![]()

Part I

Prelude, 1933–1934

![]()

1

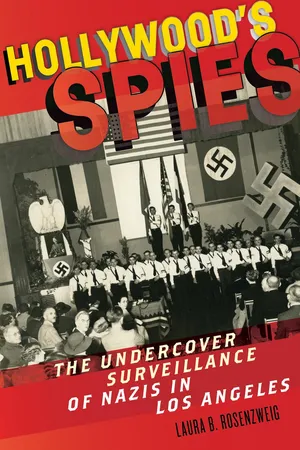

Nazis in Los Angeles

In the spring of 1933, a police report submitted to LAPD captain William “Red” Hynes noted “considerable quantities” of Nazi literature littering the streets of downtown Los Angeles.1 A new group in town, Friends of the New Germany (FNG), was thought to be the source of this sudden burst of Nazi propaganda. Over the next several weeks, Captain Hynes of the LAPD’s Red Squad assigned men to keep an eye on the new group. On August 1, 1933, Hynes sent detective R. A. Wellpott undercover to attend FNG’s second public meeting.2

The meeting was held at 902 South Alvarado Street in a mansion the group had converted into a German American community center, of sorts. It housed an old-style German restaurant, the Alt Heidelberg; a new bookshop, the Aryan Bookstore; and a meeting hall. Approximately one hundred people gathered in the hall for the meeting. Wellpott reported that a makeshift stage was set up in the hall, with a speaker’s podium flanked by an American flag, the imperial German flag, and the Nazi (swastika) flag.3 Fifteen young men dressed in brown shirts, “whose arms bulge with excess power,” were scattered about the hall, “guarding” the meeting.4

The meeting began with a phonograph recording of a German march. The West Coast leader of Friends of the New Germany, Robert Pape, called the meeting to order. Pape presided over a full agenda of speakers, many of whom addressed the audience in German. The first speaker reported on FNG’s first national convention in Chicago, which had concluded just days before. A keynote speaker spoke on “the German-Jewish conflict,” explaining that Nazis wanted to prevent the “bastardization of Germany” by eliminating Jews from power. When several people in the audience jumped up in protest, they were swept out of the meeting by the brown-shirted attendants. The meeting resumed with recorded speeches by Hindenburg and Hitler played on the phonograph. At the end of the evening, the attendees rose and gave the Hitler salute while the new German national anthem was played.5

Friends of the New Germany conducted meetings such as this one in cities across the country during 1933. Nazism had come to America. It was carried here in the hearts and minds of hundreds of Germans who migrated to this country in the wake of the grave economic depression that struck Germany after World War I. Most of these pro-Nazi German immigrants were young, semi- or unskilled men seeking economic opportunity they could not find at home. Disillusioned and displaced, they settled in the United States during the 1920s and waited for der tag, “the day,” when they would return home to a redeemed Germany.6

The ascension of the Nazi Party to power in Germany in 1933, however, changed these émigrés’ plans. Whereas once they viewed themselves as sojourners, they now saw themselves as the vanguard of the international National Socialist movement that would pave the way for the new German empire. In July 1933, forty-five delegates from disparate pro-Nazi cells across the United States convened in Chicago. They formed a new national organization, Der Freunde des Neun Deutschland, Friends of the New Germany.7 Modeled after the Nazi Party, Friends of the New Germany had been blessed by Nazi Party chief Rudolph Hess as the official Nazi Party in the United States.8 The leader of the new group, German national Heinz Spanknoebel, organized the national group into three regions, assigning “gauleiters” (regional leaders) to the Midwest, East Coast, and West Coast to grow the organization into a national movement.9 In accordance with Nazi Party policy, FNG demanded absolute adherence to the Führerprinzip, Nazism’s strict code of obedience. FNG even maintained its own uniformed storm troops to enforce party discipline.10

FNG launched its national political campaign in the summer of 1933. The regional gauleiters went to work recruiting members for the new organization. In cities across the country, FNG distributed pro-Nazi literature and hosted public political lectures to enlist Americans’ support for the Nazi group.11 Meanwhile, Spanknoebel embarked on a national speaking tour to promote the “Hitler revolution” in the United States. Spanknoebel’s speaking engagements primarily attracted German nationals, naturalized Germans, and some German Americans.12 Denouncing international communism and “racial amalgamation,” Spanknoebel defended Germany’s new anti-Jewish policies as self-defense against these intrusive forces. The new Germany was not antisemitic, Spanknoebel explained. Hitler was merely “clean[ing] house” to free the Fatherland of Jewish communists who had corrupted German society. Germans were the real victims, Spanknoebel asserted, not Jews.13

In Los Angeles, FNG’s political activities raised concern among Jewish and non-Jewish groups alike. The Jewish community newspaper B’nai B’rith Messenger (no relationship to the fraternal order of the same name) took notice of Nazi activity in the city in April. An article, “Hitlerites Organize Branch Here,” claimed that Nazi propaganda agents had been sent to Los Angeles by Berlin. The paper even printed the alleged agents’ names and addresses on the front page and called for their immediate deportation.14

In July, forty-six Jewish organizations, including Jewish socialist and communist groups, responded to FNG by calling for a citywide, anti-Nazi demonstration.15 Three thousand people poured into Philharmonic Hall in downtown Los Angeles. Anti-Nazi speakers urged the crowd to remain vigilant against fascism at home and abroad.16 Noted author Lewis Browne, just back from Germany, urged the crowd to use the power of the purse to fight fascism, calling for a boycott of German goods. “When you buy a shoe lace, refuse to take it if it was made in Germany. The Nazis will not last under such economic pressure,” he urged.17 The rally marked the beginning of a twelve-year cycle of protest and counterprotest between Jewish liberal and left-wing groups and the Nazi-influenced right in Los Angeles, as each side jockeyed for the last word in the political struggle.

The Jewish press, the secular press, the Red Squad, local Jewish groups—these were just some of the groups in Los Angeles that viewed Nazi activity in the city with concern. Another group was also watching with concern: the city’s veterans organizations. In the spring and summer of 1933, Friends of the New Germany focused its recruitment efforts on local veterans. FNG leaders assumed that U.S. veterans would flock to join FNG, presuming that U.S. veterans felt just as betrayed by the U.S. government over recent cuts in their veterans’ benefits as they themselves had felt with the Weimar government in Germany at the end of World War I.

Among the first veterans to be approached by FNG officers was the former U.S. Army lieutenant John Schmidt. Schmidt was the perfect potential FNG recruit. Born in Germany in 1879, Schmidt was a career soldier. In his teens, he had served in the German imperial army. In 1900, Schmidt immigrated to the United States and enlisted in the U.S. Army after his naturalization was complete in 1908.18 Even though Schmidt was an American citizen, FNG leaders believed that loyalty was determined by blood, not by the artifice of naturalized citizenship. Schmidt was precisely the type of recruit FNG was hoping to win.

FNG leaders were mistaken. John Schmidt was neither disloyal nor angry. True, Schmidt had been born in Bavaria, and he was a U.S. veteran. Schmidt even had cause to be disillusioned with the U.S. government. Following the war, Schmidt had been hospitalized for six years with what would be considered posttraumatic stress disorder today. He suffered from chronic physical and emotional pain as a result of his military service and in 1930 had lost most of his disability pension when, in the wake of the stock market crash, Congress made sweeping budgetary cuts, which significantly reduced benefits to disabled veterans.19 By 1933, the disabled Schmidt was unemployed and nearly destitute. He wrote heartbreaking personal letters to Leon Lewis, beseeching Lewis to assist him in appealing to Washington to reinstate his pension.20 It took Lewis five years to have Schmidt’s disability pension reinstated. In the meantime, Lewis gave Schmidt money to help him survive. Yes, John Schmidt should have been the perfect recruit for FNG; but he wasn’t. Schmidt was a loyal and patriotic American. He was a member of the Americanism Committee of one of the city’s several veterans organizations, the Disabled American Veterans of the World War (DAV). Schmidt was committed to the nation’s defense, even as he carried the emotional scars, physical disabilities, and financial wounds from his World War I service.

John Schmidt was the first of several DAV veterans who took it upon themselves to investigate Friends of the New Germany. On August 17, 1933, Schmidt went over to FNG headquarters on South Alvarado Street to check out the group. There he met FNG gauleiter Robert Pape, Herman Schwinn, and bookstore coowner Paul Themlitz. Schmidt submitted his first written report on FNG to fellow Americanism Committee member Leon Lewis. Using code name “11” (see appendix 2, “Key to Spy Codes”), Schmidt described what he learned about Friends of the New Germany. FNG’s mission, Schmidt reported, was to fight communism.21 FNG leaders, he said, “show[ed] me plenty of literature proving without a doubt that Communism was part of the Jewish plan of things and that therefore we must all combine to show the Jew as the author of all our troubles in America and throughout the world.”22 Pape told Schmidt that the purpose of FNG was to drive Jews and Catholics out of government in the United States and replace them with German Americans. Pape told Schmidt that he was confident that once in power, German Americans would lead the movement to bring Hitlerism into America.23

Pape was concerned that veterans misunderstood Friends of the New Germany. He told Schmidt that recent resolutions passed by the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and the American Legion denouncing Nazism were misguided and misinformed. FNG was committed to defending Americanism and fighting communists, Pape told Schmidt. FNG wanted to ally with American veterans against their common enemy.24 Pape encouraged Schmidt to bring some of his American Legion and VFW friends to FNG’s next membership meeting to help forge new friendships, and he invited Schmidt to speak at the meeting. Schmidt agreed to both requests.25

Schmidt returned to 902 South Alvarado Street a few days later with his wife, Alyce. They dined at the Alt Heidelberg restaurant. The ambience and the food, Schmidt wrote, were reminiscent of the old country. The Alt Heidelberg was decorated in the style of an old German beer hall. Dinner there was a Depression-era bargain: three courses for sixty cents and beer for a nickel. The restaurant attracted an older German American crowd, but lately, a rowdier, younger crowd of pro-Nazi German nationals had also been frequenting the place.26

During the dinner, Alyce Schmidt got up and left the table to find the powder room. Making her way up the stairs to the second floor of the mansion, she was stopped by a woman who was agitated to find Alyce on the second-floor landing.

“Verboten!” Alyce was told. Alyce turned around and went back downstairs to her table.

Schmidt wrote that he had the distinct impression that there were secrets on the upper floors. “I am sure they have arms and equipment some place. If it is in the house, I will know it soon.”27

Several days later, Schmidt attended his first FNG membership meeting. Herman Schwinn presided. Eighty people were in attendance. The agenda included Schwinn’s report that the German government was making Mein Kampf available in English in the United States, free of charge.28 Schwinn was followed by several speakers, each of whom addressed the audience in German on topics relating to the progress of Hitler and Germany. Then it was Schmidt’s turn to speak. Introducing himself as a German, Schmidt addressed the group in English:

My friends of the old country, I am glad to speak to you though I would not try to make a speech in the German language, as I have been away so long that I have forgotten much of it. I wish to inform you that although I have been [sic] in the American army during the War, I was not overseas fighting against you, b...