![]()

1

Fieldwork in the Mudflats

Balancing six baby horseshoe crabs in my hand, I rotate my wrist to keep them all in my palm. They are wriggling and jostling one another, trying to get some traction on my skin. Taken from their nestled watery mound into my clammy human hands, being held above their home in the dusky sea breeze must be strange. My feet are deep in the muck of the tidal flat, squishing sandy silt between my toes. The late summer sun fades behind me. I feel alive and excited by my fieldwork site. The thrill of being outside with the crabs is invigorating, different from the usual anxiety I feel before an interview with a merely human informant, anxious that any misstep could jeopardize my rapport or entrée. These horseshoe crabs are my reason for being here, I tell myself, but is it just an excuse to enjoy another day at the beach, filthy as this urban shoreline is? I think, feel, and become with the vibrant matter around me—the bubbling of my sinking feet, the tickling of the tiny crab legs, the burn of the sun on my back. I revel in the odors and sounds, the smell of the sulfury tidal flats, the calls of the shore birds, the hum of the Belt Parkway.

* * *

What has drawn me to this beach, month after month, year after year? I have shifted my focus from all things human—body fluids, anatomies, sexuality, interpersonal relationships—to insects and animals—bees, horseshoe crabs. Many friends, colleagues, and family members have asked me why I am researching horseshoe crabs since I am a sociologist, not an ecologist or marine biologist. Sometimes my answers betray my exasperation, and I stumble over my words. I recount the greatest hits of horseshoe crab talents, their capacities, their use in human applications, their exploitation. Yet, over time, I have come to resent the question. I feel as if I am being asked to convince humans that another species can matter and be worthy of concern as either a surrogate or a product for humans. The arrogance of the sentiment “Tell me why you care so I can decide if I care” frustrates me. I want to protest that the foundational “What’s in it for me?” query is the basis for the very human exceptionalism and capitalist consciousness that has gotten us into this environmental mess: global warming, massive species extinction, estrangement, disenchantment, alienation. And then I come back to relative calm, realizing that I must gradually build a case for the horseshoe crab. Just as it was a process for me to understand how an ontologically based interpretation of things can have its own intrinsic value, I must now translate that process for others. Generally, the way to garner that interest, concern, or empathy is to bring it back to the human, the self.

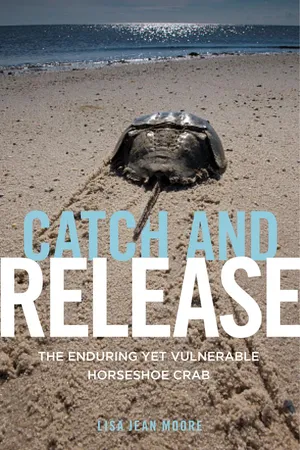

Holding baby horseshoe crabs in the palm of my hand. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.

I have been handling horseshoe crabs since I was a child on the beaches of Long Island, New York. Running down the shore, telson—the tail—in hand, I terrorized my little brother. No compassion toward the crab as it bucked back and forth gesticulating its legs in a desperate attempt to defend itself. Separating amplexed—attached—crabs was also a favorite early summertime activity, and in my youthful stupidity and human hubris I asserted how I was helping the crabs to “stop fighting.” Through endless summer days, we’d have contests to see who could throw the crab further into the sea, our own version of playing horseshoes. Torture of animals is a sign of certain psychopathologies in children, and if it had been kittens we tossed into the sea by their tail, my parents would have certainly intervened—but the horseshoe crab raised not an eyebrow. My re-introduction to the crab, many years later, makes me shudder at my callous girlhood antics. When I began this research project in 2013, perhaps it was some sort of psychic penance for the sins of my former self.

Beyond a sentimental attachment to crabs, much later in life I become aware of horseshoe crabs’ vast contributions to human life through their sacrifice for biomedicine, fishing, and evolutionary theories. As I have written this book, horseshoe crabs have transformed my awareness of the world. They are both materially wondrous as well as symbolically generous. Observing the crabs, their habits, movements, growth, I’ve come to appreciate the shoreline in a new way. Like honeybees, horseshoe crabs are designated an indicator species, a biological species that provides useful data to scientists monitoring the health of the environment. Through associations and extrapolations, scientists are able to track the migration, health, and fertility of other species and can infer the sustainability of habitats. Indicator species, also known as sentinel species, are useful for biomonitoring ecological health, and horseshoe crabs can serve as a proxy for the health of shorelines. If the horseshoe crabs leave, migrate, or die, that indicates that the environment is degraded. I, too, have come to see the horseshoe crab as signifying larger ecological and sociological trends—rising seas, biological interdependence, geologic time.

My study centers on interviews with over 30 conservationists, field biologists, ecologists, and paleontologists and over 4 years of fieldwork (2012–2016) at urban beaches in the New York City area; natural preserves in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan; and marine research sites in Cedar Key, Florida.1 In Catch and Release, I explore the interspecies relationships between humans and horseshoe crabs—our multiple sites of entanglement and enmeshment as we both come to matter. As I show, crabs and humans are meaningful to one another in particular ways. Humans have literally harvested the life out of horseshoe crabs for multiple purposes; we interpret them for understanding geologic time, we bleed them for biomedical applications, we collect them for agricultural fertilizer, we eat them as delicacies, we capture them as bait. Once cognizant of the consequences of harvesting, we rescue them for conservation, and we categorize them as endangered. In contrast, the crabs make humans matter by revealing our species vulnerability to endotoxins,2 a process that offers career opportunities and profiteering from crab bodies, and fertilizing the soil of agricultural harvest for human food. In these acts of harvesting, horseshoe crabs and humans can apprehend important ecological events: geological time shifts, global warming, and biomedical innovation. My work situates the crabs within my own intellectual grounding in sociology; however, this sociological perspective is not seamless, it is rife with debate.

A major contribution of sociologists to contemporary thought is our production of theories and methods to determine, measure, and interpret social stratification and human inequity. Any introductory sociology course worth its weight provides students with critical thinking tools to examine race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability as social constructs that constrain our lived experiences. Armed with sociological insights to understand racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism, ageism, and ableism, the student explores how personal feelings are entangled with structural location. As a sociologist, I’ve made my living analyzing, teaching, and investigating aspects of human inequity, but I’ve recently come to consider the ways we determine the relative status, rights, or power of nonhuman animals. For instance, how do we explain how our companion animals—any cohabiting dog, cat, fish, or hamster—rank more highly than those pesky pigeons, rats, or roaches? What are the mechanisms we use to justify the relative worth of animals “scientifically proven” to be “closer” to us—such as gorillas, chimps, and other primates—versus those deemed more strange and distant—such as crickets, rattlesnakes, or frogs? The domination of humans over all other beings has created an assumption that our species has more value and, thus, has the right to act upon other species in our own interest. Speciesism, the belief in the inherent superiority of one species over others, was coined by the British psychologist Richard Ryder in Victims of Science: The Use of Animals in Research and popularized by the Australian philosopher Peter Singer.3

Speciesism is not just a ranking system of humans over all animals. Rather, humans create an even more specialized way of determining the worthiness of an animal—worthy of our care, our protection, our attention, and our love. How much we care seems to be very closely associated with how we regulate our scientific research and handling of animals. During an all-day visit to several shoreline field sites in Connecticut, the conservation ecologist Jennifer Mattei and I engaged in a philosophical discussion about the relative compassion for shorebirds compared to horseshoe crabs. I asked why so many seem to rank birds above the horseshoe crab. “It’s because it doesn’t have a backbone,” she instantly replied. I laughed, thinking she was joking and that the answer had to be more complicated than that. Although she was driving, she turned to make eye contact, and said, “I could crush a horseshoe crab, and no one would care, but if I did it to a bird, I would be arrested. Any research with animals with a backbone has all these protections. It’s total human bias that things more like us [require] more protection than things not like us.” I nodded, coming to terms with the fact that maybe it was as simple as that. She continued, “Who cares about a spider when they don’t have as many neurons as us and can’t feel what we feel? It’s the whole vertebrate-invertebrate divide.”4 Jennifer is right in the fact that the lack of a spine has had serious implications for the social status of the horseshoe crab and other invertebrates. Insisting that a backbone is required to feel pain creates a definitional absolute that leaves horseshoe crabs and other animals in an impossible position. Their responses to injurious stimuli are interpreted as something other than affect—a reflex—and as such, compassionate care does not need to be rendered. Despite mounting evidence,5 this popular and intransigent belief among many humans that animals without backbones do not feel pain influences our dismissive treatment of 95% of the total number of species on earth.6 But returning to horseshoe crabs specifically, what are the other distinguishing characteristics of this species?

Horseshoe Crab Biology and Anatomy

The ocean-dwelling horseshoe crab of North America, Limulus polyphemus, is a strange-looking animal. It crawls along the ocean floor with its maroon helmet-like hard-shelled top, the carapace, made of chitin and proteins. It has 10 “eyes” and six pairs of legs and claws underneath. In addition to its two compound lateral eyes, its other eyes are light-sensing organs located on different parts of its body—the top of the shell, the tail, and near the mouth. These eyes assist the crab in adjusting to visible and ultraviolet light and enhance adaptation to darkness in various environments, aquatic and terrestrial.7 A crab uses a nonpoisonous 4–5 inch hard tail, called a telson, to steer or right itself when it is overturned.8 The telson is dragged in the sand as the horseshoe crab lumbers along the shoreline. Adult crabs weigh 3–5 pounds and are 18–19 inches in length from head to tail for females (males are a few inches shorter). They can live for about 20 years. During spawning, they are either on the beach around high tide or swimming in 2–3 feet of water. When not spawning, they crawl along the bottom of the ocean at depths of 20–400 feet.9 On the shore, they are “slow and easy to catch” making them an ideal species for field biologists to study and to engage students.

Despite their spiny and spiky exterior, they are also comical to human eyes. As described by the biologist Rebecca Anderson, the first time she worked with horseshoe crabs she “pretty much fell in love with them because they look like these fearsome creatures with armored bodies and all their legs, but they are ineffectual as defenders. And they look so adorable when they walk on land.” It is difficult for most humans to observe horseshoe crabs in the water, but they have been described as “rather graceful compared to their tank-like appearance when they come to the shore.”10 Omnivorous creatures, they eat mostly clams and worms. They do so by crushing and grinding their food with their legs—or, more accurately, their knees—and shoveling the food into their stomach.

Anatomical illustration of the horseshoe crab. Illustration by C. Ray Borck.

Globally, there are four species of horseshoe crabs living on the continental shelf—one in North America, Limulus polyphemus, and three in Southeast and East Asia. The three species of horseshoe crab in Asia are Tachypleus gigas, Tachypleus tridentatus, and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda.

Some humans have been drawn to the horseshoe crab because it unlocks secrets about the “sea of life.” With a fossil record to verify its ancient lineage, the horseshoe crab is among the oldest old. According to geologist Blazej Blazejowski, when traced by looking at modification by descent, crabs haven’t changed morphologically over tens of millions of years and as such are stabilomorphs, organisms that are morphologically stable through time and space. Their closest relatives are trilobites, which lived from 510 millions years ago. Amazingly, the horseshoe crab has survived longer than 99% of all animals that have ever lived.11 One of the reasons the species have survived for so long is because of the composition of horseshoe crab blood cells called amoebocytes. The blood is copper based, and when it hits the air it turns blue. Because of the chemicals in the ameoboyctes, the horseshoe crab’s blue blood coagulates when it detects contamination. This instantaneous reaction to threat through clotting protects the animal from harm. It is this very quality of their blood, the ability to transform into a biopharmaceutical gel, that has been used to insure the safety of all injectables and insertables in human and veterinary applications.12

These ancient species are also remarkable because they are primarily aquatic, coming onto the shore for spawning and nesting for brief periods every year. Indeed, if we accept the anthropologist Stefan Helmreich’s definition—“the alien inhabits perceptions of the sea as a...