INTRODUCTION

Economy, ecology and labour

Devan Pillay

Twenty years after the start of democracy, the labour movement in South Africa, which has always sought to re-embed the economy into society, is now realising that this is insufficient – it also has to be re-embedded into the natural environment from which it draws its sustenance. This has long been realised by social theorists such as Karl Marx, who understood that both land (that is, nature) and labour are the sources of value (something both Marxists and non-Marxists in the twentieth century have completely misunderstood). In the 1930s the social democrat Karl Polanyi saw the dangers in the commodification of land and labour (through the so-called ‘self-regulated’ market) leading society to the edge of a precipice.

In other words, instead of what Ben Fine calls ‘economics imperialism’ – where the dismal science holds sway over all else – the economy has to be subordinated to society and the natural environment. The Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), and in particular its largest affiliate, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa), have produced policy papers over the past year that begin this journey of realisation. Jobs in the future have to be decent green jobs in industries that use renewable energy. Indeed, Numsa goes further and calls for a socially owned renewable energy sector, in recognition of the dangers that the ‘green economy’ embraced by our government – in keeping with the dominant global discourse – is little more than green neoliberalism, where large corporations seek to make huge profits out of the ‘sustainable development’ industry.

The National Development Plan (NDP), which impressively examines the full dimensions of climate change and ecological destruction brought on by incessant economic growth and consumption, ends up with policy proposals that effectively negate this insight. It gives primacy to the minerals-energy-financial complex – indeed, Cosatu views the economics chapter in the NDP as a leap backwards to the orthodox economics of the much reviled Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy, which has brought massive inequality, rising unemployment and persistent poverty. On labour issues the NDP mainly envisages the creation of low-paid informal jobs, and has no ambition to tackle social inequality. It is what the social analyst Jeff Rudin calls ‘symbolic policy’: pretending to understand the massive problems created by our economic trajectory, using the language of critics, but actually adopting a business-as-usual approach (with a few minor concessions here and there to labour, the poor and the environment). It is the classic art of paradigm maintenance.

In this section Nicolas Pons-Vignon and Miriam Di Paola examine the labour market during the democratic period, and conclude that labour market restructuring has failed workers. Instead, it has strengthened the gains made by white capital under colonialism and apartheid which the labour movement, they argue, has on the whole not countered. What is needed, they say, is a political economy tactic that takes class struggle seriously, instead of the timid approach that sees fixing education or promoting informal activities as a solution to poverty. Such a tactic requires a strong, united and militant trade union movement to put pressure on government (or, indeed, to help change the composition of government).

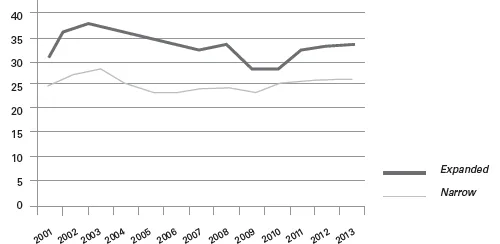

Ian Macun provides an overview of the state of organised labour since 1994, and asks whether unions have been significantly weakened in recent years or whether they still exercise influence over the ANC and government, and over employers through, for example, the extension of collective agreements such as in the clothing sector. He argues that it is necessary to look at different dimensions of power in the unions, including not only absolute membership but also union density, especially in specific sectors. For example, unions are very powerful in the energy, mining and public sectors, and overall retain a relatively high union density of around 30 per cent. Despite splits in some unions, Macun argues that unions remain very resilient, with deep organisational power, buttressed by a supportive legal and policy environment. As such they still exercise institutional power in the workplace and within national politics through the alliance with the ruling party.

Nevertheless, the Marikana massacre in 2012 highlighted the degree of social distance that has emerged between union leaders and the membership – including the critical interface between shop stewards and members. As some unions lose membership the key issues have become ensuring democratic workers’ control in unions and representing their members’ interests effectively.

Bridget Kenny looks at the case of Wal-Mart and the South African Commercial Catering and Allied Workers’ Union (Saccawu). The American retailer is well known for its low prices, which come at the cost of anti-union behaviour, low wages and minimal worker security. This leads to a form of ‘reverse Fordism’ where low incomes (as wages to workers, or squeezed prices paid to smallholder suppliers) feed the demand for lower food prices, leading to a downward spiral of working-class impoverishment. Saccawu played a major role in challenging Wal-Mart’s entry into South Africa, and received the backing of sections of government such as the departments of Trade and Industry, and Economic Development. The eventual settlement at the Competition Tribunal obliges Wal-Mart to support supplier development and to accept union organisation in its various retail outlets.

However, Kenny argues, the loud public debate around the Tribunal has no bearing on the real issues: huge inequalities within the food system, characterised by a low-wage, racist labour system. It avoids the critical questions about our developmental trajectory, based on the logic of food production for profit, which excludes the vast majority from active participation in a system of sustainable food security – an issue recently taken up by Numsa and the Food and Allied Workers’ Union (Fawu).

Jeremy Wakeford and Keith Gottschalk take us into other issues of sustainability, namely oil dependency and electricity generation respectively. Wakeford considers the risks inherent in the country’s dependence on imported oil within the context of general resource depletion and environmental degradation, the global production and consumption of oil, and the implications for oil prices. South Africa, he argues, has vulnerabilities in its liquid fuel-related industries, and should consider alternatives such as domestic liquid fuel production and a massive shift of bulk freight from roads to railways – and an overall shift towards public transit in cities and to electrified transport systems.

Gottschalk asks why the democratic government has been so enamoured with the atomic energy lobby. He argues against the easy explanation of corruption and clientilism and builds a case for highly skilful foreign and domestic nuclear energy lobbies, composed of bureaucrats, engineers and politicians, which have seduced successive administrations by appealing to atomic power as the ultimate political symbol and an aura of state power. The state has consequently ignored or downplayed cost-effectiveness, complexity and the potential for catastrophe. Gottschalk says that the focus should be on a mix of imported hydropower and gas, and solar power, which requires a major revision of the 2010 Integrated Resource Plan.

The power of the corporate lobby runs through all these chapters, illustrating yet again the manner in which the state has become enmeshed with the interests of corporate capital and not those of the people (despite the revolutionary rhetoric at party and union events). Indeed, as Marx argued, the state is increasingly becoming the executive to manage the interests of big capital, in the first instance, and of the people only when they make their voice heard. After twenty years of elite democracy, the workers, the poor and society in general are re-asserting Nelson Mandela’s deeper legacy: reconciliation with social justice.

INTRODUCTION

The liberation from apartheid generated great expectations of change in the workplace and the labour market (Pons-Vignon and Anseeuw 2009). This was due to the key role of trade unions – both as a political force and through successful undermining of the racist order which had been established in workplaces – in overthrowing the system of minority rule, (Von Holdt 2003). Apartheid geography had ensured the racial separation of dwellings. Encounters (often brutal) between people considered to belong to different racial groups took place, mostly in what Marx calls ‘the hidden abode of production’. The history of ‘forcible commodification’ (Bernstein 1994) of southern African peasants into wage labourers, one of extreme violence, was followed by the imposition of a migrant labour system and of colour bars (limiting the promotion of blacks) across workplaces, with the active support of the state and capital. In the absence of alternative sources of income, wage employment came to occupy a central place in the daily life (or reproduction, in Marxist parlance) of most South Africans; but with a record-breaking unemployment rate (standing close to 40 per cent), more and more research points to the restoration of employer power post-1994 through the widespread use of outsourcing and an explosion in casual and informal employment (Buhlungu and Bezuidenhout 2008; Pons-Vignon, forthcoming; Von Holdt and Webster 2005). The economically liberating stable employment to which most South Africans aspire has therefore not materialised but remains the overarching objective of progressive forces in which unions continue to play a leading role (Barchiesi 2011).

And yet, reading the media or the reports produced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), one could believe that the South African government has yielded to the dreaded sirens of populism, at least in the labour market. Rigid rules have allegedly been established, killing flexibility by over-protecting workers who are poorly skilled and over-unionised; a deadly mix which lies at the root of high unemployment and poverty (Klein 2012). Such arguments follow the South African (neo)liberal tradition (Knight 1982; Hofmeyr and Lucas 2001; Kingdon and Knight 2007) according to which the key to unlocking growth and reducing poverty in South Africa would be to reform the labour market (making it ‘flexible’) and equip poor people with useful skills. Similar arguments were used in the early 1990s to dismiss the report of the Macro-Economic Research Group (MERG, see Freund, forthcoming), and debunked by Sender (1994) who exposed their weakness. The new claims associated with this neoliberal perspective on the labour market suffer from serious empirical limitations, whether in attempts to point to ‘high’ wages as the cause of unemployment (Forslund 2013; Strauss 2013), or to claim that South Africa’s labour market is rigid (Bhorat and Cheadle 2007). This position is, however, reflected in sections of government, notably the National Treasury, which champions a ‘youth subsidy’ ensuring a transfer of taxpayer money to employers to facilitate the creation of casual jobs, and in the recently endorsed National Development Plan (NDP).

Such a perspective corresponds to a residual view of poverty (Oya 2009), according to which poverty alleviation requires a combination of free markets and improved human capital, and meaning that the poor ought to be equipped with what they lack, whether it is education or capital. The intrinsic inconsistency of such an approach has been captured by Amsden (2010) when she noted that Say’s law (supply creates demand) does not hold: increasing the supply of skilled workers will not alone generate sufficient appropriate jobs for them. Moreover, and crucially, the flawed characterisation of the South African labour market as ‘rigid’ has diverted attention away from a more grounded assessment of its performance. This chapter thus offers a critical review of post-apartheid labour market restructuring, showing that it has not failed for lack of flexibility, but rather because it has not protected poor workers. The changes which have taken place in the labour market have indeed reproduced, rather than challenged, the unequal relationship between capital and labour.