![]()

PART I

Chinatown, Chatham Square, and the Bowery

AT ONE TIME, historians assure us, the Bowery was actually respectable. When “De Bouwerij” (Old Dutch for “farm”) was still a country road leading from the settlement of New Amsterdam to Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s estate near what is now Astor Place, it presented a bucolic scene of trees and fields. During the later revolutionary period, it formed a section of the post road to Boston, and thus became populated with inns and taverns such as the Bull’s Head, south of what is now Canal Street. Then for several decades, around the time the 18th century passed into the 19th, well-to-do merchants such as Edward Mooney—whose house, begun in 1785, survives at number 18—made the Bowery their home. As mentioned, the Bowery Theater, located between Bayard Street and Canal, opened in 1826 as a showplace for these prosperous citizens, importing refined English and European drama. This phase of the theater’s life did not last long, however: in 1830 its owners installed a new manager, actor Thomas Hamblin, who would find greater success with melodramatic fare such as Black Schooner, described in an 1839 playbill as “a new Nautical Drama founded on the late extraordinary Piracy! Mutiny! & Murder!” According to historian Theodore Shank, Hamblin’s contribution lay in realizing that a three-thousand-seat house could not be filled nightly by members of the carriage trade alone. Instead, through capitalizing upon a demand for “native” American talent, Hamblin brought in a working-class, largely Irish (and anti-British) audience, and thus helped pioneer the concept of New York theater as populist entertainment.1

The success of the Bowery Theater represented an early case of a New York entertainment space contributing to a larger pattern of social change. By the 1840s, as a street and a neighborhood, the Bowery had emerged as a predominantly working-class district, characterized by identifiable New York types such as the “B’hoy” and “B’gal.” In a manner not unlike the flappers or beatniks of later generations, B’hoys and B’gals set themselves apart through habits of dress and personal style. The men, sporting tall black hats and distinctive “soap-locks”—in which the hair was combed forward and plastered with soap—assumed a manner described by historian Edward Spann as “rough, boisterous, pugnacious and irreverent.” Generally Irish in national origin and affiliated with the city’s many volunteer fire-fighting companies—a municipal fire service not being established until 1865—they imbued the Bowery with a fresh and picaresque spirit.2

As a geographical stem of the East Side, the Bowery grew further with the waves of immigration that spread into lower Manhattan beginning in the late 1840s, particularly as thousands of Irish and Germans fled arduous and impoverished conditions in their home countries. Other immigrant peoples, including Italians and Jews, added to the mixture of languages heard on the Bowery—to the extent that, by mid-century, New York chronicler Charles A. Haswell could recall the street as having become “a very Babel.” Largely as a result of these demographic changes, the Bowery took on a popular image quite distinct from that of Broadway, its exclusive neighbor to the west. If Broadway was an elegant thoroughfare lined with stores and restaurants, the Bowery became known, in the minds of fashionable New Yorkers, as a disreputable place of odd smells, indecipherable tongues, and unremitting commercial activity on every day of the week, including the Christian Sabbath. In a manner similar to the apprehension with which some New Yorkers later viewed Harlem, much of the Bowery’s reputation for unwholesomeness probably was not fully deserved. In 1852 the New York Times hinted at this possibility in humorous fashion: “The Bowery mud is not a bit deeper, but fouler than the Broadway. The bricks falling from new buildings in the Bowery are not so frequent, but they strike harder.”3

It is somehow fitting that the Bowery grew during the mid-1800s as an entertainment district, a hub of theaters, concert halls, saloons and beer gardens. The entire street seemed pervaded by a carnival barker’s aesthetic reflecting uncannily the hyperbolic age of show biz entrepreneur, con artist, and circus founder P. T. Barnum. All of the Bowery was a show. In his book, Reminiscences of New York by an Octogenarian (1896), Haswell wrote of a visit in the 1860s to a Bowery seller of cut-rate merchandise (a “Cheap John”), who entertained patrons with the kind of nonstop patter that would later become a staple of the vaudeville stage:

“You wonder how we can sell so low,” said the Cheap John. “Why, exceptin’ rent, nothin’ costs us any thin’ besides paper. Paper costs enormous, ‘cause that’s cash, and we use up lots of it for wrappers. But the things we wrap up, them we never buy on less than four months, and when the four months have passed, so have we—we have passed on . . . ‘do good by stealth,’ as the poet says. Don’t go, gentlemen, going to have a free lunch at halfpast ten . . . just brought in another dog for the soup.”4

The Bowery’s déclassé reputation persisted throughout much of the 20th century, when it was known as the proverbial last stop on the way down—a world of flophouses, shelters, and single-room occupancy hotels like the long-established Sunshine at number 241. Inside the Sunshine, which is still open as of this writing, for $10 a night men sleep on cots in rooms that are six feet long, four feet wide, and covered with wire netting seven feet high. The tiny Sunshine provides a striking architectural contrast with the boxy, metallic New Museum, which opened next door to the hotel in late 2007. But despite its decayed nature, the Bowery, historically, has also been a place of tremendous vitality; a wide boulevard of vistas unobstructed by high-rises and, with its affordable rents, a haven for artists. Today little of the area is landmarked, and its many old buildings have become threatened by recent condo and retail development projects, such as the complex that replaced a famous dive of the 1890s, McGurk’s, and an adjacent 19th century beer garden in 2005. For decades the area survived as a kind of time capsule; now it is rushing to catch up with the rest of the city. Little effort has been made to balance growth with respect for history.

Still, there is much to be seen. On its lower end the Bowery merges with present-day Chinatown and terminates in Chatham Square. Chinatown, perhaps more than any other of Manhattan’s 19th century enclaves, has retained its character as a bustling, vibrant part of the metropolis. Although today this busy neighborhood extends far north of Canal Street and into Little Italy, its historic core is a small, triangular area dominated by three streets—Mott, Pell, and tiny Doyers—and bounded by the Bowery. This was the easternmost section of the infamous Five Points, named for the web of streets clustered near what are now the city courts buildings. Today this remnant of old Five Points is filled with memorable structures like the two small dormered buildings at numbers 40 and 42 Bowery. The latter was once a clubhouse for the Bowery Boys and Atlantic Guards, two of the warring factions memorialized in the book and film, The Gangs of New York. Early in the morning of 4 July 1857 a rival gang, the Dead Rabbits, attacked the house and its immediate neighbor, the saloon at number 40, with what the Times described as “fire arms, clubs, brick-bats, and stones.” The resulting battle lasted an entire week, entering legend as one of the bloodiest of the mid-19th century.5

Today the only violence occurs off-stage, as live crabs inside a tank in the front window are killed and served to patrons of the Chinese restaurant that inhabits number 40. Overlooked by many New Yorkers owing to the extremity of its distance downtown, Chinatown and lower Manhattan offer a range of similarly intriguing places to explore. When looking at buildings, here as elsewhere throughout the city, it is helpful to keep one’s eyes open for unusual and discordant architectural spots, those which seem to clash with their immediate surroundings. Buildings may hide their former uses with deceptive façades, but often one element—a piece of decoration or structural design—stands out, hinting at the presence of a treasure.

![]()

1

A Round for the Old Atlantic

ON THE LOWER Bowery, just across from the spot where an elegant Beaux-Arts sculpture announces the Manhattan Bridge, one of the city’s least acknowledged thoroughfares sits in repose. The “Chinatown Arcade”—words spelled in peeling white letters affixed to a red plastic sign—is largely hidden beneath the giant modern façade that squats above it, although traces of older, soot-covered brickwork remain near the sign’s edges. Inside, an air of discovery pervades the tight corridor, as pedestrians catch glimpses of wristwatch repairmen with tiny magnifying glasses affixed to headbands, Chinese pharmacists selling guidebooks on pointing therapy and moxibustion (oriental medicine therapies using, respectively, martial arts and mugwort herb) and rows of sturdy wooden drawers filled with roots and herbs. With a few restaurants thrown in, such as the long-surviving New Malaysian, the arcade is like Chinatown in miniature, a fascinating place that thrives despite the inattention of the rest of the city.

Once known as the Canal Arcade, it was carved out of the plot left behind by the old Bowery Theater, which burned down for the fifth and final time in 1929. It is still possible to get a sense of the theater’s enormity by strolling through the arcade, crossing to the other side of Elizabeth Street, which runs parallel to the Bowery, and looking back. From there the nondescript structure provides a ghostly outline of the building that helped define Manhattan’s cultural life for a century.

But the Bowery Theater is not the only numinous presence on this culture-steeped block. Immediately to the north of the arcade’s rear exit, on Elizabeth, stands a curious façade: two stories of russet-colored brick, topped with a small row of gothic arches carved in simple fashion. A quick stroll northward, toward Canal, offers a hint of something rounded behind the façade’s top edge, and from just the right spot near the southwest corner of Canal and Elizabeth that same curve appears to turn into a sharp peak. Then, obscured by tenements, it vanishes, leaving little suggestion of its purpose or history.

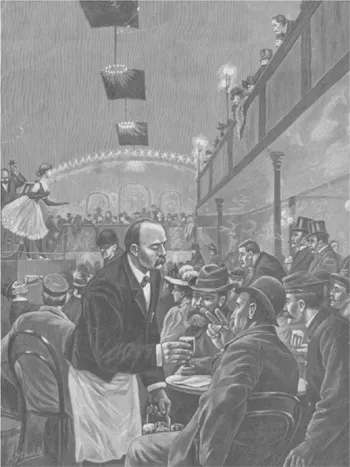

1.1. The Atlantic Garden during its vaudeville years, early 1890s.

Lost within a neighborhood that long ago abdicated its role as entertainment district, the peaked roof is a relic from days when German families crowded the Bowery on warm evenings, having crossed Chatham Square from their tenements on Catherine, Division, and other streets to the east. In long, spacious halls, the sides of which were decorated with trees, flowers, and other sylvan reminders of the home country, they would enjoy cold drafts of beer in “schooners” (dimpled glass mugs), while listening to the harmonious strains of female orchestras playing waltzes. Once the music stopped, everything would explode in an uproar of conversation, augmented by the twittering of birds suspended in cages overhead. The smells were pungent and appetizing—malted barley, tangy sausages, strong Limburger cheese—but nearly overpowered by the choking cigar smoke that rose toward vaulted ceilings in thick eddies. Waiters bustled past long, narrow tables carrying three schooners to a hand, and the entire atmosphere was one of frivolity and high spirits, of relaxation after long hours of toil.

Popular throughout the second half of the 19th century, bier gartens were unique combinations of concert halls and taverns where New Yorkers could drink and socialize while enjoying first-class entertainment. Of these, the Atlantic Garden at 50-52 Bowery, next door to the Bowery Theater, was the largest and most famous, surviving in its original form for more than half a century. Tourists made it their first stop when approaching the dissolute charms of the Bowery, and as the neighborhood around it acquired an increasingly dangerous reputation in the 1890s, the Atlantic clung to its respectability. It was the only “clean” establishment on the entire thoroughfare, testified hard-boiled Inspector Thomas Byrnes during an 1890 investigation into Bowery vice (one of many): “The other concert halls are the resorts of women of questionable character and men who come to visit them.”1

But even with its clean image the Atlantic was far from secure, coming under frequent attack from police housed, conveniently, on Elizabeth Street. Still, it managed to survive through the perseverance of one man, the founder and proprietor William Kramer, who fought murky legal strictures and the cops elected to enforce them for the bulk of his existence. From the Atlantic’s peak in the 1870s all the way through the Gay Nineties, few years passed without raids, arrests, and arraignments before the Police Court, housed in lower Manhattan’s infamous prison, the Tombs. The cause of Kramer’s trouble was a seemingly innocuous product, one that could be described as the source and spring of his livelihood: “the nectar of Gambrinus”—in German, Lagerbier.

Not yet embraced by fashionable New Yorkers of the 1850s and 1860s, who tended to prefer what one observer described as “whisky ‘cock-tails’” and other drinks associated with the “Anglo-Saxon American,” beer was largely synonymous with German life, a characteristic that fascinated travel writers of the period. Junius Henri Browne, writing in The Great Metropolis, a Mirror of New York (1869) offered a satiric account of what he viewed as an inherent trait:

The Germans are an eminently gregarious and social people, and all their leisure is combined with and comprehends lager. They never dispense with it . . . The chief end of man has long been a theme of discussion among theologians and philosophers. The chief end of that portion who emigrate from Fatherland is to drink lager, under all circumstances and on all occasions.2

German New Yorkers were portrayed in such accounts largely as hardworking and peaceable, their economic status as tradespeople and shopkeepers marking them in positive contrast to the working-class Irish. Even writers of a strict temperance mind-set, and therefore opposed to beer drinking of any kind, could not disguise an admiration for what were perceived as German qualities of industriousness. The Rev. Matthew Hale Smith, for example, whose observations were laced with racist and anti-Semitic commentary (of the Bowery he wrote, “The Jews are numerous . . . These men have no conscience in regard to the Christian Sabbath”), seemed to enjoy the Atlantic Garden in spite of its immorality:

The rooms are very neat, and even tastefully fitted up, as all German places of amusement are. The vilest of them have a neatness and an attractiveness not found among any other nation. The music is first class . . . A welcome is extended to every comer.3

William Kramer’s legal challenges seemed to rise, paradoxically, out of the very qualities of industry for which he and other German business owners were admired. Since Sunday was the only day when most German New Yorkers were not working—stores and businesses being closed—it was natural that they would spend part of it drinking beer and socializing at the Atlantic Garden. This habit, anticipated with pleasure throughout the long week, was a fundamental means of retaining the patterns of life in the old country. But it created problems by conflicting with state “excise laws,” akin to what have also been termed “blue” laws, prohibiting the consumption of intoxicating beverages on the Sabbath. Although Kramer was willing to make temporary concessions, on a larger scale he refused to be cowed, and pledged to continue dispensing the beverage upon which his livelihood was based. He was prepared for a long fight.

Germans, less memorialized than their Irish and Italian counterparts, were once one of New York’s most populous immigrant groups, numbering more than one hundred thousand by 1860 and increasing significantly in the following decades. Germans of varying religious and social backgrounds had begun coming to the United States in large numbers after the failed revolution of 1848, which created large-scale suffering and economic hardship in their home country. When William Kramer arrived in 1854 he was no different from most of his countrymen: no money, no friends, and no family connections. But the twenty-year-old newcomer had ambition, and he found various jobs selling shirts, grinding coffee, and working as an assistant cook before landing as a bartender in the Volks Garten. Perhaps the earliest of the German beer-gardens, the Volks, or “People’s Garden,” was then located on the east side of the Bowery, between Bayard and Canal Streets. Kramer’s tenure there was brief, but it gave him enough time to build a plan that would, in time, make him one of his adopted country’s most prominent German citizens.

In the late 1850s a famous tavern on lower Broadway, the Atlantic Garden (formerly the King’s Arms), was ending its reign as a landmark of old New York. It had enjoyed a tumultuous history, having been used as headquarters for General Gage, the commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, and later as a meeting place for the Sons of Liberty in the prelude to the Revolution. Acting in partnership with two other employees of the Volks Garten, Albert Hambrecht and Adolph Goetz, Kramer decided to borrow the old Broadway tavern’s name and give it new life on the Bowery. The site he chose lay directly across from the Volks, on a plot that had been at least partially occupied by another tavern, the Bull’s Head, which had served as George Washington’s temporary headquarters in November 1783. By Kramer’s time it was being used as a stove dealership with a large coal yard in back, and the partners were able to open shop with their total savings of $250 (about $7,500 in modern currency).4

The new Atlantic Garden was unveiled in 1858, with a saloon in front and a large tent in back for entertaining patrons during warmer months. Though much of the property could not be used during winter, the Garden became increasingly popular over the next few years, as Kramer and his partners began servicing the neighborhood’s growing German colony. Their first period of real success came during the Civil War, when Kramer, a Unionist, offered the Garden as a rallying spot for Northern troops. In early 1864 it was a banquet hall for returning members of the 58th and 68th regiments of General Grant’s army, and periodically throughout the conflict Kramer set up a portion ...