![]() Part I

Part I

PILÓN![]()

1. DECEMBER 1955

A Tap on the Shoulder

IT IS A DAY IN PILÓN much like any other, except that it’s late in the year, so it’s cooler and there is more traffic in town. Here on the island’s Caribbean coast, it is the start of the zafra. Sugarcane, bright green in the fields, arrives from the surrounding plantations on wagons that roll along the streets leading to the sugar mill. This is a factory town, but more reminiscent of the Wild West, with noise and bustle and farmers traveling the unpaved streets on horseback.

Celia, as always, wakes up early. Her bedroom sits to the back of the house, overlooking the patio and part of her garden. A door from her room leads directly onto a wide verandah. At its end, on a corner post, a radio occupies a shelf. She turns on the morning news, broadcast from Havana. The house is clapboard, L-shaped, single-storied, with verandahs on three sides, and stands elevated about three feet above humid ground. It is simple enough, but—and everyone agrees—it is the prettiest house in town. The furniture, mostly antique, includes Cuban pieces shaped from palm trees, woven from willow branches, or of pine clad in cowhide. The rest is imported: rattan from the Philippines, with slipcovered cushions, or her parents’ wedding furniture, made in Italy, carved and upholstered, and purchased from her Spanish grandfather’s department store in Manzanillo.

The Cabo Cruz sugar mill in Pilón, Oriente Province, Cuba. (Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos)

Celia and her father live in one of the “yellow houses” inhabited mostly by mill management—called this not because they are painted that color but because they alone get a few hours’ electricity each day, and glow at night. Pilón is company-owned.

At the end of the year the southeast coast enjoys a breeze off the Caribbean and the air is fresh; it is the best time of year for growing flowers. Standing on the verandah, she can admire the gardens wrapping the house on three sides. As she walks along the side porch, she says a few affectionate words to the birds in cages hung at intervals along this outdoor living space: the glider, hanging swing, and rocking chairs are all empty at this early hour. What sets the house apart, besides Celia’s flair for decoration, are her father’s collections of books, artifacts, and nineteenth-century Chinese porcelain pieces, their colors predominantly vibrant shades of rouge, with black, green, and gold leaf accents.

She takes beauty seriously: her hands are carefully manicured; she always wears makeup, paints her lips bright red. She dresses well, copying clothing shown in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. She is extremely slender, but there is nothing flat about Celia. Errol Flynn later summed her up for the L.A. Examiner: “36-24-35.” The full-skirted dresses she favors, the look of the 1950s, show off her bust and narrow waist.

She pulls her thick black hair into a ponytail. Her look is pretty, but doesn’t stop there, surging over into another category suggesting, or revealing, maybe warning, that she is smart as well. Most telling is the way she shapes her eyebrows into thin, high arches with a line upward—like the accent marks over the final letters of José Martí.

In rope-soled alpargatos, with long multicolored ribbons tied securely around her ankles, she walks almost silently along the side porch to the front of the house where the porch gives onto the small front garden and the street. This section serves as the waiting room for patients. Coming in from surrounding plantations as well as the town, they await the doctor, who is still asleep. In this season, when the mill runs around the clock, patients begin to arrive at dawn or even wait through the night. Celia looks at the narrow strip of garden that separates the house from the street.

When I first visited Pilón in 1999, this little garden had dark red and bright green plants spelling CELIA on one side of the walk leading to the front door, FIDEL on the other.

CELIA’S LIFE FOLLOWS A CHARMING, even genteel pattern: each day she goes into the kitchen to greet Ernestina, the cook, and they talk about various things: food and children, since Ernestina was expecting a child, and any bits of information Ernestina might have gleaned from neighbors on her walk to work. It is a conversation they have carried on for fifteen years.

The house and medical office of Dr. Manuel Sánchez. He and Celia moved to this house, in Pilón, in 1940. (Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos)

Ernestina brews coffee, and Celia pours a cup and carries it to her father’s room, at the back of the house next to her own. In the bathroom with its smooth floor, walls, and ceiling finished in wood, she fills the porcelain tub, mixing the water carefully to temperature, and opens the window looking out on the inner garden. The window sill is so low that a person could leap straight from the tub onto the patio, paved in stone and shaded by a gigantic mango tree.

As the bath fills, Celia lays out towels, hangs a freshly laundered medical jacket on a hook on the wall, placing her father’s trousers, underwear, socks, and shoes nearby. Manuel Sánchez prefers lightweight Florsheims, American-made, but any attachment to the United States ends there, with those shoes.

In the kitchen, she’ll have cocoa and toast as she goes over the day’s menus. Celia has given Ernestina the menus for the week, loaded the pantry with provisions for the month—this is the tropics, even butter comes in a tin—and makes sure the vegetables and meat have been brought down from the family’s farm in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra. Even though Ernestina must know every recipe by heart, it is important that each dish be prepared the way Dr. Sánchez likes it. While he bathes, dresses, and has breakfast, Celia readies his three medical rooms. In the consultorio, she’ll file papers, straighten his desk, shelve books; in his surgery she’ll lay out instruments; and finally she will check the medical bag he’ll carry for afternoon house calls. She’ll keep an eye out for Cleever, the gardener, and, if the need arises, have him saddle horses and help load them into a launch, so she and her father can travel along the coast, disembark, and ride up into the mountains to make remote house calls. She also will make sure that their Ford has a full tank.

It is now 7:00 a.m. The office is about to open and Celia is ready to schedule. She will talk to all the patients waiting on the porch and learn why they have come. Not all visits to Dr. Sánchez are medical. Pilón, despite the greater area’s roughly 12,000 inhabitants, has no priest, and the nearest Catholic church with a priest in residence is in Niquero, about 25 miles away on roads marked on a 1945 map as seasonal with long impassable periods. Few people go to Niquero from Pilón unless they own a car—and few people do—and coastal ferries do not go there and return on the same day. So the doctor is consulted about family matters, abuse, disputes, confessions, ambitions; he sometimes acts as a marriage broker. Such consultations go hand in hand with diagnosis and treatment of malaria, water-borne diseases, tuberculosis, malnutrition, gunshot and knife wounds, and alcoholism, as well as the more natural adjuncts of a rural doctor, dentistry and delivering children. Everybody comes to Dr. Sánchez; he does not insist or even expect that all his patients pay.

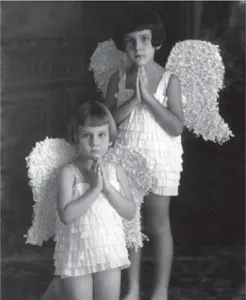

Celia (standing, left) was the middle child of eight children, preceded by Chela (Graciela), Silvia, the oldest, and Manuel Enrique. She was followed by Flávia (seated, front left), Orlando, in the middle, and Grisela. This studio photograph was taken in 1925 or 1926, before the birth of the baby Acacia and the death of Celia’s mother, Acacia Manduley. (Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos)

Celia has been following this daily pattern for fifteen years, and soon will begin the sixteenth. Or so things appear. She isn’t stuck here in Pilón; she likes it and has a small side business selling accessories, for which she travels fairly often to Miami. She is her father’s assistant; people call her “the doctor’s daughter.”

He delivered her on May 9, 1920, at 1:00 p.m. at home, in Media Luna, a town farther up the coast. He and his wife, Acacia, took her to the civil registry on October 16, 1920, and registered her as Celia Esther de los Desamparados Sánchez Manduley. Celia, after her grandfather Juan Sánchez y Barro’s first wife, Celia Ros; they chose her middle name from the liturgical calendar, Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados, our lady of abandoned ones. She was a middle child of eight children, preceded by Silvia, Chela, and Manuel Enrique, and followed by Flávia, Griselda, Orlando, and the baby Acacia, named after their mother. Celia’s mother died when she was six, and Celia had needed special attention following this separation because she had suffered mild anxiety neurosis, begun to cry frequently, developed a fever. Her father had kept her out of school, although she was nearly seven, to enter later with Flávia, who was a year and nine months younger. He taught her himself, and continued to do this even after she entered school, and hired special tutors for her.

Celia will work with her father until ten, or until he leaves the house for his small clinic in the sugar mill; then she is free to supervise the house or work on one of her many projects. She is an avid gardener, likes any activity that takes place outdoors, and she has a personality that is more cowgirl than housewife in this regard. Deep-sea fishing is her favorite sport, picnics her favorite pastime, and flowers—especially orchids—are her passion. Her main collaborator and sidekick, Cleever, is Jamaican, and lives with his wife at the edge of the garden. He keeps the shrubbery under control and implements her landscaping projects. The most recent are beds planted in patches of single colors to form designs. To make pocket money, she bakes and ices cupcakes, particularly during the harvest season, and Cleever takes them around town on a tray, knocking on back doors.

Celia and Flávia in a photographer’s studio in Manzanillo, c. 1926. (Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos)

ON THIS PARTICULAR DAY, she sits at the big worktable in the kitchen, reading the paper while she makes telephone calls: simultaneously talking, reading, planning, eating lunch, raising money for Epiphany, or Día de Reyes, on January 6, when members of her Catholic charity would be giving out toys to Pilón’s children. She had launched this activity in 1940, when she was twenty and new in town, setting a bit of a trend because the Catholic Church had never been active there, and not all that many of the area’s residents were Catholics. Pentecostalists and Spiritualists thrived in Pilón and in the surrounding hills.

As 1956 approaches, it is again time to sell raffle tickets and prepare for the church supper on New Year’s Eve. She’ll go, before that, to Santiago and buy toys in bulk. This year, because the sugar workers have been on strike, there is little money around. Calling merchants, Celia reminds them to donate items for the raffle, or make pledges of food, pointing out that parents with little or no work are counting on these gifts.

Sometime on this day, she gets a message. If it comes by telephone, it is almost certainly coded. More likely it is spoken, by one of those who wait on the porch, who otherwise appear as patients to see the doctor. Fidel Castro sends word that his right-hand man, Pedro Miret, is coming to Pilón. He will be accompanied by the 26th of July Movement’s national director of action, Frank País. Castro wants her to show them locations along the coast where he and his guerrilla fighters, returning from exile in Mexico, can land.

However it reaches her, the message is a tap on her shoulder, an invitation to become one of the instigators of the revolution that Castro had put in motion last July. Clearly Celia is not solely what she appears to be: a father’s daughter, a civic-minded and house-proud woman, a member in good standing of the provincial gentry. Although, she is those things as well. It might be tempting to say she is unique in her place and time.

She was, in fact, fairly representative: a thirty-five-year-old woman in 1950s Cuba, looking for a person (it could have been nearly anyone), or political party, or any movement whose objective was to remove Fulgencio Batista from power.

Since Batista seized the presidency by a coup d’état in 1952, Fidel Castro had emerged in the minds of many as the person most likely to end the dictator’s reign. He fearlessly, even rashly, had led an attack against the Moncada garrison, the national army’s command headquarters in Santiago. The army reacted with extreme force, summarily executing most of the participants, but Fidel escaped the massacre, aided, in part, by the Archbishop of Santiago, Monseigneur Enrique Pérez Serrantes, Spanish, sent to Cuba in 1922, who had personally tried to protect the few survivors of the 26th of July attack. The Archbishop even went so far as to search for the young revolutionaries hiding in the hills, dressed in his cassock, carrying a cross, and (some say) using a megaphone. Fidel argued his own defense at trial, was imprisoned for a time, and released in May 1955. Less than two months later, he went into exile. Between his release from jail and his exile in Mexico City, he founded his revolutionary 26th of July Movement, named for the day in 1953 when the Moncada was attacked, and took on one goal: removing Batista. Celia had decided to join Fidel and his movement.

After the 1952 coup, she, along with everyone suspected of opposing the dictatorship, was put on the list of organizations considered dangerous. This wide range included her fellow members of the Orthodox Party, formed legitimately in the late 1940s and led by the popular Eduardo Chibás. Not intimidated by being listed, she became an activist. She joined two clandestine anti-Batista groups, headed by men in the coastal towns of Campechuela and Manzanillo.

Even before the attack on the Moncada or the formation of these groups, she and her father had carried out a personal project that had its own seditious element. On May 21, 1953, along with a small group of Martí scholars, they erected a statue of Martí on the top of Cuba’s highest mountain, Turquino Peak in the Sierra Maestra. This range extends along the southern coast. They approached from a small wharf on the Caribbean, from the southern side, where the land dips below sea level then soars to an elevation of 6,560 feet. The military had been intent on the packing case the group hauled up, imagining it held guns, so had kept up surveillance as it was transported to the mountain. But Manuel Sánchez’s resistance project was conceptual: to place José Martí on the highest plane so he could reign over Cuba. The feat’s oddity, as much as its symbolism, made an impression on military officials, who deemed all the participants suspicious. Later—during the Revolutionary War—Fidel would favor the lofty heights of Turquino’s western companion, a peak called Caracas, and make his command post there, just above the La Plata River.

Those who became activists in response to Batista’s seizure of power had already been struggling over more than a decade to reform Cuban politics. Ramón Grau had become president in 1944 through fraudulent elections. In 1947, a new political party was formed, officially named the Cuban People’s Party but generally called the Orthodox, and Manuel Sánchez established a branch in Pilón. The party leader, Eduardo Chibás, even stayed in the doctor’s house in 1948. He began his presidential campaign in Oriente Province, and there is a photograph of Celia wearing a hat, quite properly, sitting among the bigwigs on the platform. The new party showed its strength in the 1948 elections, increasing its power. Still, Carlos Prio Socarras, who succeeded Grau that year, was not appreciably better. It became obvious to Batista, who had ruled Cuba in the 1930s and was living in retirement in the United States, that even if he returned he would be unable to win the 1952 fall elections. It was that year he staged his coup. By the next year, police arrests and station house beatings were common. The police were out of control whenever and wherever they chose. Torture by police agents was so widespread, writes British historian Hugh Thomas, that Batista was compelled to give his “personal assurance” that it would be investigated.

The process by which Celia became a political person is not an unusual one. It is the story of how revolutionary and national liberation movements begin. It is precisely those without power—teachers, nurses, housewives, secretaries, telephone operators, cane workers, bus drivers—but with intelligence and self-esteem who quite legitimately make the decision to fight for their cause. The language of these movements addresses loss of freedom (this means free press, free speech, religious freedom, adequate incomes, adequate health care, access to a stable system of justice), and without access to those rights or freedoms, the participants come to the conclusion they have nothing to lose. So, they take chances. They organize. They become members of movements that are as passionate as they are imperfect.

HER VARIANT OF THAT STORY began in 1940, when Celia arrived in Pilón and embarked upon a rarely mentioned period of mourning. At fifteen, she had fallen in love with a young Spaniard, a Catalonian named Salvador Sadurní. He had arrived in Manzanillo after attending a U.S. business college, paid for by his uncle who planned to leave Sadurní his profitable hardware store in that city. Both Celia and her sister Flávia had left their father’s house after outgrowing the local school in Media Lunato to attend the Institute, a private school for girls, in Manzanillo. There Celia started a club she called Los Pavitos, whose members were mostly her sisters, cousins, and their friends. They went to their favorite park, walking in groups of three or four, and when they saw someone they wanted to get to know, they would invite him to a beach party or picnic, which they then organized with elaborate care.

Salvador Sadurní, from Barcelona, was older (nineteen to Celia’s fifteen), with a well-defined future. From friends, cousins, and a few photographs I’ve been able to piece together this relationship. Celia’s friend Berta Llópiz has no doubt he was “crazy, crazy for her,” and her Girona cousins added the telling detail that he and Celia, along with their friends, avidly followed the news of the Spanish Civil War, discussing whatever they’d read or heard on the radio. This was a cord that bound them all together, tightly; no matter where they were, these young friends—spunky, attractive, confident—would whip out a donation can that each carried along with school books, picnic baskets, and all their other paraphernalia, to collect money to support the Republican cause. I found out a bit more by probing Celia’s brother-in-law, Pedro Álvarez, husband of her sister Chela. He affirmed that Sadurní was a great guy, “one of the best,” but said that Salvador and Celia were each too independent to be a good couple. I pressed for a reason, and we agreed that Celia was still pretty young, only fifteen when she met Salvador, but they had stayed together and created an affectionate and devoted friendship. Pedro added that Sadurní spent his nights “singing to other women,” and at this point Chela broke into the conversation to remind her husband that Salvador had performed several pieces of music written and dedicated to Celia on a local radio station. Slowly, another image of the young man began to emerge: he had been a businessman-musician who spent his free time writing and performing songs. He played the guitar, would hire and rehearse musicians, then take them with him like troubadours, to serenade under people’s windows and perform the music he’d written. His group played at houses all over town. The families would send somebody down to the street with money and...