eBook - ePub

Five Hundred Years Rediscovered

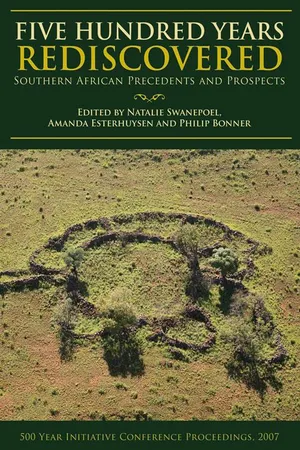

Southern African precedents and prospects

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Five Hundred Years Rediscovered

Southern African precedents and prospects

About this book

In the age of the African Renaissance, southern Africa has needed to reinterpret the past in fresh and more appropriate ways. The last 500 years represent a strikingly unexplored and misrepresented period which remains disfigured by colonial/apartheid assumptions, most notably in the way that African societies are depicted as fixed, passive, isolated, un-enterprising and unenlightened. This period is one the most formative in relation to southern Africa's past while remaining, in many ways, the least known. Key cultural contours of the sub-continent took shape, while in a jagged and uneven fashion some of the features of modern identities emerged. Enormous internal economic innovation and political experimentation was taking place at the same time as expanding European mercantile forces started to press upon southern African shores and its hinterlands. This suggests that interaction, flux and mixing were a strong feature of the period, rather than the homogeneity and fixity proposed in standard historical and archaeological writings. Five Hundred Years Rediscovered represents the first step, taken by a group of archaeologists and historians, to collectively reframe, revitalise and re-examine the last 500 years. By integrating research and developing trans-frontier research networks, the group hopes to challenge thinking about the region's expanding internal and colonial frontiers, and to broaden current perceptions about southern Africa's colonial past.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Five Hundred Years Rediscovered by Natalie Swanepoel,Amanda Esterhuysen,Phil Bonner,Joanna Behrens,Neil Parsons,Simon Hall,Mark Anderson,Jan Boeyens,Francois Coetzee,Shadreck Chirikure,Tim Maggs,Alan G. Morris,Edwin Hanisch,Peter Delius,M.H. Schoeman,Marilee Wood,John Wright,Ackson M. Kanduza, Natalie Swanepoel,Amanda Esterhuysen,Phil Bonner,Amanda Esterhuysen,Natalie Swanepoel, Natalie Swanepoel, Amanda Esterhuysen, Amanda Esterhuysen, Phil Bonner, Phil Bonner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Highlighting the period and the term 500 years may create in the minds of older scholars curious resonances and dissonances. Five Hundred Years was the title of a volume published by C.F.J. Muller of the University of South Africa in 1969. There it referred to the length of time claimed for white involvement in South Africa. The book had an entirely white frame of reference, and made next to no reference to an independent history of blacks (who mostly were brought under white domination 180-130 years before and whose past was relegated, in almost an afterthought, to an appendix) (Saunders 1988: 43). In 2006 a group of archaeologists and historians, young and old alike, centred mainly but not exclusively in the Gauteng region, became involved in what they called the Five Hundred Year Initiative. Their aim was to invert the old 500 years mindset and to make up for several decades of neglect of certain aspects of our historical and archaeological past. The most profitable route to achieving this goal they saw as interdisciplinary research which generated close collaborations between archaeologists, oral historians, social anthropologists, linguists and others. As their initial manifestos/grant proposals claimed, the last 500 years was a time of immense change, enterprise, and internal invention amongst African societies caught up in an internal African frontier which was subsequently, secondarily but nevertheless vitally impacted upon by a final ‘white frontier’. This involves at least partly a clearer awareness of what we have overcome, and upon which we can build, that is to say, the shortcomings, myopias, and the strengths of research and writing that has taken place mainly within the constricted confines of individual disciplines over the past decades. Since the principal academic domains which this preliminary volume straddles are archaeology and history, it is with a brief review of the pertinent past of each that this introduction begins.

History

South African precolonial history and archaeology have followed curiously similar paths. Until the 1940s most research on African societies in the precolonial and early contact period was conducted by amateurs, generally government servants involved in native affairs, or missionaries. George Theal, South Africa’s first historian to write extensively on precolonial African history and on African societies on the ‘other’ side of the frontier, worked initially as a teacher at the missionary educational institution of Lovedale and subsequently as a government official. James Stuart, who collected a huge body of oral data on the northern Nguni peoples and published several notable treatises on isiZulu, was an official of Natal’s Department of Native Affairs (Webb & Wright 1998; Hamilton 1998). A.T. Bryant, another notable scholar of precolonial Zululand and Natal, was also a missionary, as were Ellenberger, Wangemann, Merensky, Nachtigal, Ayliff, Boyce and others who collected voluminous data on African societies in the interior, some of which was published, though mostly not in English. Their central problem was a ‘settlerist’ bias, seen most clearly in the later published works of George Theal, which frequently depicted African societies as irrational, despotic and barbaric, but the data they collected, if viewed with a critical eye, remains an invaluable and irreplaceable source to both the precolonial historian and historical archaeologist alike. Indeed, as Saunders notes, Theal gave Africans more coverage than any other historian in a general work on South Africa before the first volume of the Oxford History appeared in 1969 (Saunders 1988: 21).

From the early 20th century little interest was evinced among white amateurs or academics alike in precolonial African history. The central theme in their researches and writings was the relations between and within South Africa’s white language groups, Afrikaners and English speakers. In this narrative, Africans were relegated to the background, something which the historian F.J. Potgieter described as ‘part of his (white settlers) environment, like the mountains, the grasslands and fever’ (cited in Bonner 1983: 70). Such a profoundly unenquiring attitude and such pervasive neglect was only punctuated occasionally by the writings of black converts and intellectuals, men like William Ngidi, Sibusiso Nyembezi, Mazizi Kunene, Samuel Mqhayi, William Gqoba, Magema Fuze, Sol Plaatje, Thomas Mofolo, John Soga and others who wrote between the 1880s and 1930s (for reviews see Saunders 1988; la Hausse 2000; Ndlovu 2001). While many of these voices have yet to be recovered – especially those that expressed themselves in the vernacular language and/or went unpublished – they remained few and far between.

The professional historian’s general lack of interest in African societies and a precolonial African past was then partly broken from somewhat unexpected quarters – the University of Pretoria journal Historiese Studies, which was published between 1939 and 1949. It remained mostly concerned about understanding what was happening on the black side of the black/white frontier in the interior. While racially skewed in its interpretations, it nevertheless excavated important documentary sources on subjects about which many modern South African historians still remain in ignorance. Where the Pretoria archaeologist J.F. (Hannes) Eloff stood in relation to this school might prove an interesting excursion in intellectual history. This brief awakening was however brought to an abrupt close (one assumes) by the establishment of apartheid.

The only other body of writers and scholars who took an interest in precolonial history were anthropologists, mostly working in the government service, and sometimes themselves the sons of missionaries, who collected historical data, selections of which were published in the important Department of Native Affairs (DNA) Ethnological series. These studies were distinguished and distorted by their own myopias and bias (S. Hall 2007: 165). Breutz, for example, believed stubbornly, despite the mass of rich oral evidence he collected to the contrary, that the huge ‘stonewalled’ settlements of the Tswana area belonged to a pre-Bantu-speaking population. Van Warmelo, the head of the ethnological section of the DNA, the unquestioned doyen of them all, whose contribution is still not adequately recognised, was intellectually and politically committed to recovering ‘tribes’ and frequently distorted his analysis to fit these needs. Their works necessarily had to fit into segregationist/apartheid schemas. Other professional anthropologists like the Kriges and Schapera also made unique and massive contributions to uncovering precolonial African history. Their weakness, all too often, however, was the prevailing structural functionalist paradigm that then dominated social anthropological studies, which tended to view African societies as relatively unchanging and removed politics and power from the analytical frame (substituting culture and custom in its place) (Fields 1985: 58). These scholars nonetheless assembled a massive and extraordinary archive on precolonial African history, most of it still unpublished and which remains to be adequately tapped.

Meanwhile mainstream historians remained resolutely uninterested in and disengaged from precolonial African history and developments on the African side of the frontier. On the one hand, Afrikaner nationalist historians focused on the emergence of the Afrikaner volk and its trials and tribulations at the hands of savage black tribes and of British imperialists. In this kind of history there was virtually no room for precolonial history, though in the 1960s and 1970s some Afrikaner nationalist historians sought to develop ethnically-based histories of black people to fit in with the homelands policy being implemented by the National Party government.

On the other hand, English-speaking popular historians tended to focus, as they had done for well over a century, on the advent of British settlers in the Eastern Cape in the 1820s and in Natal in the 1840s and on their subsequent transportation of ‘civilisation’ and ‘progress’ in the spheres of agriculture, mining and business across the subcontinent. Again, there was little room for precolonial history except by way of brief background to the white civilising mission; generally it was cast as having to do mainly with the migrations and wars of savage tribes.

In the Afrikaans-language universities, the great majority of historians were active propagators of Afrikaner nationalist history. In the English-language universities, most historians aligned to a greater or lesser extent with a fading colonial liberalism whose prime concern was with the history of ‘race relations’ in South Africa since the advent of white settlers in the mid-17th century.

An important shift in emphasis began to occur in English-language universities, mostly following on prior developments in universities in the United Kingdom and the USA, prompted in both instances by the decolonisation of Africa, in the 1960s. As decolonisation approached, a new generation of both black and white postgraduate students began to explore Africa’s precolonial past and to search for a useable history of the states which were about to be established. This shift was visible first in West and then in East Africa, and was paralleled by a similar engagement among African archaeologists with Iron Age archaeology. It spilled over into South African studies in the late 1960s. Thompson’s (1969) edited volume on African Societies in Southern Africa and the African Studies seminar at the School of Oriental and African Studies (where a generation of postgraduate students were inspired by Shula Marks) were landmark developments in this regard. Following on the heels of this process, English-language universities in South Africa began to mirror this trend and created the institutional and intellectual base for a slowly growing number of academic historians to begin researching, writing and teaching topics in the history of South Africa’s black societies, including precolonial history. Here the study of the history of black societies provided more progressive white students and academics with a means of intellectually challenging some of the main tenets of apartheid and of white domination more generally.

From the first, precolonial history attracted a cohort of able and energetic researchers. The main theme which they took up was the formation of African states in the late 18th and early 19th centuries – the Zulu, Swazi, Sotho, Pedi, Gaza, Ndebele and others – and their relations with one another and with the Cape, Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. Other researchers examined the histories of chiefdoms among the Tswana and the Xhosa. A smaller number worked on the history of the Khoekhoen and the Griqua. By the end of the 1970s these researchers had brought about a complete transformation in our academic understanding of the history of southern Africa from the late 18th century to the end of the 19th. In many cases, the PhD theses and published monographs which they produced in the late 1970s and early 1980s are still the prime sources on their respective topics. These works were based on readings of, on the one hand, long-existing colonial documentary sources and, on the other, newly available published sources (such as the James Stuart Archive in the case of Zulu history), and in some cases on the analysis of oral histories recorded in the field by the authors. They were also informed by new concepts – for example, homestead, house, lineage, chiefdom – and understandings of the structures of precolonial African societies acquired from the discipline of anthropology (which was undergoing its own transformation).

From the late 1970s-early 1980s, however, a new silence settled over precolonial African history as a result of three intersecting forces. The first was the Black Consciousness movement which vehemently rejected apartheid’s African homelands and which was consequently profoundly suspicious of engaging with the history of precolonial African states in case this lent a spurious legitimacy to homeland regimes. They preferred to emphasise relatively vague and generalised ideas about African achievement. Black intellectuals as a whole continued to hold to the established African nationalist stereotypes about the precolonial past as having been a Golden Age. They might accept new ideas about the importance of the Great Men of the precolonial past, but they strongly resisted arguments that precolonial African societies were not relatively egalitarian and democratic and that African states had been marked by oppression of a class of ‘have-nots’ by a class of ‘haves’.

In addition, in the early and mid-1980s, as political struggles in South Africa become more violent, academic research into the precolonial past largely gave way to what was seen as a more pressing need for research into the political, social and economic history of African societies in the 20th century. Numbers of historians who had been leading figures in the revolution in precolonial historiography moved into more contemporary fields, taking their research students with them. The main arena in which active research into the precolonial past continued was in the history of the early Zulu kingdom and its predecessor states. In this arena, a lively and at times acrimonious debate was sparked off in 1988 by the argument put forward by Rhodes University historian Julian Cobbing to the effect that the widespread upheavals of the 1820s and 1830s had been caused not by the expansion of the Zulu kingdom but by the broadening of the frontiers of slave raiding and trading from the Cape colony in the south and Delagoa Bay in the north. By the mid-1990s many historians had accepted the need to move on from long-dominant Zulu-centric explanations, but few were prepared to accept Cobbing’s formulations about the impact of slave raiding without major modification (see Hamilton 1995).

A third factor which initially invigorated but ultimately retarded research into precolonial African history was the influence of French structural Marxist interpretations of African society. These had a different kind of homogenising effect on views of precolonial African society from that produced by the Africanist propagation of the notion of the precolonial past as having been a ‘Golden Age’. In their view class divisions cut across and suppressed other lines of division in African society, rendering this kind of analysis often formulaic and drained of meaning to black and white scholars alike.

Over this period, it is probably true to say that Iron Age archaeologists paid more attention to History than historians paid to Archaeology. Shula Marks stands out as a lone voice in the wilderness, carrying on the old SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London) Africanist tradition which took archaeology seriously, and sought to comprehend what many other historians found to be arcane archaeological language and techniques. Her chapters in The Cambridge History of Africa were exemplary in this regard (Marks & Gray 1975; Marks 1985).

In the early 1990s South African politics was dominated by the manoeuvrings that marked the transition from apartheid to constitutional democracy. Among many historians, the expectation was that the establishment of a black majority government in 1994 would be followed by the active propagation of an African nationalist history, but in fact this did not happen. As is well known, there was instead a general turning away from ‘history from on high’ throughout South African society. The reasons for this have been widely discussed by historians, and will not be rehearsed here; the important point is that from the mid-1990s there was a sharp drop in the number of students studying history at almost all universities in the country, and in the standing of History as an academic discipline. Research into the precolonial past, already at a low ebb, came to a virtual standstill in History departments, though it continued in Archaeology Departments in uni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- Section 1 Disciplinary Identities: Methodological Considerations

- Section 2 Material Identities

- Section 3 ‘Troubled Times’: Warfare, State Formation and Migration in the Interior

- List of contributors

- Index