![]()

[ one ]

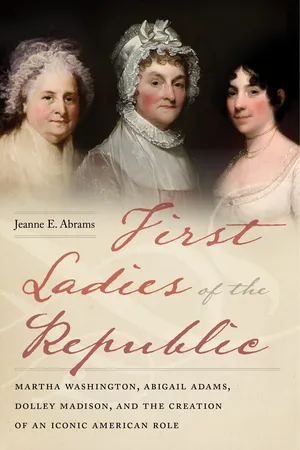

Martha Washington

The Road to the First Ladyship

I think our country affords every thing that can give pleasure or satisfaction to a rational mind.

MARTHA WASHINGTON to Janet Livingston Montgomery, January 29, 1791

When Martha Dandridge was born in Virginia in 1731, no one could have imagined that in little more than half a century, she would become known as Lady Washington, the wife of the first president of the United States and a central figure in the momentous events that occurred in Revolutionary America and the new republic. At the time of Martha’s birth, Virginia was a loyal American colony in the far-flung British Empire. British monarchs of royal blood ascended to the throne through the long historical tradition of inherited Divine Right, and commoners, even wealthy ones, would no more have aspired to head countries than to have contemplated flying to the moon.

The government of the new United States was created on a virtually blank slate, and in many respects, its birth and development served as a grand experiment. As the fledgling nation’s original First Lady, Martha Washington would have to craft the new role—albeit with strong direction (sometimes unwelcome) from the president and other members of his administration—and she certainly understood that her activities would serve as a precedent for her successors to follow. Martha may have undertaken her position reluctantly, but she proceeded thoughtfully and mindfully, carefully weighing her actions. Although her contemporaries recognized the critical role she played in her famous husband’s success and she commanded great respect during her lifetime, today the stereotypical portrait of Martha often portrays her as a charming but reticent woman. In many accounts of their lives, Martha emerges primarily as a faithful wife who stood loyally but somewhat meekly by George Washington’s side, attending to his personal needs and supervising mundane social events during the period he was viewed as the most famous and revered American of his era.

Yet on many levels Martha was central to Washington’s military and political success. Born into a modestly prosperous planter family, Martha was raised from a young age to be an efficient and capable household manager, a responsible member of the larger community, a welcoming and congenial hostess who knew how to make guests feel comfortable, as well as a dutiful wife and mother. In other words, Martha’s early training and life experience provided her with the skills to later succeed as America’s initial First Lady. Moreover, on an even more practical level, the wealth she inherited through her first husband allowed George Washington to realize many of his ambitious economic, social, and even political goals.

Raised in an earlier generation and a southern cultural milieu characterized by more rigid gender spheres, Martha Washington’s political vistas perhaps offered fewer avenues than those that opened up for her two successors, Abigail Adams and Dolley Madison. The dictates of eighteenth-century southern society held that a properly raised woman from the upper-class echelons should not exhibit a highly visible public role. And during her era, wifehood and motherhood were unquestionably considered the primary purpose of a woman’s life. But in reality, as Martha’s more recent biographers have suggested, she exercised more influence than has generally been acknowledged, ably helping to burnish George’s public image and build support first among his army troops during the American Revolution and later with his political colleagues and the larger American community. It is highly improbable that Martha was demonstrating a conscious feminist sensibility, for that would be inaccurately reading the past into the present, but she likely would have considered her support reflective of being a good republican wife, one who was conscientiously carrying out her duty to her spouse and the nation as part of the Washington family unit.

In the early republic, the social and political realms intersected on a daily basis, and political capital was built on relationships that were cemented during dinners, balls, and receptions, such as the Washington’s popular levees. Martha acquired new ceremonial duties, and in large gatherings held in the presidential mansion, she often entertained a mixed company of women as well as men, a tradition that would be continued by her successors. Martha may have privately disdained the public limelight, but that did not prevent her from presiding over, and helping to shape, the character of a variety of social events that enhanced George’s public reputation and brought other critical American political players into the new president’s orbit. In other words, she was not a neutral bystander during a period when the position of chief executive of the United States was still being tested and solidified, and by her demeanor and actions, she helped set the tone of Washington’s administration.

Indeed, in reality it was Martha Washington who launched the first event for the Republican Court, as it came to be known—the popular drawing room, which served a political as well as social purpose. It was supervised and guided by Martha and other elite women who lived alongside power and were drawn into the political sphere through their husbands, fathers, and brothers. For these early female members of America’s governing elite, it was often a joint cooperative undertaking, an effort in which they participated actively as part of the family unit. That central social occasion, the drawing room, and the attendant levees and dinners played a critical role in defining a “style of manners” for the new federal government, which helped distinguish it from the Old World regimen that characterized royal courts in Europe. It often meant fostering an atmosphere that sought to highlight the desired characteristics of “republican equality,” yet one that conveyed import and dignity at the same time.1

The concept of manners at the time extended far beyond mere social etiquette, for it placed special emphasis on upright personal character, virtue, and morality, seen as the bedrock of the infant republic.2 For Enlightenment-inspired American leaders such as Washington and his new vice president, John Adams, those values ideally led to behavior directed toward the public good of the new nation. Both men realized that women like their wives could help shape and guide private behavior at social events that had broader public implications, including bringing politicians from diverse regions of the country into a closer national configuration. Although Washington could often be stiff and somewhat unapproachable, throughout her lifetime Martha was uniformly praised for her sociability, ready smile, and talent for skillfully and engagingly conversing with people from all walks of life, an approach to social interaction she had internalized from youth. Her mellowing presence brought a degree of much needed civility to administrative occasions, often populated by bickering male politicians who espoused different visions for the construction of the new nation.

Born on June 2, 1731, Martha, affectionately nicknamed Patsy, was the eldest of eight children born to John and Frances Dandridge. She received a typical upbringing and a somewhat superior education for women of her era and class. The modest-sized but successful five-hundred-acre Dandridge family tobacco plantation of Chestnut Grove was worked by a relatively small number of about twenty slaves and located in agricultural New Kent County, Virginia. Martha was taught (probably under the primary tutelage of her mother) dancing, horseback riding, sparkling conversation, and other social graces as well as the skills needed for running a competent eighteenth-century household that would have included cooking, baking, sewing, candle making, and growing vegetables and herbs that could be used as food or transformed into medicinal remedies. Certainly, from a young age, she learned to be a good domestic manager and socially adept gentlewoman, a skill set that stood her in good stead when she became the wife of the well-to-do plantation owner Daniel Custis and later, after her second marriage to George Washington, as mistress of their large Mount Vernon home.

In addition, Martha learned to read and acquired basic math and writing skills, which enabled her not only to enjoy novels, poetry, and history books but also to capably manage household accounts. The latter was particularly valuable after the death of her first husband and before her remarriage to Washington. Religion was central to the lives of most early Americans, and the Dandridges were known as regular churchgoers and faithful members of the Church of England. Martha, who was a lifelong devout Episcopalian, personally held deeply ingrained religious beliefs that sustained her during periods of grief and heightened her sense of duty to family and community.

Not only did literacy allow Martha to pray daily and read her Book of Common Prayer and Bible3—to which she was reputed to have devoted an hour daily after breakfast—but it also allowed her later, as the wife of Washington, one of America’s most celebrated Revolutionary Patriots and noted military commanders and ultimately first president of the United States, to avidly follow newspaper descriptions of political events. After Washington retired from the presidency, Martha—and George—even subscribed to several books of essays published in 1798 by the American writer and women’s rights supporter Judith Sargent Murray, in which Murray argued that women possessed robust intellectual capacities, and therefore, like men, they, too, benefited from a strong education. John Adams, then the president of the United States, also purchased these volumes, so Abigail Adams, Martha’s successor as First Lady, was also exposed to Murray’s progressive views on female education.4

When Martha married the wealthy Daniel Custis, she moved up in social and economic status and became part of the colonial landed gentry and chatelaine of the Custis’s very comfortable and elegant home called White House, located on their Virginia estate in New Kent County. As a young woman, she enjoyed beautiful clothing and furnishings but tended to favor elegant simplicity over gaudy excess throughout her lifetime. Daniel, one of the wealthiest men in Virginia in his day, owned a number of tobacco planation farms in several counties as well as over two hundred slaves and a stately mansion in nearby Williamsburg, the capital and largest town in Virginia at the time. The local gentry enjoyed balls, plays, musical entertainments, and shopping in Williamsburg, and Daniel and Martha regularly visited the town, which was located about twenty-five miles from their main residence. In addition to running the busy household, supervising the work of the indoor enslaved men and women who acted as house servants, and bringing up their four children, Martha moved easily in Virginia social circles at parties and Sunday services and at other gatherings at St. Peter’s Church, where her husband was a vestryman. Even as a young wife and mother, her cheerful, lively, and caring personality was evident.5

But wealth and power were not enough to protect Martha from the death of two of her young children and her husband from one of the many illnesses that ravaged Americans in the eighteenth century. Although the cause is uncertain, Daniel Custis appears to have died from complications from a severe throat infection, coincidentally similar to the illness that later led to George Washington’s demise. Without the hallmarks of modern medicine, including antibiotics, reliable antiseptics, and anesthesia, a myriad of unidentified viruses and bacterial diseases claimed the lives of the rich as well as the poor with tragic regularity during their era.6

Daniel Custis died on July 8, 1757, at the age of forty-five intestate, that is, without having made a will. Fortunately for Martha, that meant in practice that she still received as a dower portion at least a third of his wealth (the rest being held in trust for her two surviving children), which included substantial property that totaled about 17,500 acres of land, but she was dependent on lawyers to execute the legal papers entitling her to take possession of the estate. Within days of her widowhood Martha, despite her grief and the needs of her young son, Jacky, and toddler, Patsy, was forced to turn to practical matters on the planation. In August, she was also already working on business related to Daniel’s tobacco exporting business and other financial concerns. She ordered mourning clothes and an expensive tombstone for her late husband and began a brisk correspondence with his London agents.

Widowhood significantly enlarged Martha’s economic power and personal independence as a feme sole. Soon Martha, with the initial assistance of her twenty-year-old brother Bartholomew (Bat), who was a lawyer, competently hired attorneys, business managers, and overseers to secure her legal rights and help carry out the work on the plantation farms and transactions related to selling their products. In a letter dated August 20, she firmly informed Custis’s London factor, Robert Cary, that her late husband’s “Affairs fall under my management . . . and I now have admon of his Estate. . . . I shall yearly ship a considerable part of the Tobacco I make to you which I shall take care to have made as good as possible and hope you will do your endeavor to get me a good Price.”7

Given the social norm at the time that most elite southern women were expected to have little active interaction in the overtly public world of commerce, it is noteworthy that Martha almost immediately embarked on a surprisingly effective business campaign. She first acquired power of attorney for the estate, collected on outstanding debts, made personal loans, and penned her own letters to her creditors and bankers.8 Many years later, presumably based on her own experience, she would advise a widowed niece to “exert yourself in the management of your estate. . . . A dependance is, I think, a wretched state and you have enough [funds] if you will manage it right.”9

Before long, Martha turned to the question of remarriage. Colonel George Washington, who had made a name for himself during the French and Indian War, emerged among her suitors as a promising choice as a potential spouse. They shared many interests, with both George and Martha enjoying plays and music, and George especially was also a devoted and energetic dancer. At around six feet three inches tall, the imposing muscular military man towered over the petite, attractive Martha, who at only five feet tall was already inclined to plumpness. They may have met previously at a Virginia social function, but they appear to have been reintroduced at the home of a mutual friend in March 1758, and they were married the following year. Whether Martha “fell passionately in love with George almost immediately,”10 as one of her biographers has claimed, is questionable, but she certainly developed a deeply heartfelt and abiding love and respect for him over the long years of their marriage, as he did for her. But in their day, marriage was often viewed as a strategic alliance. Men and women were expected to marry within their social set, and the Washington marriage brought advantages to both parties.

Although the two initially disagreed about which of their two plantation estate houses, White House or Mount Vernon, should become their home, Washington prevailed. George and Martha were married on January, 6, 1759. Within a few months, the newlywed couple, now a readymade family with the inclusion of Martha’s two remaining children, moved into George’s estate house, at that time a more modest edifice than the Custis family home. After their marriage, Martha reacquired the designation of a feme covert, once again coming under the full dominion of a beloved and indulgent husband, but one who had full legal control over virtually all aspects over her life, including her land, slaves, finances, and even her children. Yet Martha appeared to be content with the arrangement, as did George, who informed a friend he was happily retired from the military world to Mount Vernon “with an agreeable consort for life.”11

Mount Vernon was composed of five plantations, and with his newfound wealth, George purchased additional land and slaves to raise more tobacco. From the start of their marriage, the Washingtons set out to make their home one of the finest of its kind in Virginia, filling it with handsome furniture, beautiful paintings, ornate china and silver, and other exquisite household accoutrements. Many items were imported from England, as both the Washingtons considered themselves loyal British subject...