![]()

1.

Lizeka Mda

Dear Steve

Dear Steve,

It is amazing that it has been 30 years. Seems like yesterday that my eldest sister beckoned me from the playground to tell me: ‘Steve Biko is dead’; that the next day, 13 September, the Daily Dispatch carried a full colour portrait of you, and alongside it the words: ‘Sikhahlela indoda yamadoda’ (‘We salute a hero of the nation’); that it was not too long ago that an ox cart carried your coffin to the funeral.

Was it only 30 years ago that the farce that was the inquest into your death opened in Pretoria on 14 November; that the general public caught the first glimpse of such unsavoury characters as Colonel P J Goosen of the Port Elizabeth Security Police and the men who disgraced their profession by covering up for the police – Doctors Ivor Lang and Benjamin Tucker, district surgeon and chief district surgeon respectively for Port Elizabeth?

It was a time, however, when the likes of Sidney Kentridge, George Bizos and Ernest Wentzel served the legal profession with honour, representing your family.

It took a Supreme Court ruling to force the South African Medical and Dental Council to hold an inquiry into the conduct of the two doctors, in which they were found guilty of professional misconduct, in 1985. Much of the credit for that goes to Dr Wendy Orr, a very young doctor who was a subordinate of Lang’s.

Your death caused ripples in our world. The world outcry was such that the apartheid government was under siege and reacted the best way it knew, by banning a number of individuals, organisations (including SASO and the BPC) and newspapers on 19 October.

With all this name dropping you would be forgiven for presuming that I knew you or that you should know me. Not so.

I was a little girl when you died and was even littler when you were making your mark on this country’s political landscape. But I have made up for that by reading a lot about you.

To think that you were not yet 31 when you died. Yet you could come up with some of the insights you did, about black people, about the oppressive apartheid regime, about human nature, about the liberation movements and about the merits and demerits of capitalist and communist philosophies. Not to mention your understanding of Black Consciousness (BC).

I ask myself how you could have been so smart when you were 19, 22 or 30 and I do not have an answer. You are one of a trio I consider geniuses. You, like the other two, died so young, yet gifted humanity with a legacy for all time.

The other two? Martin Luther King Jr, who died in 1968 aged 39, and Bob Marley, 36 when he died in 1981. Geniuses. Which does not mean I don’t have questions about your reputations as ‘ladies’ men’.

What? That’s none of my business? You are my elders?

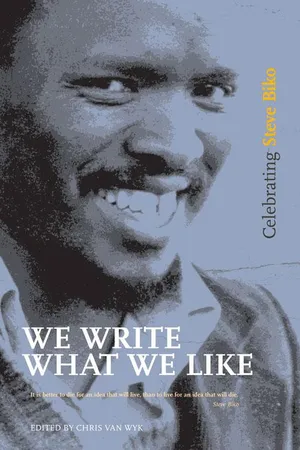

If you had lived, yes. But of course you know that you will be forever young, gifted and handsome.

If you lived during these times you might be surprised to find that people in their thirties call themselves ‘youth’. You would roll about laughing if you knew that, neh? We laugh too, otherwise we would have to cry, as it is not funny at all, just an excuse not to be responsible.

That way, these so-called youths can continue to make endless demands on society, dragging everyone along on a guilt trip so that should the ‘youth’ fall off the rails it will be society’s fault.

They obviously have no concept of what John F Kennedy meant when he said: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country!’ I want to believe you would be telling us the same now. Because, as Dr Mamphela Ramphele can tell you, instead of young people following your collective example when you set up clinics, such as Zanempilo, we have to import doctors from countries like Cuba. That’s because our own people are not prepared to serve rural communities.

What about the youth formations of established political organisations, I hear you ask. Surely these are the intellectual incubators of these organisations, or at worst, disciplined revolutionaries?

That’s what you think, Steve? The only way to use ‘intellectual’ in relation to this lot would be in the phrase ‘intellectually bankrupt’. ‘Disciplined’? Perish the thought!

You once said, ‘You are either alive and proud or you are dead, and when you are dead, you can’t care anyway.’

I hope you were right. For your sake anyway.

Otherwise you might be a little upset if you could see some of your ex-comrades. Ex? Yes! Many of them have sold out their principles and are permanent fixtures at the trough of greed and corruption that has engulfed our land. They remind me of ‘Hlohlesakhe’, the one who was only interested in stuffing his own stomach. Were you still alive when that drama was aired on Radio Xhosa? The belief then was that Hlohlesakhe was a parody of K D Matanzima.

Your decision back in 1969 to break away from the National Union of South African Students and form SASO resonated for many of us when we were university students in the 1980s.

But that was another place and another time. Then, one’s notice board had your picture sitting happily alongside those of Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe. It was a tolerant time when everyone’s contribution was acknowledged, and appreciated.

We live in a different time now. There is heavy reluctance to credit people like you and Sobukwe for your role in the struggle against oppression, colonialism, apartheid.

Sometimes I think it’s a good thing you died before you might have disillusioned us. Because I have to tell you, a fog of disillusionment coats many of the people we idolised then. In time they have proved to be men of clay – amadod’ omdongwe.

More often, however, I wish you were still alive. These are times when it seems that, had you lived, the philosophy of Black Consciousness would have taken deeper root; times when black people project such violent forms of self-hate one despairs for this country. Not only do we harm and kill each other as adults, we also live with the regular rape of infants. Evidently, we haven’t outgrown the things ‘the system’ taught us. Unlike you.

Of course you saw this dehumanisation of black people when you said: ‘Blacks under the Smuts government were oppressed but they were still men … But the type of black man we have today has lost his manhood. Reduced to an obliging shell, he looks in awe at the white power structure and accepts what he regards as the “inevitable position”. Deep inside his anger mounts at the accumulating insult, but he vents it in the wrong direction – on his fellow man in the township, on the property of black people…

‘All in all the black man has become a shell, a shadow of man, completely defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.’

Do you remember that self-help thing the Black Community Programmes ran? The self-reliance they taught? We’ve completely lost what that is about.

Now people build houses, neglect to put up water tanks and then cry: ‘The government must bring us water!’ Even when the government has built them houses, for free, the money that could have bought a water tank goes on things like giant television sets that fill up the tiny space.

Grown men see nothing wrong in appearing on television and crying: ‘Our local school has no toilets; we are waiting for the government to come and build toilets!’ I ask you...

And when the government does build those toilets, do you know that the cistern tanks and taps disappear in no time, into the homes of the very children who go to the schools? Did I mention before that black people can get on your nerves?

There is one person I have to credit for making you better known to me – Donald Woods.

As you well know, in the Eastern Cape of the 1970s, the Daily Dispatch was often the only source of information about what the Nats didn’t want known. And it was all thanks to the integrity of the man who edited the paper – Donald Woods.

He could very easily have chosen an easy life and pretended that all was perfect in this land. That’s what many editors did, and what many of us, faced with the might of the apartheid state, would have done too.

However, Woods was so moved by your discussions about what the BC movement sought to achieve – remember that first meeting when you summoned him to your office in King William’s Town? – that he gave up the easy road for the difficult path of pointing out that something was rotten in the land of B J Vorster.

And for his dedication in speaking out against your killing – in the process forcing Jimmy Kruger to drop the ludicrous ‘death by hunger strike’ story – he was banned, placed under house arrest and his family was harassed and eventually hounded out of their home and country.

Donald Woods’ Daily Dispatch one of the main reasons why I am a journalist today. My father bought it every day and it would eventually be recycled in our pit latrine in place of loo paper. So there were plenty of opportunities to read it.

Do you know that there were people who went out of their way to criticise Woods – claiming that he was using your name to build his own profile?

His Daily Dispatch introduced us to journalists such as Thenjiwe Mthintso, Vatiswa Ntshanga, Lulama Jijana, Charles Nqakula and Mono Badela. It was the Dispatch that introduced ordinary folk to another of your comrades, Mapetla Mohapi, who wrote a BC column for the paper. There was shock when Mohapi died in a Kei Road police cell on 5 August 1976 – according to his jailers, he ‘hanged himself’.

There was unease, but one also got the impression that there was a belief that ‘they’ wouldn’t go so far with a person with as high a profile as you. Surely they couldn’t believe they could get away with that?

How wrong everyone was. The Nats proved that there wasn’t anything they couldn’t do in defence of white privilege. They took just a year to dispatch you too. Part of the outrage over your murder was the carelessness with which a precious jewel like you had been handled; the thought of what had been done to you to cause the head injury and brain damage … to induce a coma; the idea that when the state doctors examined you, you were ‘naked, lying on a mat and manacled to a metal grille’; that with those injuries, you were dumped in the back of a police van, naked, for a 1 200 km journey to Pretoria.

And they brushed off the world’s disgust as if flicking off a fly.

‘Biko’s death leaves me cold,’ said Justice Minister Jimmy Kruger, while Prime Minister B J Vorster dared the world to ‘do its damndest’.

Black people, as you well know, can be a trial. They are often quick to criticise those who get off their backsides to do something, while they themselves are sitting in the sun.

That’s why they could throw stones at Woods for publicising your life and work, and exposing to the world what life was like for South Africans.

I had the joy of meeting and being befriended by Woods in the 1990s. I found him to be gracious and generous. He also had a playful streak, as when he would phone me and disguise his voice, speaking accentless isiXhosa. What a silly man! I liked him a lot and was sad when he died in 2001.

I had an opportunity to see your killers during amnesty hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Port Elizabeth in September 1997.

What is the TRC?

It’s too long a story, Steve. If you could, I would suggest you Google it. Suffice to say, it is one of the best things to have happened in this post-apartheid South Africa.

In his application to the Amnesty Committee, retired security police Major Harold Snyman blamed Colonel Piet Goosen, his commanding officer in 1977, for the instructions to keep you naked and to deprive you of sleep and food. Snyman said it was the same Goosen who had instructed the investigation team to lie about the circumstances leading to your death in statements to Major General Kleinhaus, who investigated your injuries, and to the inquest into your death.

As I reported in the Mail & Guardian of 12 September 1997:

Throughout Snyman’s testimony, his co-applicants Gideon Nieuwoudt, Daantjie Siebert, Johan Beneke and Rubin Marx, who were members of the interrogation team Snyman led, did not give any indication that they agreed or disagreed with their former colleague’s recall of events…

Nieuwoudt, on the other hand, alternated between staring into space while supporting his chin with his left fist, and looking around the hall as if trying to recognise people – his victims perhaps? He drank a lot of water and kept pouring water for Snyman....