks of the Mississippi River, Bayou Sara was the largest port in terms of arrivals and departures between Vicksburg and New Orleans, and it was located in some of the most fertile cotton land in the world. It was the transfer point for freight for the Red and Ouachita Rivers, the landing place of the Ohio River coal fleet, and the terminus of the West Feliciana Railroad, which delivered cotton from the interior and acted much like a tributary of the Mississippi. All of this, according to one census report, meant that it was “a commercial center of greater importance than its size or population would seem to indicate.” Few people, the New Orleans Daily Picayune later noted, “have an idea of the immense business done at this [Bayou Sara] point, in the receiving, forwarding and dry goods business.”15

Bayou Sara’s importance was clear by the beginning of the nineteenth century. “You would be astonished I am sure, if you could spend one week at the Mouth [sic] of Bayou Sarah [sic] at this season of the year … to see the quantity of produce that passes daily to New Orleans,” one resident wrote in 1807 to his cousin who was in the “commercial city” of New York. “As the Rivers break up more northwardly,” he wrote, “the Boats come on loaded with every kind of produce that the upper empire affords or that ingenuity can invent, Flour, corn meal, whiskey and Cider, Pork and Beef, live state fed Beaver, Venison and Mutton Hams, great quantities of bacon, Horses in great numbers … and every thing else that the country affords, o...