![]()

1

“For the best ordering of the militia”

English Military Precedent and the Early Massachusetts Bay Militia

The 1628 Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company gave the company and its “chief commanders, governors, and officers” an order to provide “for their special defense and safety, to incounter, expulse, repell, and resist by force of arms” all enemies of the colony.1 The governor and General Court of Massachusetts Bay took this charge seriously, writing that it was as important to the success of the “City on a Hill” as their preparations for a godly church: “As piety cannot be maintained without church ordinances and officers, nor justice without laws and magistrates, no more can our safety and peace be preserved without military orders and officers.”2 As they established their own military system, New Englanders understandably looked to earlier English military practices for inspiration, both positive and negative.

The English Military Background

England’s military tradition of employing subject-soldiers to defend the realm had deep roots in the country’s history. The Assize of Arms in 1181 and the Statute of Winchester in 1285 both required all able-bodied men in England to keep arms for use in defense of the kingdom.3 England resisted the creation of a professional military even in the early modern era. As Europe underwent a military revolution in tactics and organization, brought about by the widespread introduction of gunpowder, however, the Tudor monarchs felt pressure to effect great changes in the English militia system, attempting to keep up with the standing armies of France and Spain. Mary Tudor (1553–1558) initiated a series of significant militia reforms, but she was unable to complete the job during her short reign.4 The urgent task fell instead to Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). While the law prescribed that all men between the ages of sixteen and sixty, with few exceptions, were required to keep arms for militia service, few of the men had any genuine training in the use of those weapons. England’s deplorable military condition was even worse when set against the ever-increasing professionalism of most European armies in the sixteenth century. With the hostility of Spain finally urging her to action, Elizabeth set about reforming England’s military establishment in the 1570s.

Although it was considered impossible to train every man in the realm adequately, Elizabeth retained the universal service obligation for every male subject in the general militia. In 1572, however, she established “trainbands” throughout the nation, issuing specific orders for their regular mustering and training. The queen and her advisers intended the new units to be made up of the more desirable members of society, including gentlemen, merchants, farmers, and sturdy yeoman—the men of the crucial, rising middle class.5 Elizabeth ordered the lords lieutenant in every county to acquire (from the general militia) “a convenient number of able men [to] meet to be sorted in bands and to be trained and exercised” in the new ways of war.6 The government even planned to distribute weapons based on class and ability, with those in the upper classes, “the strongest men and best persons,” given the best new weapons while “the least” would be given older, less complicated arms.7

The trainbands were defensive troops only, by law and tradition meant to serve only in England, not overseas or even in Scotland. Thus, for offensive forays in Ireland or on the Continent, England had to rely on impressments from the untrained men of the general militia, not the better sort from the trainbands. Numerous contemporary observers commented on the quality of men obtained this way. Writing in 1587, the military critic Barnaby Rich observed, “In England, when service happens, we disburden the prisons of thieves, we rob the taverns and alehouses of tosspots and ruffians, we scour both town and country of rogues and vagabonds.”8 A few times, the government even let men out of jail and shipped them immediately to the front as reinforcements.9 Thus, while in theory the Elizabethan reforms should have greatly improved the English military, in practice the institution was still largely untrained and ill-prepared, especially when compared to its European counterparts.

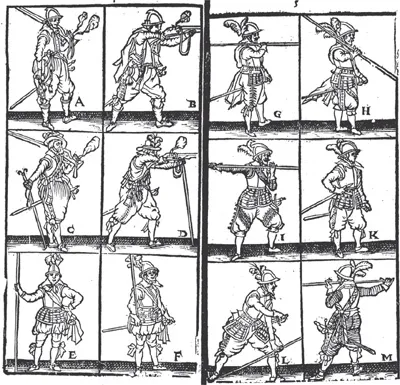

Figure 1. Woodcut from the English version of a French military manual, detailing several stances for the use of the matchlock musket and the pike. As England reformed its military forces, starting in the mid-1500s under Queen Elizabeth, such manuals became important for members of the new trained bands. Woodcut from The art of Warre by Sieur Du Praissac. Printed in Cambridge by Roger Daniel, 1642. Courtesy of the Birmingham Central Library, United Kingdom. Image published with permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

This system, ineffective but inexpensive, continued through the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I (1603–1625). With the coronation of Charles I in 1625, however, the military in England underwent another transformation. Whereas his father, James I, had expressed little interest in the military, the same was not true of Charles, who vowed to set up a “Perfect Militia.” Soon after his coronation, Charles dissolved the old, now corrupt trainbands (which had suffered a serious decline in social class). He set up new units with a property requirement for entrance, restoring them to the stable, merchant-based middle class as Elizabeth had originally planned.10 He also modernized all militia weapons and placed veterans in the trainbands to infuse firsthand military knowledge into the militiamen’s training.

Charles levied vast numbers of men for active military service; the number of soldiers impressed by Charles in peacetime was double that levied under Elizabeth in time of war.11 He also undertook several offensive military incursions and the armies for those expeditions caused considerable trouble back in England. Many soldiers, on their way to coastal towns to disembark for war, razed the English countryside. After the fighting was over, many army units, back in England waiting for their pay and formal discharge, spent their spare time pillaging English towns and villages.12 The people of England came to see their own army as the enemy, as dangerous to life and property as a foreign foe: “Men under arms had a fearful reputation among English people for casual violence, robbery, and rape and few events were viewed by villagers and townspeople with as much alarm as the arrival in the locality of a contingent of troops, friendly or otherwise.”13 The heavily Puritan East Anglia counties, where most English armies embarked (and returned) for overseas service, were especially distressed by this military abuse, something the East Anglians and their descendants would not soon forget.14 Worst of all, the system of impressment created feelings of deep distrust in the populace toward their own military. The men at the heart of this trouble were none other than Charles’s own lords lieutenant.

English Impressment: The Lord Lieutenant System

King Edward VI (1547–1553) appointed England’s first lords lieutenant in 1549.15 Before 1558, the English militia was organized on the local level, which led to great inefficiencies.16 With the Arms Act of 1558, Queen Mary reorganized the militia on a county basis, greatly strengthening the role of the lords lieutenant. Appointed by the Crown, the lords lieutenant became responsible for collecting tax money from the gentry and nobles for all military expenses, a fee known as “coat and conduct money.” They also had the task of levying, mustering, training, and inspecting men in their counties for active-duty service. By establishing the power of the lieutenancy, the monarchy removed the militia establishment, especially the impressment of men, away from local officials such as sheriffs and justices of the peace.17 At first, people in the countryside saw this as progress, because the local officials were often corrupt and saw impressment as the perfect opportunity to solicit bribes from common folk who wanted to avoid service.18 Yet, the lieutenants soon found that they had to maintain a delicate balance between the needs of the Crown and their own counties, a precarious situation that could jeopardize their standing in either community.19

The lord lieutenant was always a nobleman, often the most powerful man in his county. Many were also privy councillors with high connections at Court.20 Assisting the lords lieutenant were deputy lords lieutenant. Each county had two or three deputies culled from the foremost members of the local gentry.21 In England’s larger counties, the deputies had the requisite local knowledge and influence to ensure that the various duties of the lieutenancy were carried out. Even so, each had a large territory to control. Some counties also had muster-masters, professional, experienced soldiers who took charge of training the men and assisted the lords lieutenant in all things military. Rounding out the personnel of the system were local justices of the peace and sheriffs, who still retained a few duties during musters and troop levies. The power of these local officials, however, was on the wane. By the 1630s, local control had completely disappeared from the system.22 This lack of local control in Charles I’s “Perfect Militia” became a major concern of many of the Puritans who left England to start the Massachusetts Bay colony.23

Lords lieutenant and their subordinates oversaw the maintenance and training of the trainbands. The lieutenancy’s most important military function was to call up men to fight, either from the general militia for foreign military service or men from the trainbands for local defense in case of an invasion. This process of levying soldiers was the most complicated aspect of any lieutenant’s duty and required a whole host of actors, from the monarch all the way down to village constables. The process began when the ruler and Privy Council decided how many soldiers to call up and ordered each county to provide a set number of men. The Privy Council informed each county’s lord lieutenant of the number of men needed and the time and place of rendezvous. The lords lieutenant in turn informed their deputies; some lieutenants did nothing more than that, while some were very involved in the entire process.24

Typically, the deputy lieutenants did the real work of the press, first apportioning the number of soldiers to be levied from each town and village. They also had to collect money to equip and feed the men until they were turned over to the royal officers at the ports and transferred to

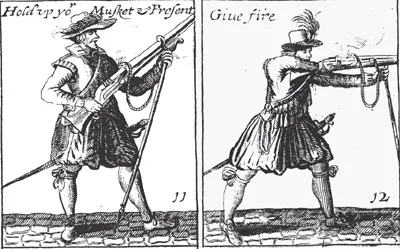

Figure 2. As most Englishmen had no experience with muskets, especially middle-class men from the country’s cities, military manuals were crucial to trained band members trying to learn the intricacies of the matchlock. These woodcuts show the proper stance and form for presenting and firing such a weapon. Woodcut details from The Military Art of Trayning by Jacob de Gheyn. Printed in London and “solde by R. Daniel” in 1622 or 1623. © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved C.27a21. Image published with permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.

the Crown’s expense. The deputies usually had the monumental task of choosing which men to press into service.25 They would then issue warrants for the local constables to deliver to the pressed men. It was at this point that the dual nature of the lord lieutenant system is most clear. The deputies (or lords themselves in some counties) had to balance their national duty—to provide the Crown with able soldiers—with their local affiliation and concern for their communities. Trying to maintain this delicate equilibrium was difficult and problems sometimes erupted, especially as Charles I began to centralize and nationalize the militia establishment.

The choice of who to press was greatly complicated by law and custom.26 Decisions on impressment also depended on the specific duty for which the men were required. Custom dictated that the sturdy yeoman of the trainbands stay in England. The trainbands had always been envisioned as containing the better sort of people in the country, especially “well-to-do householders, farmers, franklins, yeomen, or their sons.”27 These men were thus exempt from overseas service; they were needed for a strong home defense and no one wanted to endanger the country by their departure. The “better sort” were also the most likely to be able to afford and learn to use modern weapons, especially firearms. The trainbands, containing as they did property holders, were also considered more reliable if the Crown needed to put down an internal revolt.28 Some even argued that getting as many “masterless men” (those men most likely serving in the general militia) as possible out of London on overseas service lessened the chance of civil unrest breaking out in the first place.29

The preference given to the trained bands, however, caused two problems. First, it triggered a ru...