![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Human Rights, Development, and Debt

QUESTION 1

What is meant by “developing countries” (DCs)?

First we need to define the vocabulary. The terms North, rich countries, industrialized countries, or Triad all refer to the countries of Western Europe, North America, Japan, South Korea,1 Australia, New Zealand, and a number of other high-income countries (see list in Appendix).

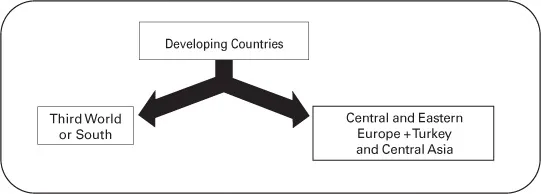

However debatable it may seem to group such diverse countries as Thailand, Haiti, Brazil, Niger, Russia, or Bangladesh in one category, we have chosen to adopt the terminology found in the statistics provided by the World Bank and the IMF, as well as the OECD, the UNDP and other UN agencies. Thus we refer to all the countries outside the Triad as developing countries (DCs). In 2008 there were 145 of these according to our figures. Within this category we make the distinction, for historical reasons, between the group of countries designated as Central and Eastern Europe, Turkey, and Central Asia, and the others—Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific—classified as the Third World or South (see list in Appendix).

In 1951, I spoke in a Brazilian journal of three worlds, although I did not actually use the term “Third World.” I invented and used that expression for the first time when writing in the French weekly l’Observateur, on 14 August 1952. The article ended: “Because finally this Third World—ignored, exploited and despised as was the Third Estate— also wants to be something.” I thus transposed Sieyes’ famous words about the Third Estate during the French Revolution.

—ALFRED SAUVY, French economist and demographer

Distribution of developing countries is as follows:

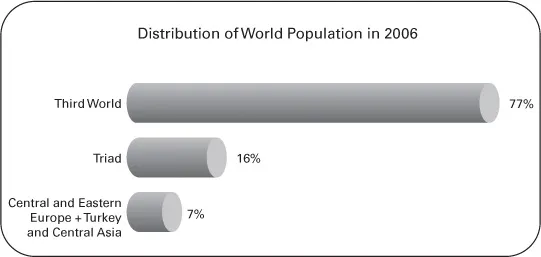

Out of a world population of approximately 6.5 billion people, about 84 percent live in the developing countries:

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 20082

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the conventionally accepted indicator used by many economists to evaluate the production of output (goods and services; see Glossary) in the world. However, the information it gives is incomplete, biased, and questionable, for at least four reasons:

1. It does not take into account unpaid work, provided mainly by women;

2. Damage to the environment is not treated as a debit;

3. The unit on which the calculation is based is the price of a commodity or a service, and not the amount of work it requires;

4. Inequalities within a country do not enter into the calculation.

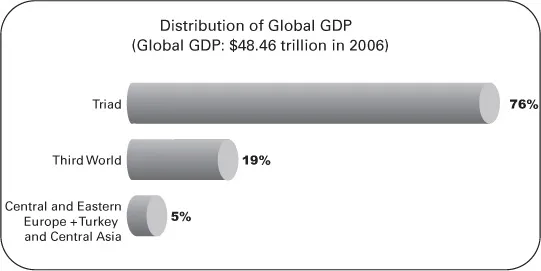

Despite these inadequacies, GDP is an indicator of economic imbalances between North and South. GDP and all other monetary figures appearing in this book are expressed in U.S. dollars, since 60 percent of exchange reserves, international loans, and exchanges are still transacted in this currency.

The production of wealth is largely concentrated in the North, and is almost inversely proportionate to the distribution of population:

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2008

Neoliberal globalization has been actively promoted by the authorities of the rich countries, which receive most of the profits, even though this can only be to the detriment of billions of inhabitants in the developing countries, as well as a large number of those in industrialized countries.

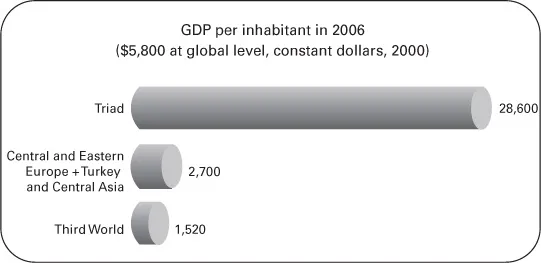

The GDP per inhabitant data reveal the economic gulf separating North and South (see below). However, this provides an incomplete overview of the world economic situation, as it ignores the often flagrant income disparities within a given category of country.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2006

The income of the world’s 500 richest people exceeds the cumulative income of the world’s 416 million poorest people.

—UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM3

Consequently, it is never useful to oppose North and South in overall terms. These words are used only to express a geographical state of affairs: most of the decisions are made in the North and have serious consequences for the developing countries. Nevertheless, within each region, the same mechanism of domination exists. In the final analysis—and this is fundamental—the main problem is the oppression of one part of humankind (not exclusively located in the South) by another part, much smaller in number but much more powerful. In other words, very different interests separate those who are subjected to the present system (the majority of the population in both North and South) from a relative handful of individuals who benefit from it, in both North and South. This handful of individuals makes up the capitalist class, which is driven by the desire for maximum profit. It is therefore crucial to make the right distinction, to avoid misunderstanding some of the underlying issues and failing to identify interesting alternatives.

You would help the poor, whereas I want poverty abolished.

—VICTOR HUGO, Ninety-Three

QUESTION 2

Why is the term “development” ambiguous?

The term developing countries implies that these countries are making progress and “catching up” with the highly industrialized countries—as if there were only one way to “develop,” as if the industrialized countries were the absolute development model, and as if some countries were further along the road than others in the race to make up for lost time. The purpose of using this pernicious term is to have the world believe there is only one possible form of development, and to legitimize the decisions of the major powers and institutions that share the same logic, while marginalizing the arguments of those who affirm that there are other possible, and even essential, alternatives.

The conventional idea of development is far from neutral: it has a strong ideological connotation and conceals choices that can legitimately be questioned. The term was used for the first time in 1948 by U.S. President Harry Truman:

We must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas. . . . Their poverty is a handicap and a threat to them and to more prosperous areas. . . . The material resources which we can afford to use for the assistance of other peoples are limited. But our imponderable resources in technical knowledge are constantly growing and are inexhaustible. . . . we should foster capital investment in areas needing development. Our aim should be to help the free peoples of the world, through their own efforts, to produce more food, more clothing, more materials for housing, and more mechanical power to lighten their burdens. . . . All countries, including our own, will greatly benefit from a constructive program for the better use of the world’s human and natural resources. Experience shows that our commerce with other countries expands as they progress industrially and economically. Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace.

—HARRY TRUMAN, State of the Union address, 1948

Aimé Césaire deconstructed this message clearly and concisely:

In other words, big American finance considers the time has come to grab all the world’s colonies.

—AIMÉ CÉSAIRE, Discourse on Colonialism, 1950

Moreover, one should note that this kind of development overlooks two essential aspects: the living conditions of populations and the ecological constraints imposed by the finite resources of our planet. Sixty years after Harry Truman’s speech, the words growth and sustainable development have replaced the term “development.” The economic press is full of analyses defending a development presented as healthy and worthy of every kind of sacrifice. The world’s financiers point to China and India as models—countries where companies are relocating, growth is strong, labor is dirt cheap, and working conditions deplorable. So what is behind such growth?

The economic growth of a country or region is directly related to the policies practiced there. Similar figures notwithstanding, the reality of the situation can vary widely from one case to another. Economic growth ought to reflect improved living conditions, in particular for the poorest, enabling them to take part in the country’s economic activity and thereby encouraging the development of local businesses that will produce goods and services primarily for the domestic market. This is not the case today. Growth today is an unfair process by which the global economy is in the hands of huge transnational corporations whose turnover often exceeds the gross domestic product of certain countries, or even whole continents. These corporations operate all over the planet but are careful to maintain powerful roots back home, where they generally rely on the state to protect their interests (ExxonMobil and Boeing are supported by Washington, Total by the French government). Along with the transnationals of the highly industrialized countries, we now see the emergence of powerful transnationals based in developing countries (Lenovo in China, Petronas in Malaysia, Petrobras in Brazil, Celtel in Africa, Techint in Argentina, Anglo-American in South Africa, Tata in India, and so forth). The capitalists and traditional political elite of the South profit comfortably from this situation, while the economies of their countries are forcibly tied to the global marketplace. In the prevailing model, their growth is largely reliant on exports. This means that commodity prices and outlets for their manufactured goods are essentially dictated by the most industrialized countries. An economic downturn in the United States, Europe, or Japan can have dramatic consequences for the economies of the developing countries because they depend so heavily on exports to these powers. To make matters worse, the export-driven growth model in no way seeks to satisfy basic human rights or emancipate peoples in the South. Indeed, the proponents of unfettered economic growth are careful to conceal its impoverishing potential. In reality, this growth model invariably leads to destruction of the environment, widening inequalities, and unlimited accumulation of wealth to the exclusive benefit of a tiny minority, while an overwhelming majority of the population lives in increasingly precarious conditions.

What development are we talking about? Are we talking about the neoliberal development model which means that 17 people die of hunger every minute? Is it sustainable or unsustainable? Neoliberalism is to blame for the disasters of our world. We do not put out the fire and we leave the arsonists in peace.

—HUGO CHÁVEZ, president of Venezuela, World Summit on Sustainable Development, in Le Monde, September 4, 2002

Unrestrained growth as advocated by the present system is not self-perpetuating. To last, it must continually create new consumer needs, pollute in order to purify (water, for example), and destroy in order to rebuild (see Iraq). The tsunami of December 2004 was “positive” for Asia’s growth (even if it caused the death of 200,000 people), because the industrial areas were not affected and rebuilding is proving long and costly. To sustain the pace of private automobile development, the agro-fuel sector (which we are tempted to call necro-fuel, since vast land areas are given over to its production instead of producing vital food) is booming, thus causing steep price hikes for certain food products and increased undernourishment in many developing countries.

If nothing is changing, as we stand at the threshold of an ecological crisis of historic gravity, it is because the powerful ones of this world don’t want it to. . . . The pursuit of material growth is for the oligarchs the only way of making societies accept extreme inequalities without questioning them. Growth creates a surplus of apparent wealth which oils the system without changing the structure.

—HERVÉ KEMPF, How the Rich Are Destroying the Earth, 2008

However, all peoples have the right to decide their own future and to possess the means to do so. This will not be possible as long as growth remains the absolute indicator of the world’s state of health.

Not simply to develop but to develop oneself.

—JOSEPH KI-ZERBO, A quand l’Afrique?, 2003

Although we are aware of all the inadequacies and semantic manipulations, we will be using the notion of developing countries throughout this work to allow us to refer to the statistics of the international institutions and place them under scrutiny. Thus the reader can check the data we ourselves provide with the data presented on these institutions’ websites and in their printed publications.

QUESTION 3

What is the link between debt and poverty?

The living conditions of the most deprived have deteriorated almost everywhere over the last twenty-five years, though at different times, to different degrees, and at different rates from one country to another. Several developing countries were hit very early in the 1980s (Latin America, Africa, and some countries of the former Soviet bloc), and others were struck only in the second half of the 1990s (Southeast Asia). International institutions have persisted in demanding repayment of the external debt. They make it a priority in their pursuit of dialogue with the governments of indebted countries. Yet we shall see that there have been many reasons why governments of the South could refuse what is often an immoral and illegitimate debt. Political, economic, social, moral, legal, ecological, and religious arguments have their place in this debate. But the pressures exerted by the great moneylenders of the world and the collusion between the ruling classes of North and South are such that most leaders of developing countries have no qualms about seeing their populations crushed by the burden of debt.

In government, you can only spend what you can earn. I inherited a very big debt that we are trying to reduce, while respecting a primary surplus of 4.25 percent, because it is important to show my creditors that I am responsible, that I pay my debts.

—LUIS INÁCIO LULA DA SILVA, president of Brazil, in Le Monde, May 25, 2006

The debt in the developing countrie...