![]()

1

Race Formation and Morally Configured Black Identities

We the Rastafarians who are the true prophets of this age, the reincarnated Moseses, Joshuas, Isaiahs, Jeremiahs. . . we are those who are destined to free not only the scattered Ethiopians (Black men) but all people, animals, herbs and all life forms. . . . We are those who shall fight all wrongs and bring ease to the suffering bodies, and peace to all people.

(Ras Sam Brown, “Treatise on the Rastafarian Movement,”1966)1

One March afternoon in 1998, while sitting in a meeting convened by the Rastafari Federation in Kingston, Jamaica, I reflected on how the Rastafari use their identity to embody and engage the past while living in the present. Empress Dinah, a pecan-brown-skinned Rastafari woman in her late forties, sporting a steep, tightly wrapped crown of dreadlocks, stood in front of the audience on a low stage, with a microphone in one hand and notes in the other, addressing an attentive and largely male audience of approximately 70 Rastafari and a dozen non-Rastafari. Empress Dinah spoke about Blackness, injustice, and organizing the Rastafari into a confederation able to actualize their collective desires. What led me to reflect on the event were the opening lines of the Empress’s speech:

Greetings to our race and the people of Rastafari. . . . Rastafari must live the words and teaching and orders of His Imperial Majesty Haile I Selassie I. . . . Rastafari must fight against colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, ignorance, poverty. . . . [Rastafari must] Think and work I-electively [collectively] for all Rasta people.

A Rastafari elder, Ras Sam Brown, spoke after Empress Dinah. He delivered a critical and rousing speech that used the European Union as a trope for declaring the utter necessity of Rastafari people to come together as “one nation”—Europe should not, he suggested, set the example for “coming together.” Black people—Rastafari—should set the example. Ras Sam Brown was urging a Rastafari union. Like Empress Dinah, he used a language of defiance that drew on the rhetoric of fight and race: “Rastafari [is] forever fighting for Black liberation. . . . There is no higher reward than for a people to be called by their God to serve in the cause of Black liberation.”

Predominant themes in the talk of the Rastafari I met in Jamaica were race loyalty and disloyalty, allegiance to a Black King, hostility toward oppression and subjugation, the unceasing importance of liberation, the danger of miseducation, and issues of morality inseparable from race and religion. As I listened to them speak in the meeting, I thought about the lineage of their rhetoric and practice, the varied routes they traveled in becoming who they are, and how on the eve of the twenty-first century, a people who only four decades earlier were feared and despised, had become cultural exemplars of Blackness. In this meeting off the beaten path, held at a comprehensive school located in a chancy ghetto off Spanish Town Road, were a group of people engaged in conversations about race, justice, and identity that have their source in a past that is remembered and embodied in these and other Rastafari.

Blackness as a Durable Cultural Resource

To grasp the evolving identity and rhetoric of the Rastafari, we must look to the historical and social bases of the ideas and practices they use to define themselves and the cultural worlds they have forged. We must determine how and why ideas about race, God, deracination, oppression, and miseducation are so salient, and how such ideas have endured, spanning generations. Indeed, we must reveal the emergence of Blackness itself, how out of many African ethnicities, languages, and differences a “generic” Black identity supersedes these particularities. Ethnogenesis is about the emergence and development of new groups, and to fathom this process, we must identify the cultural resources that people draw upon as a part of identifying with a particular collectivity (I expand on ethnogenesis in the next chapter). We must simultaneously consider Jamaica’s distant and not-so-distant past, identify key actors and moments involved in the forging of cultural resources, and consider the ways in which those actors used resources to express their identity.

In Jamaica, morally configured Black identities like Rastafari draw deeply upon the cultural resources of racialized moral economies. These are cultural artifacts created and reinforced through Black people’s experience of uprisings, reprisals, dashed hopes, marginalization, and a strong desire for better and for building genuine communitas. As we shall see, Jamaican moral economies of Blackness are informed by a racialized set of themes and values I call justice motifs: truth, righteousness, freedom, liberation, autonomy, and self-reliance. These justice motifs are used to articulate grievances and alternative visions of their world. People racialize these motifs through enculturation—personal experience, stories, observation, instruction, collective memories and representations, and through interaction with other people. Race—Blackness in this case—can be put to many uses; it can provide a sense of affinity and security, and furnish a framework for interpreting the past, present, and future. Indeed, the identity work of the Rastafari will illustrate how ideas of race endure and why it is so salient to some people.

To describe cultural resources as artifacts does not limit them to material element; they include ideas as well. We make cultural artifacts in practice—in doing, generating cultural and social worlds (Bartlett & Holland, 2002; Holland & Lave, 2001; Holland, Lachicotte, Skinner, & Cain, 1998). In a given cultural world some images, people, stories, concerns, and memories are more salient and more meaningful than in other cultural worlds. The sentiments and emotions that things in a figured world evoke are important in the motivation they provide and the contribution they make to remembering (Strauss & Quinn, 1997:118; Cattell & Climo, 2002). Slavery and acts of injustice, for example, are important emotive images in the formulation of Blackness that I explore in this book and that infuse Rastafari identity. Not every Black Jamaican is influenced by, interested in, or aware of these concerns regarding Blackness, or even race in general. However, as cultural forms, they are there for people to discover and embrace, accidentally or purposefully.

As my narrative unfolds, I ask the reader to keep in mind oppression, deracination, and miseducation, because these create the context for the need and desire to create positive and historicized affirmations of Blackness. My voice will dominate the first part of this chapter as I frame the history that is a part of the Rastafari. My narrators will enter the story later in the chapter.

The Morant Bay Rebellion: Blackness and the Moral Economy

How did Blackness become a salient identity in Jamaica by the 1860s? And how did it become intertwined with religion and morality?

We begin in a contentious moment and place—1865 and Morant Bay—where Jamaicans unambiguously displayed a rebellious and morally configured form of Blackness. We shall then determine important antecedents to the Morant Bay outburst before moving to identify important episodes and contributions that together provide a well of cultural resources that the earliest Rastafari draw from as they begin their work of building a collective identity.

On October 11, 1865, Paul Bogle, a Black Native Baptist preacher, led two, maybe three, clamorous groups of several hundred men and women into the town of Morant Bay. They marched in formation, armed with sharp implements, beating drums and blowing conch horns. Their attention was fixed on the courthouse where the parish Vestry, the local political body, was holding its regular meeting. The urgent concern of the insurgents, however, was disabling the local police, which they did handily (Heuman, 1994). The insurgents were willing to risk violent confrontation with the townspeople because of the accumulated grievances they held against the planters, the Vestry, magistrates, debt and tax collectors, and the police. The insurgents, mostly agricultural laborers and small farmers, knew they could not obtain a fair hearing in the courts; they feared they were about to lose possession of their provision grounds; and they were onerously taxed to offset the losses of the planters. There were other concerns, too, such as frightful rumors that they were going to be re-enslaved. The insurgents identified powerholders and elites—mostly Whites—as threats to their livelihood and well-being, and as violators of what they interpreted as a right to use land, make a living, and get a fair hearing in the courts. These were some of the primary causes leading to the rebellion.

Consider some of the racial rhetoric observers of the event claimed to have overheard the insurrectionists use: “We will kill every white and Mulatto man in the Bay”; “It is your colour [Black]; don’t kill him. You are not to kill your colour”; “So help me God after this day I must cleave from the whites and cleave to the blacks” (Heuman, 1994:4–5). A vivid sense of justice animated their racial awareness. The rebellion epitomized the capacity of race and a moral economy of Blackness to mobilize people who otherwise might not have challenged an oppressive social order, an order that they might have considered hopeless or preordained.

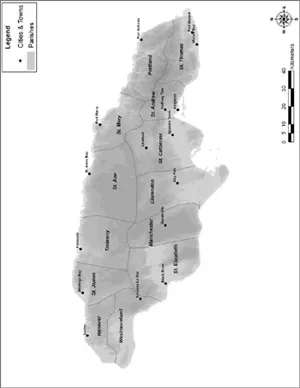

Map of Jamaica

Considerable diversity in experience and social position characterized Black Jamaicans of the 1860s. Charles Price (no relation to me as far as I know), for example, was a well-known and well-off Black Jamaican who apparently identified firmly with Jamaica’s White ruling class. Indeed, his advantageous position was based on his connections to Whites and Browns and the continuation of the social order that benefited Whites. Price’s complicity with the oppressive order was already understood by the Morant Bay insurrectionists. During the fray, Price harbored some of the Whites who were the targets of the crowd, and his assistance cost him his life. Nonetheless, the decision to kill Price illustrates the complexities involved in understandings of Blackness. On the one side, the crowd noted Price’s multifaceted identity: “Price, don’t you know that you are a black nigger and married to a nigger?. . . Don’t you know, because you got into the Vestry, you don’t count yourself a nigger?” Price, perhaps seeking to save his Black skin, agreed that he was indeed a “nigger” and offered £200 to save his life. But then a woman pointed out Price’s support for the White racial order and how he had worked Blacks without paying them. She recommended a death sentence. Another member of the crowd pointed out that Price had “black skin and a white heart” (Heuman, 1994:9, 10). Price was beaten to death.

More than a century after the Morant Bay rebellion, metaphors of heart and race loyalty continue to serve as cultural resources. The idea remains that a person’s “heart” can describe their moral and racial commitment. For example, many Rastafari use the heart as a metaphor for discerning a person’s deepest values and commitments; to be “heartical” is to be morally upright, respected, and perhaps even racially conscious. There is also the mythical “Blackheart man,” a shadowy and dangerous bearded figure believed to eat living human hearts and abduct children by enticing them with sweets. The modern Blackheart man drove around in a black car. Mere mention of “Blackheart man” could make the knees of children knock, and adults might suspiciously eye any lone or unfamiliar bearded man. The Blackheart man was evil, and he was Black. The Rastafari were called Blackhearted, signaling danger and depravity. Bongo J said, “In them times [the late 1930s] there was no Rastaman deh [there] ‘bout. . . when you see one man is a Rasta man you run.” “Why would you run?” I asked. Bongo J’s face frowned, his eyebrows arched, and his voice rose: “How you mean? Intimidation! Them say him blackheart and a kill pickney [children] . . . listen to me . . . if I a pass through right now, pickney a run from me, man!” (Bongo J).

The two main instigators at Morant Bay were George William Gordon, a Brown minister who was a radical politician and wealthy landowner, and the Black minister, Paul Bogle. Both were affiliated with the Native Baptist Church, an important site for the construction and dissemination of morally configured Black identification. George Gordon was born around 1820 to a slave mother and White attorney father. Although Gordon was born a slave, his father granted him freedom and paid for his early education (Holt, 1992:292; Heuman, 1994:63). Gordon became a self-styled defender of the poor, and converted to the Native Baptist faith in December 1861. As a politician he put himself out on a limb among his White colleagues because of his candid arguments against the racial practices of the Colonial government.2 Because Gordon so closely participated in Blacks’ lives, elites viewed all his activities with great suspicion and doubted his loyalty to “his kind.” His racial identity—Brown—complicated matters because he had an opportunity to distance himself from the majority, poor Black Jamaicans. Browns, during Gordon’s lifetime, were almost always the offspring of a White man and a Black woman.3 They have constituted a significant presence in Jamaica for most of its history, even though they have always been a small racial minority.4 Even though Browns could be born into bondage, they often received preferential treatment in the form of lighter workloads and access to education and trade training. Within Jamaica’s racial landscape, both White and Brown were understood as superior to, and the antithesis of, Black (Alleyne, 2002). Not all Black Jamaicans accepted this hierarchy that debased them. By the time of the Morant Bay rebellion there were competing views of Blackness—a valued and a devalued identity—and over time the esteem given to Blackness has increased to where today its positive valences are so widely acknowledged that it seems Jamaicans have always appreciated it.

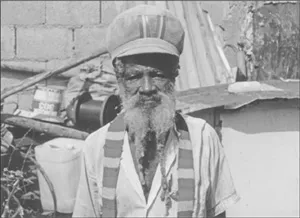

Bongo J, born in rural St. Catherine in 1931. Introduced to Garveyites during the late 1930s. Began conversion to Rastafari in the late 1950s and grew out his beard in 1961.

We know little about the early life of Paul Bogle. He lived in the Stony Gut community, not far from Morant Bay, and it appears that Gordon baptized and ordained him as a Native Baptist minister (or a deacon) in 1865 (Barrett, 1988:58). Like Gordon, Bogle acted as an advocate for the Black poor. Indeed, Bogle was involved in a range of alternative racial institutions, such as Black courts. These courts were extra-legal institutions that handled disputes between Black citizens because they could not expect justice within the formal legal system.

The day after insurgents marched on Morant Bay, October 12, soldiers seized the nearby town of Bath, and Maroons entered the fray on the side of the Whites (more on the Maroons below), turning the tide against the Black insurgents. The White local militias, vigilantes, and British soldiers did not stop at neutralizing the insurgents. They initiated a massacre against local Blacks, slaughtering hundreds and burning more than a thousand homes. The insurrection and the White response to it led Britain to re-take control of the island, making it a Crown Colony government.5

Moral Economy of Blackness

At the time of the Morant Bay rebellion, there were Black Jamaicans whose sense of moral righteousness and justice had found validation in the Bible story of the journey of the Hebrews out of bondage in Egypt and into the Promised Land. As it has done for many oppressed people (Walzer, 1985; Wilmore, 1998), the story of Exodus caught and held the attention of Jamaican slaves. Other biblical passages spoke forcibly. Psalms 68:31, “Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God,” no doubt offered consolation and hope with its promise to redeem God’s Black children. James Phillippo, a White Baptist missionary active in Jamaica during the early to mid-1800s, wrote that it was not uncommon at the time to find Black slaves identifying with Ethiopians and Israelite captivity in Egypt (1971:143, 148).

During the Morant Bay rebellion there was almost no looting. The “mob” attacked the symbols and embodiments of oppression: the police station, the Vestry, the courthouse, the Custos, tax collectors, and exploitative planters. By 1865, there had developed a moral economy that valued racial solidarity. During the week of rebellion the insurrectionists defended and asserted a moral economy of Blackness.

As James Scott (1976) has argued, a moral economy describes people’s beliefs that they have a “right to subsistence.” Because a moral economy involves cultural ideas, participants may not privilege it as a distinctive feature of their lives, or they may take it for granted as a part of “who we are.” Outsiders might remain oblivious to its presence, but by identifying what constitutes local norms of social justice and what is considered injustice and exploitation, we can make out the contours of a moral economy (Scott, 1976:11, 32, 41). Thus, rebellion and protest can signal more than mere reaction; they are ways in which collectivities demonstrate their rights, especially to livelihood and identity. The moral economy of Blackness points us toward racialized and valued ways of life that include ideas about social welfare, tradition, community, and identity.

For the Morant Bay rebels, injustice was located in the hands of White planters and administrators and the Blacks who supported and emulated them. Land policies figured prominently in the insurrectionists’ moral economy. Many Blacks in the parish had inadequate or no access to land, no avenue to move from abject poverty. Taxes, too, affected subsistence. Whenever market shifts or policy change in Britain (in this case, the end of protection for Jamaican sugar) negatively affected planters and other members of the dominant groups, they recouped some of their losses by taxing the predominantly Black and poor citizenry and by reducing wages. From the perspective of many rural Blacks, these practices were unfair and raised the specter of a slide back toward slavery. Thus, by 1865 there had evolved a racialized cluster of ideas about justice, righteousness, freedom, liberation, and truth that were connected to concerns involving land, work, livelihood, subsistence, and identity. We must add redemption—deliverance from bondage and oppression—to our cluster of justice motifs. The justice motifs and the moral economy of Blackness were more than abstractions; they found their motivating power and appeal in lived experience, memories, cultural resources, and the sentiments connected with these. Their resonance, if anything, increased over time. Sixty-five years after the Morant Bay rebellion, Leonard How...