![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Inventing America: Expanding Industry

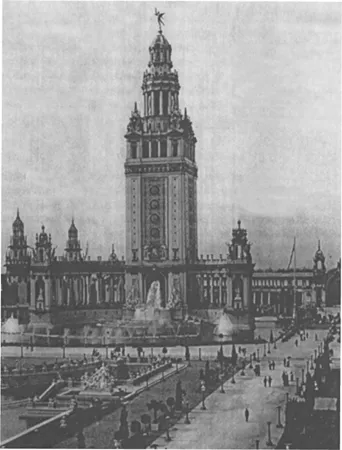

THE MOST spectacular building of the Pan American Exposition at Buffalo in the summer of 1901 was the central Electric Tower. It stood at the head of the Court of Fountains, rising 375 feet, “the high C of the entire architectural symphony.” Julian Hawthorne wrote in Cosmopolitan Magazine how “the shaft of the Electric Tower … assumes a magical aspect, as if it had been summoned forth by the genius of our united people … and it makes a tender nuptial with the sky and seems to palpitate with beautiful life.”

The exposition, known variously as the Rainbow City and the City of Light, was intended to look like a cityscape in oils lit by some splendid sunrise and, to a large extent, it succeeded. The whole exposition in general and its tower in particular were intended as a potent symbol of America’s industrial prowess and its largely untapped potential as a first-class world power. Thus it embodied representation and reality of industrialism, imperialism, and republicanism, all at once. Moreover, the tragic climax of the exposition strengthened people’s respect for these things.

The directors intended to draw visitors into the twentieth century that they projected as a Utopian era of rising prosperity and continuous peace. In an attempt to woo Latin Americans, with whom the United States wanted greater trade, the buildings were designed in the style of the Spanish Renaissance, not in white as with past expositions but in a myriad of colors. In particular, the exposition celebrated the contribution of railroads to the recent settlement of the West, the achievement of the American Industrial Revolution, and the superiority of white peoples over blacks, Indians, Hispanics, and Asians. All colonial exhibits, including those of the Philippines (a Filipino village) and Hawaii (with acquiescent subjects), were intended to justify American acquisition of new territories, to show that the results were ample compensation for the sacrifice of the war with Spain of 1898 and the subsequent suppression of the Philippine Rebellion (1898–1901).

The Electric Tower was to be the climax, representing “the crowning achievement of man,” and “dedicated to the great waterways and the power of Niagara (Falls)” whose water generated the current to illuminate and power the exposition. Mastery of the new technology of electricity made it possible to apply energy in precise quantities, wherever it was needed—something impossible in the old days of steam and waterpower. Electricity could light a house lamp, run a streetcar, work a sewing machine, and illuminate a skyscraper. Moreover, electric light could be transmitted for hundreds of miles, allowing manufacturing to choose the best sites for raw materials, labor, and transportation, rather than having to remain close to coal, water, or oil.

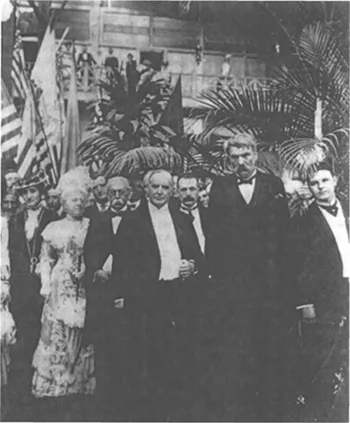

The expo directors intended the visit of President William McKinley on September 5 to be the supreme moment of self- congratulation but the plan miscarried. McKinley played his part beautifully. In his address on President’s Day McKinley praised such expositions as “time-keepers of progress,” praised industrial growth as the guarantor of progress, and proposed reciprocal commercial relations between the United States and the nations of Latin America. Expositions, he said, were important, because they set a record of material achievement, stimulated energy and enterprise, and gladdened people’s daily lives.

The next day, September 6, McKinley returned to the exposition. In the Temple of Music he bent forward to offer his usual red carnation to a little girl. He was shot at close range by an unemployed artisan, Leon Czolgosz. McKinley had noticed the young man with a bandaged right hand and, thinking it injured, had reached to shake him by the left. At this point Leon Czolgosz blasted him in the stomach with two bullets from a revolver concealed in a handkerchief—not a bandage. “I didn’t believe that one man should have so much service and another man should have none,” the assassin told his captors afterwards.

However, McKinley did not die immediately of the gunshot wounds in his stomach but of gangrene that set in and killed him eight days later.

On September 12 Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt, his family, and some friends decided to ascend Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks. While the others were dismayed by impenetrable drizzle on Friday 13 and decided to return to base, TR went ahead with one guide. He could not resist the highest peak in any region. Just before noon the fog lifted and the clouds parted and he could see right across New York State with its splendid mountains, trees, and sparkling water. Here Roosevelt immediately recognized the metaphor and reality of his position. Would he ever rise further politically or would the blanket fog of anonymity roll over him again? Would the peak of political office be forever denied him? The mists descended and Roosevelt went down another 500 feet to a lake, Tear-of-the-Clouds, where he ate a sandwich lunch. As he sat he noticed a ranger below running toward him with a yellow slip in his hand. It was a telegram and could only contain one message. TR set out for Buffalo immediately and arrived after McKinley had died. On September 14, 1901, Roosevelt took the oath of office in the same house where McKinley lay dead.

McKinley’s assassination exposed various divisions in American society along the lines of class, race, and ethnicity. Its very fact suggested something of the widening gulf between the huddled masses of immigrant workers and native artisans, dispossessed Indians and oppressed blacks, and the successful plutocrats of industry and finance, the politicos, and even the expanding middle class of professional men, progressive reformers, investigative journalists, and business executives. Czolgosz was a reputed anarchist. Although born in the United States, he was the son of Polish immigrants and this fact led to renewed calls for immigration restriction. Yet, paradoxically, the exposition with its trumpet fanfares of American industrial, democratic, and imperial supremacy, proved a means of maintaining cultural stability and confidence in the healing effects of progress at a time of acute political crisis.

The spectacular Electric Tower dominated the Pan American Exposition at Buffalo in 1901 by day and night. Its monumental presence was taken as a symbol of America’s industrial and imperial preeminence and a singular demonstration of electric power, the cheapest and most reliable form of energy yet known. (Photo by C. D. Arnold, Library of Congress).

Expanding Industry

The progressive generation of Americans who came to political maturity at the turn of the century, and among whom Theodore Roosevelt was preeminent, were sustained in their faith in political progress by the undoubted material progress of the American Industrial Revolution.

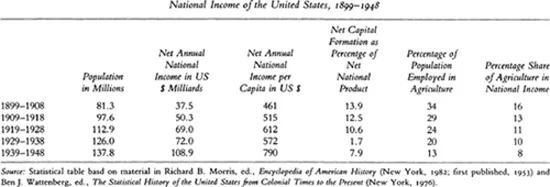

The extent of America’s industrial development in the first half of the twentieth century is suggested in the accompanying table, indicating population, net national income, and net per capita income (both in dollars, according to 1929 prices). The table also reveals the sharp fall in the percentage of the population engaged in agriculture and its declining percentage share in the national income.

The overall growth of industrial production in the United States (and in western Europe) was accompanied by a marked shift in the relative importance of various sections of industry and agriculture. Thus in the early twentieth century food and textiles accounted for 47 percent of total manufacturing production, whereas by the end of World War II they accounted for only 19 percent. In the same period metal products rose from 10 to 41 percent, while chemicals rose from 5 to 13 percent.

That America led the world’s agriculture and industry is suggested by export statistics that no other country could match. The value of American exports rose from $1.49 million in 1900 to $2.3 billion in 1914. Imports rose from $929 million (1900) to $2 billion (1914). During and immediately after World War I, American exports rose sharply from $2.3 billion in 1914 to $8.1 billion in 1920. They fell sharply in the recession of 1921 and the level fluctuated throughout the 1920s between a low of $3.8 billion (1922) and a high of $5.2 billion (1929). We might also note that in 1914 the United States’ principal trading partner was Britain, with Germany second, and Canada third.

There were five major keys to America’s astonishing industrial success: a superabundant supply of land and precious natural resources; excellent natural and manmade systems of transportation; a growing supply of labor caused by natural growth of population and massive immigration; special facility in invention and technology; and superb industrial organization. Thus what brought the American Industrial Revolution to fruition was human initiative, ingenuity, and physical energy.

The Agricultural Revolution hastened the Industrial Revolution in various ways. The increase in production per farmer allowed a transfer of labor from agriculture to industry without reducing the country’s food supply. Moreover, such expanding agriculture did not need the transfer of limited capital from industry to agriculture. Indeed, the profits derived from agriculture could be used for buying manufactured goods, thereby further stimulating industry and manufacturing. There were two manufacturing belts across the nation formed by the way cities were clustered. One stretched along the Atlantic coast from Maine in the North to Virginia in the South. The other was west of the Allegheny Mountains and north of the Ohio River, extending from Pittsburgh and Buffalo in the East to St. Louis and Milwaukee in the West.

By 1913 the United States was the world’s leading producer of coal, mining 500 million tons. American coal was cheaper to mine than any other, largely because its mines were shallow and surface open cast mining was much increased at the turn of the century.

There were two types of coal, anthracite and bituminous. Pennsylvania was the principal coal-producing state, accounting for 60 percent of total U.S. production. Anthracite coal was mined in a number of small fields in eastern Pennsylvania and coal was transported along the Delaware Valley on the Delaware River and its tributaries, and by canal and rail. Bituminous coal was mined in the west of the state in a region around Pittsburgh with its center at Connellsville that produced nearly all the coal used for coke in the United States. Illinois was second to Pennsylvania in coal production. West Virginia and Ohio also had coalfields that extended the Pennsylvania bituminous field and produced steam coal in the Pocahontas coalfield. Coal was also produced in the Appalachian states of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama.

Tragedy struck the Buffalo Exposition when its principal visitor, President William McKinley, (center), was mortally wounded by an assassin on September 6, 1901, the day after he had made a successful speech extolling American supremacy in industry, empire, and politics. Unconventional photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston took this conventional posed photo of the president’s party for the Illustrated Express. To the left of the president are Mrs. John Miller Horton (with parasol), and the Mexican ambassador; to his right are George Cortelyou and Col. John M. Brigham. (Library of Congress).

Whereas average annual coal production in the period 1896-1900 was 202.8 million tons, in the period 1906–10, it was 405.9 million tons. Moreover, this trend toward ever greater production continued during a period when world coal production was decreasing. Thus American production rose from 509 million tons in 1913 to 611 million in 1918, while world production fell from 1.32 billion tons in 1913 to 1.15 billion in 1919, partly, it must be admitted, because of economic dislocation in World War I. Only in 1919, when the United States’ economy was disrupted by a series of strikes, including a coal strike, did American production fall briefly to 486 million. Furthermore, American coal resources seemed almost limitless and it was estimated at the Twelfth International Geological Congress of 1913 that U.S. coal reserves amounted to 1.94 billion tons altogether. At the turn of the century about 681,000 men worked at the mines, both above and below the surface, mining on average 596 tons each per year, in comparison with Britain, which had to employ a work force of 953,000 men who extracted, on average, 275 tons each per year. This was because American mines were easier to work and American equipment was superior to British. In the period 1906–10, the bulk of American coal was for domestic use. Average consumption per head of population was 4.43 tons. American coal exports were 12.85 million tons, compared with Britain, which exported 83.57 million tons.

The United States was also rich in iron ore that was abundant, well distributed, and of excellent quality. The only disadvantage was that most of the ore was some distance away from smelting fuel. About three-fifths of the iron ore produced in the United States in the early twentieth century was from the Lake Superior region. It came from the Marquette Range, Michigan, discovered in 1855; the Menominee, south of Marquette, discovered in 1877; the Gogebic, Wisconsin, discovered in 1865; the Vermillion in Minnesota, discovered in 1884; and the Mesabi, also in Minnesota, discovered in 1892 and considered the most important of all.

It was also easy to extract. The ore was buried beneath a mere skin of glacial drift that just needed to be stripped for the ore to be dug and extracted and then transported. The Mesabi iron range turned out to be the world’s greatest field of iron ore. By 1900 it was yielding a third of all the ore mined in the United States, a sixth of the world’s supply, and half of all the raw materials to make steel. The development of the Mesabi field led to the construction of new steel works by United States Steel at Duluth, Minnesota. In the 1880s the iron and coal fields of the Appalachians were also developed. Both Pittsburgh to the east and Birmingham to the south became centers of the iron, coal, and steel industries.

As is well known, the iron and steel industry was highly centralized and thirty-eight plants of U.S. Steel were sited along twenty-six miles of navigable waterways. The very center of the iron and steel industry was Pittsburgh, partly because it was a traditional center close to coal, and partly because haulage was relatively cheap. It was most accessible to other regions, being sited at the union of two rivers to form the Ohio River. Pittsburgh produced a quarter of all pig iron in the United States, although most of its ore came from Lake Superior since its local supply had ended. Ohio and Illinois were the next largest centers of the iron and steel industry and both used ore from Lake Superior, except that plants in southwest Illinois used ore from Missouri close by.

In the 1910s and 1920s northern Alabama was a growing area for iron production, with an industry centered on Birmingham close to deposits of iron ore and coal. However, its ore was used only for foundry iron, not steel. Alabama had the economic advantages of cheap black labor and deposits of limestone that were used in the iron-producing process. Besides Birmingham, the towns of Bessemer, Sheffield, and Anniston also produced iron and Anniston had the most extensive manufacture of cast-iron pipes. In the period 1901–9 the output of steel products rose from 10 million to almost 24 million tons, with open-hearth steel exceeding Bessemer production in 1908. In 1909 open-hearth production was 14.49 million tons, while Bessemer production accounted for 9.33 million tons. The abundance of steel led to elaborate engineering projects by way of massive bridges and highspeed rails, battleships, trains, and eventually automobiles and airplanes. World War I stimulated greater steel production. The total number of steel ingots and castings rose from 23.51 million long tons (1914) to 45.06 million long tons (1917).

In the 1900s coke became the principal fuel in the steel industry. Moreover, in World War I enlarged demands for munitions placed a premium on the construction of by-product coking ovens to provide coal tar for explosives. By 1919 by-product coke amounted to 56.9 percent of the total of 44.2 million tons.

In the West the Rockies and Sierras contained large deposits of metals, both precious (such as gold and silver) and industrial (such as copper, zinc, and lead). Of the precious minerals, gold was produced at Cripple Creek, Colorado, and silver from Colorado, Montana, and Nevada. Aluminum, used in the making of electrical equipment and aircraft, came from bauxite, obtained in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, and Tennessee, and was usually produced by electrical furnaces. Because World War I increased the demand for alloys, it stimulated the aluminum industry. To meet the needs for special alloys, electric furnace production was greatly expanded, rising from 27,000 long tons of aluminum in 1914 to 511,693 long tons in 1918. Since the production of aluminum required large supplies of cheap electricity in the period 1900-20, the aluminum industry was often sited near hydroelectric power stations, such as those at Niagara Falls, Massera, and Long Sault Rapids, New York.

Petroleum

Between 1900 and 1920 the petroleum industry grew rapidly in a region of oil fields, stretching across a 160 mile strip, running from southwest to northeast in western Pennsylvania and New York and only 40 miles wide at its broadest point. The strip included 20,000 wells, pipelines, and refineries, and the petroleum extracted was used in various industries, such as iron-smelting, and manufactures, such as glass-making, in the same region.

At this time any manufacture was usually sited near its raw materials and source of energy. Thus in 1885 this particular region produced 95 percent of petroleum. From 1900 its yield began to decline, although overall American production of petroleum continued to expand. Fuel oil production rose from 300 million gallons (1901) to 1.7 billion gallons (1909). Petroleum benefited from the creation of an enormous new market after the turn of the century, created by the automobile. The new demand for gasoline fuel occurred almost precisely when the dramatic increase in electricity for light was rapidly reducing the demand for kerosene. Moreover, just as new markets for oil were being created, great sources of additional supply were being discovered in such states as California, Oklahoma, Texas, the Lima field in northeast Indiana and northwest Ohio, Kansas, and Illinois.

The modern period of oil production opened on January 10, 1901, when the Lucas well at Spindletop, near Beaumont, Texas, yielded a huge gusher. For each of nine days before it was capped it yielded between 70,000 and 110,000 barrels. We can understand the hysterical enthusiasm with which the strike was greeted by recalling that the railroads provided special trains from New York and Philadelphia for oil prospectors and, within a year, 500 wells had been sunk in an area of no more than five acres. In its second year of production the Spindletop well produced 17.50 million barrels.

The strike at Spindletop was the first indication of a huge oil boom in the Southwest. Other strikes and wells followed in Texas at Powell (1901), Sour Lake (1902), Petrolia (1904), Beaver Switch (1909), and Bunkburnett (1912). Moreover, the new state of Oklahoma (admitted to the Union on November 16, 1907) yielded vast supplies at Red Fork (1901), Glenn (1905), Cushing (1912), and Healdton (1913). Soon the yield in Oklahoma surpassed that in Texas and in 1907 Oklahoma was the leading oil producer of all the states; by 1913 it produced a quarter of the nation’s oil. Other pools were discovered in Louisiana at Jennings (1901), Anse-la-Butte (1902), Caddo (1906), Vinton (1910), Pine Prairie (1912), and De Soto (1913).

These surprise boom pools were attended by a great herd of wild-cat prospectors, well drillers, and sharpers. Eyewitness Samuel W. Tait, Jr., observes in his The Wildcatters (1946), “Never before was a region assaulted by so numerous, desperate, determined, and plunging an army of wildcatters.” Shantytowns appeared and disappeared overnight but some new towns prospered, including Tulsa and Port Arthur.

Because of its spectacular growth in...