- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

We the People

About this book

A history of labour and the labour movement in the USA, originally published in the 1930s. Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. Hesperides Press are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork. Contents Include: Here They Come! - Beginnings - Are All Men Equal? - Molasses and Tea - "In Order To Form a More Perfect Union" - A Rifle, An Axe - A Strange, Colourful Frontier, The Last - The Manufacturing North - The Agricultural South - Landlords Fight Money Lords - Materials, Men, Machinery, Money - More Materials, Men, Machinery, Money - The Have-nots vs The Haves - From Rags To Riches - From Riches To Rags - The New Deal..Relief - . Recovery - .Reform - .Foreign Policy - "You Guys Gotta Organize" -

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I

Here They Come!

From its very beginnings America has been a magnet to the people of the earth. They have been drawn to its shores from anywhere and everywhere, from near and far, from hot places and cold places, from mountain and plain, from desert and fertile field. This magnet, three thousand miles wide and fifteen hundred miles long, has attracted every type and variety of human being alive. White people, black people, yellow people, brown people; Catholics, Protestants, Huguenots, Quakers, Baptists, Methodists, Unitarians, Jews; Spaniards, Englishmen, Germans, Frenchmen, Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Chinese, Japanese, Dutch, Bohemians, Italians, Austrians, Slavs, Poles, Rumanians, Russians—and the list is only just begun; farmers, miners, adventurers, soldiers, sailors, rich men, poor men, beggarmen, thieves, shoemakers, tailors, actors, musicians, ministers, engineers, writers, singers, ditchdiggers, manufacturers, butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers.

First came the Norsemen; then an Italian sailing in behalf of Spain; then another Italian sailing in behalf of England; then Spaniards, Portuguese, English, French; then an Englishman sailing for Holland. All of them discovered parts of America, explored a bit, then raised their country’s flag and claimed the land. They returned home and told stories (some of them true) of what they had seen. People listened—and believed and came. Millions came within three hundred years, sometimes at the rate of a million a year.

This unique immigration of peoples was not accomplished without difficulties and dangers. To cross the ocean in the Queen Mary or the Queen Elizabeth, steamships over nine hundred and seventy-five feet long weighing over eighty thousand tons, is one thing. But to cross the Atlantic in a sailboat perhaps ninety feet long and twenty-six feet wide, with a tonnage of only three hundred was quite another thing. (Ordinary ferryboats on the Hudson River average about seven hundred tons.) For over two hundred years the earlier immigrants poured into the United States in just such boats as these. Remember, too, that in those days there were no refrigerators—fish and meat had to be salted to be preserved, and very often the crossing took so long a time that all the food rotted.

Here is a portion of a letter written by Johannes Gohr and some friends, describing their trip from Rotterdam to America in February, 1732 (over one hundred years after the flood of immigrants began). “We were 24 weeks coming from Rotterdam to Martha’s Vineyard. There were at first more than 150 persons—more than 100 perished.

“To keep from starving, we had to eat rats and mice. We paid from 8 pence to 2 shillings for a mouse, 4 pence for a quart of water.”

Gottlieb Mittelberger was an organist who came to this country in 1750 in charge of an organ which was intended for Philadelphia. Here is a part of his story:

“Both in Rotterdam and Amsterdam the people are packed densely, like herrings, so to say, in the large sea vessels. …

When the ships have for the last time weighed their anchor at Cowes, the real misery begins, for from there the ships, unless they have good winds, must often sail 8, 9, 10 or 12 weeks before they reach Philadelphia. But with the best wind the voyage lasts 7 weeks …

That most of the people get sick is not surprising, because in addition to all other trials and hardships, warm food is served only 3 times a week, the rations being very poor and very small. These meals can hardly be eaten on account of being so unclean. The water which is served out on the ships is often very black, thick and full of worms, so that one cannot drink it without loathing, even with the greatest thirst. O surely, one would often give much money at sea for a piece of good bread, or a drink of good water if only it could be had. I myself experienced that sufficiently, I am sorry to say. Toward the end we were compelled to eat the ship’s biscuit which had been spoiled long ago; though in a whole biscuit there was scarcely a piece the size of a dollar, that had not been full of red worms and spiders’ nests. Great hunger and thirst force us to eat and drink everything, but many do so at the risk of their lives. …

When the ships have landed at Philadelphia after their long voyage no one is permitted to leave them except those who pay for their passage or can give good security; the others who cannot must remain on board the ships till they are purchased, and are released from the ships by the purchasers. The sick always fare the worst, for the healthy are naturally preferred and purchased first, and so the sick and wretched must often remain on board in front of the city for 2 and 3 weeks, and frequently die, whereas many a one if he could pay his debt and was permitted to leave the ship immediately, might recover. …

The sale of human beings in the market on board the ship is carried on thus: Everyday Englishmen, Dutchmen, and high German people come from the city of Philadelphia and other places, some from great distance, say 60, 90 and 120 miles away, and go on board the newly arrived ship that has brought and offers for sale passengers from Europe, and select among the healthy persons such as they deem suitable for their business, and bargain with them how long they will serve for their passage money, for which most of them are still in debt. When they have come to an agreement, it happens that adult persons bind themselves in writing to serve 3, 4, 5 or 6 years for the amount due by them varies according to their age and strength. But very young people, from 10 to 15 years must serve until they are 21 years old.

The last part of this letter is particularly valuable, because it introduces us to a system then very common. Many of the people who wanted to come to America didn’t have the money to pay for their passage. They therefore agreed to sell themselves as servants for a period of years to whoever would pay their debt to the captain of the ship. Frequently the newspapers carried advertisements telling about the arrival of such groups. In the American Weekly Mercury, published in Philadelphia, on November 7, 1728, there appeared the following advertisement:

Just arrived from London, in the ship Borden, William Harbert, Commander, a parcel of young likely men-servants, consisting of Husbandmen, Joyners, Shoemakers, Weavers, Smiths, Brickmakers, Bricklayers, Sawyers, Taylers, Stay-Makers, Butchers, Chairmakers and several other trades, and are to be sold very reasonable either for ready money, wheat Bread, or Flour, by Edward Hoane in Philadelphia.

And in the Pennsylvania Staatsbote for January 18, 1774, this item appeared:

GERMAN PEOPLE

There are still 50 or 60 German persons newly arrived from Germany. They can be found with the widow Kriderin at the sign of the Golden Swan. Among them are two schoolmasters, Mechanics, Farmers, also young children as well as boys and girls. They are desirous of serving for their passage money.

The contract which these unfortunates who were “desirous of serving for their passage money” had signed with the ship captain was called an indenture, and they were known as “indentured servants.”

Isn’t it amazing that in spite of shipwreck, rotten food, vermin, sickness, people continued to come by the thousands? Of course conditions did improve. By 1876 nearly all the immigrants came in large steamships which took only seven to twelve days to cross, instead of that number of weeks in a small sailing vessel, as heretofore. But even these furnished no pleasure cruise for steerage passengers. Edward A. Steiner tells the story of his voyage in the early 1900’s.

There is neither breathing space below nor deck room above, and the 900 steerage passengers crowded into the hold … are positively packed like cattle, making a walk on deck when the weather is good, absolutely impossible, while to breathe clean air below in rough weather, when the hatches are down, is an equal impossibility. The stenches become unbearable, and many of the emigrants have to be driven down; for they prefer the bitterness and danger of the storm to the pestilential air below. …

The food, which is miserable, is dealt out of huge kettles into the dinner pails provided by the steamship company. When it is distributed, the stronger push and crowd, so that meals are anything but orderly procedures. On the whole, the steerage of the modern ship ought to be condemned as unfit for the transportation of human beings.

And a woman investigator for the United States Immigration Commission reported in 1911:

During these twelve days in the steerage I lived in a disorder and in surroundings that offended every sense. Only the fresh breeze from the sea overcame the sickening odors. … There was no sight before which the eye did not prefer to close. Everything was dirty, sticky, and disagreeable to the touch. Every impression was offensive.

Now obviously no human beings would go through the hardships described above unless they had very good reasons. The end of the journey would have to promise a great deal to make it worth the sorrow of parting from relatives and friends, from all the fun, comfort, and security of home. It’s not easy to “pull up stakes,” and most people are apt to think a very long time before they do so. Then what made these millions and millions of people seek homes in a distant land?

Most of the immigrants came because they were hungry—hungry for more bread and for better bread. America offered that. Europe was old; America was young. European soil had been farmed for many years; American soil was practically untouched. In Europe the land was in the hands of a few people, the upper classes; in America the land was available to all. In Europe it was difficult to get work; in America it was easy to get work. In Europe there were too many laborers looking for the few available jobs, so wages were low; in America there weren’t enough laborers to fill the available jobs, so wages were high.

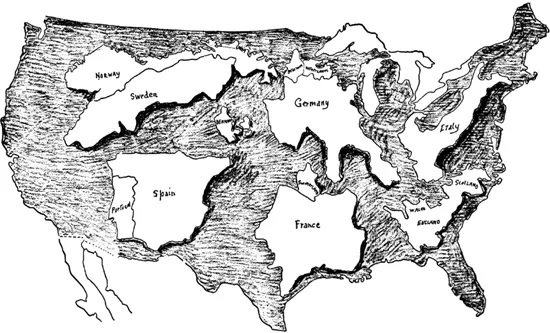

“In Europe there were large numbers of people without land; in America there were large areas of practically free land without people.” The map on page 8 will give you an idea of how vast, how huge this America was by comparison with European countries.

Not only was this land very extensive, but it was also very good. Here was some of the best farm land in the entire world; the climate and soil suitable for the production of practically every product of the temperate zone and for the grazing of millions of cattle; here were rivers thousands of miles long to water these fertile valleys; here were gold, silver, copper, coal, iron, oil—and all this bounty of nature was to be had for almost nothing. Off to America!

Here was a poor peasant living on someone else’s land, in a miserable hut with a leaky roof and no windows; or a person paying heavy taxes without having anything to say in governing his country; or perhaps someone who wanted to work but could not find anything to do, so that there was always too little to eat and no prospect of ever getting enough; if such people saw no hope of ever getting out of the hole they were in as long as they stayed where they were, naturally they would jump at the chance to move to a place described in this manner by a person who had seen it with his own eyes:

Provisions are cheap in Pennsylvania. The people live well, especially on all sorts of grain, which thrives very well because the soil is wild and fat. They have good cattle, fast horses, and many bees. The sheep, which are larger than the German ones, have generally two lambs a year. Hogs and poultry, especially turkeys, are raised by almost everybody. Every evening a tree is so full of chickens that the boughs bend beneath them. Even in the humblest and poorest houses in this country, there is no meal without meat, and no one eats the bread without the butter or cheese, although the bread is as good as with us. On account of the extensive stock raising meat is very cheap; one can buy the best beef for three kreuzers a pound.

MAP SHOWING COMPARISON WITH EUROPEAN COUNTRIES

Of course there did come a time when most of the free land in America had been taken up. But still the immigrants poured in. James Watt had perfected his steam engine, and many other inventions followed which changed the world’s way of making things. America was changing from a farm to a workshop. It happened that where formerly most of the immigrants had come from northeastern Europe—England, Ireland, Germany, Scandinavia—the new immigrants came primarily from southeastern Europe—Italy, Russia, Austria, Hungary, Poland. The new immigrants came not to take possession of and cultivate the land as in the past, but to work in the factories, the mills, and the mines. When trees were being felled, gold, copper, coal, and iron being mined, steel being made, clothing being made, railroads being built, workers were needed. And the more that came the greater was the need for more food, more houses, more bridges, more clothing, more autos, more trains, etc. As America changed from a farming country to a manufacturing and industrial country, labor moved from places where it was abundant and cheap, to America where it was scarce and dear. American manufacturers sent agents to all parts of the world to get men to work for them. America needed workers. Workers in Europe and other places needed jobs. Jobs were waiting in this new world. To America!

People came, then, and found land and jobs; at last they had enough to eat. Of course they described their good fortune in the letters they wrote to their relatives and friends at home. Everyone is interested in the adventures of those who leave home, and these letters were passed from hand to hand and eagerly read by all. A letter from America was an exciting event. Very often the people of a whole town would get together to hear some one read a letter from a friend in America. The truth alone was enough to make the stay-at-homes want to make the journey, and oftentimes some of the letters were highly colored, a little bit of truth and a great deal of imagination mixed together. An amusing story is told of an immigrant just landed, who saw a twenty-dollar gold piece on the ground, and, instead of bending for it, kicked it away with his foot.

Someone asked him: “Why did you do that? Don’t you know that is real gold?”

“Of course,” he replied, “but there are huge piles of gold in America to be had for the taking, so why should I bother with one piece!”

Very often the envelope that carried the letter contained also the passage money for those back home who were still hesitant or who had no money. Here was real proof of success to be made in America. On the one hand, letters describing the abundance of good things in America; on the other hand, food becoming more and more scarce. The result was immigration, despite dangers and difficulties. Off to America!

A bigger and better loaf of bread, then, attracted most of the inpouring hordes of people to America. But many came for other reasons. One was religious persecution. If you were a Catholic in a Protestant country, or a Protestant in a Catholic country, or a Protestant in another kind of Protestant country, or a Jew in almost any country, you were oftentimes made very uncomfortable. You might have difficulty in getting a job, or you might be jeered at, or have stones thrown at you, or you might even be murdered—just for having the wrong (that is, different) religion. You learned about America where your religion didn’t make so much difference, where you could be what you pleased, where there was room for Catholic, Protestant, Jew. To America, then!

Or perhaps you had the right religion but the wrong politics. Perhaps you thought a few people in your country had too much power, or that there should be no kings, or that the poor people paid too much taxes, or that the masses of people should have more to say about governing the country. Then, oftentimes, your government thought you were too radical and tried to get hold of you to put you into prison, where your ideas might not upset the people. You didn’t want to go to prison, so you had to leave the country to avoid being caught. Where to go under the circumstances? Some place where you could be a free man, where you weren’t clapped into jail for talking. Probably you turned to the place Joseph described in his letter to his brother. “Michael, this is a glorious country; you have liberty to do as you will. You can read what you wish, and write what you like, and talk as you have a mind to, and no one arrests you.” Off to America!

For several hundred years America was advertised just as Lucky Strike cigarettes and Buick cars are advertised today. The wonders of America were told in books, pamphlets, newspapers, pictures, posters—and always this advice was given, “Come to America.” But why should anyone be interested in whether or not Patrick McCarthy or Hans Knobloch moved from his European home to America? There were two groups interested at different times, but for the same reason—business profits.

In the very beginning, over three hundred years ago, trading companies were organized which got huge tracts of land in America for nothing or almost nothing. That land, however, was valueless until people lived on it, until crops were produced, or animals killed for their furs. Then the trading company would step in, buy things from the settlers and sell things to them—at a profit. The Dutch West India Company, the London Company, and several others were trading companies that gave away land in America with the idea of eventually making money on cargoes from the colonists. They wanted profits—needed immigrants to get them—advertised—and people came.

In later years, from 1870 on, other groups interested in business profits tried to get people to come to America. The Cunard line, the White Star line, the North German Lloyd, and several o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to Revised Edition

- Part I

- Part II

- Appendix: page references to sources of quotations

- Index

- Footnote

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access We the People by Leo Huberman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.