![]()

1 The Black Sailor

Chambermaid to the Braid and Nothing More

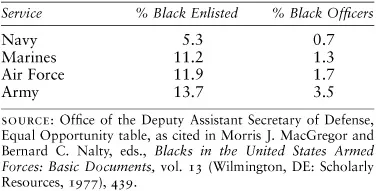

During the early 1970s, most black sailors viewed the Navy’s record on race relations with a profound sense of skepticism. As of March 1971, blacks accounted for only 5.3 percent of the Navy’s enlisted personnel and a mere 0.7 percent of officers. By contrast, their representation in the other services was much more substantial. “The figures made it clear,” Admiral Elmo Zumwalt wrote in his memoir On Watch, “that as far as breaking down racial barriers was concerned, the Navy was marching in the rear rank of the military services.”1 The reasons for this disparity were deeply rooted in the history of the service and the nation at large.

The history of African Americans in the U.S. Navy can be traced all the way back to the nation’s colonial roots. Black seaman often served on Royal Navy ships and privateers well before the onset of the War for Independence. During that subsequent war, African Americans continued to serve the British cause, especially after the royal governor of Virginia, John Murray, issued a proclamation promising freedom to slaves who fought with the loyalists. Hundreds of slaves used small boats and watercraft to escape slavery and volunteer their services to Royal Navy vessels in the Chesapeake Bay.2

But African Americans also joined the fledgling American cause. It is impossible to know how many African Americans served in the various American navies during the American Revolution. Some historians have suggested that the number could be as high as 10 percent of the sea services. Whatever the case, black sailors fought not only in the Continental Navy but also in the eleven state navies and privateer forces as well. Local black watermen from the Chesapeake Bay area were so valued as pilots for American ships that George Washington offered warrants of as much as $100 to these men. In several cases, blacks working for privateers received generous land grants for their service. Still others received pensions for service in the Continental Navy. For most, however, the most valuable compensation was freedom. Even the Virginia state legislature passed an ordinance that freed all slaves who served in their master’s place in the Virginia State Navy.3

Despite their contributions to the cause of American independence, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert decided to ban “negroes and mulatoes” from the service in 1798.4 The reasons behind this decision are still unclear. Stoddert, the son of a Maryland tobacco farmer, may have viewed blacks as inferior beings.5 Stoddert’s fear that the French Navy might export the recent slave revolt in Haiti to the American south may also have played a role.6 According to historian Michael Palmer, the prevention of an invasion from the Caribbean “became the first task of the United States Navy,” and as a consequence, Stoddert may not have wanted to man his ships with crewmen who might show sympathy toward the ex-slaves of Haiti.7

The manpower demands of the Quasi War with France caused some of Stoddert’s captains to disregard this directive and recruit blacks anyway. During the War of 1812, the Navy officially ended its ban on African American recruitment, and by the end of the conflict, blacks represented 15 to 20 percent of the enlisted force. Black sailors manned guns, served in boarding parties, and took part in forays ashore. They also cooked, cleaned, caulked, and handled the sails. During the age of sail, the sea provided blacks with an alternative to slavery because the Navy, with its harsh discipline, dangerous work aloft, long periods at sea, low pay, and bad food, was so unattractive that the service had to accept any stable, sober volunteer, whatever his skin color. Still, some officers protested about recruiting blacks. In an 1813 letter to Commodore Isaac Chauncey, Master Commandant Oliver H. Perry, the hero of the Navy’s Lake Erie campaign, complained that some of the men sent to him were a “motley set, blacks, Soldiers and boys, I cannot think you saw them after they were selected—I am however pleased to see any thing in the shape of a man.” Chauncey, in response to this prejudiced note, wrote, “I have yet to learn that the Color of the skin, or cut and trimmings of the coat, can affect a man’s qualifications or usefulness.”8

Despite the strides made by black sailors during the War of 1812, the political situation between the northern and southern states led the Department of the Navy to impose quotas on black recruits during much of the early nineteenth century. To appease powerful, pro-slavery southern politicians like John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, Secretary of the Navy Abel P. Upshur promised in 1842 that African Americans would make up no more than “one-twentieth part of the crew of any vessel.” This quota succeeded in reducing the percentage of blacks in the Navy to 4.2 percent by 1850.9

The situation changed dramatically once the Civil War began in 1861. While blacks could not serve in the Union Army until 1862, they could serve in the Navy throughout the conflict, albeit at lower wages. Overall, blacks represented 10 to 24 percent of the warship crews, depending on time and place, during the Civil War. The proportion rose even higher on service craft and sailing vessels. Most served as cooks and stewards, but a small number became captains of the hold, captains of the foretop, carpenter’s mates, coxswains, and even gunner’s mates and quartermasters.10

As early as 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles authorized the recruitment of escaped or liberated slaves in the Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The Navy found escaped slaves easy to assimilate, and the racial policies on ships of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron had no impact on Union loyalists in Kentucky or Missouri who owned slaves.11 Initially, these “contrabands” could only serve as apprentice sailors or “boys,” but by 1862, they could enlist as landsmen (adults with no maritime experience). Landsmen received twelve dollars a month, about four dollars less than ordinary seamen, and “boys,” eight to ten dollars a month. The recruitment of former slaves significantly increased the numbers of blacks serving in the Navy during the Civil War. As of 2007, researchers have identified 20,000 Union black sailors from this war.12

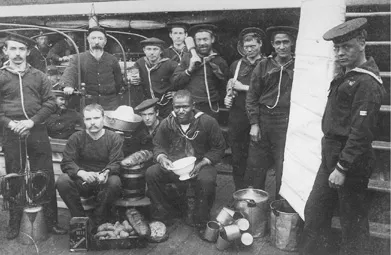

“Berth Deck Cook’s” in 1887 on board the USS Ossipee, a 1,240-ton steam screw sloop. During this period, blacks mainly served as cooks, stewards, and landsmen. (E. H. Hart)

After the Civil War, the percentage of African Americans in the Navy dropped from a wartime high of more than 20 percent to 13.1 percent in 1870, as segregation began to take hold in the United States. In the “Jim Crow” Navy, blacks mainly served as cooks, stewards, and landsmen, but some also worked as firemen, storekeepers, carpenters, water tenders, oilers, and in other specialized billets, and they messed and berthed with their white shipmates. A few even rose to the rank of third class petty officer.13

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision by the Supreme Court legitimized segregation in the United States and ushered in the beginning of a new era for blacks in the Navy. Beginning in 1905, the Navy began creating separate messes for these sailors, and recruitment decreased. By World War I, blacks constituted less than 3 percent of enlisted men, and almost all served in the galleys or engineering spaces. The Navy stopped enlisting blacks altogether in 1919 because officers thought Filipinos made better messmen. Commander (later rear admiral) Robert R. M. Emmett, the head of enlisted training in 1932, explained the nature of this bias in a letter to the Bureau of Navigation director of training, arguing that Filipinos “are cleaner, more efficient, and eat much less than negroes.”14 When Germany invaded France in 1940, only 4,007 African Americans served in the Navy, most as mess attendants, officers’ cooks, and stewards.15 It would take the Navy more than thirty years to erase this negative image of the sea service as a place where blacks were excluded from all occupations except that of domestic servants.

The prominent role white sailors played in the race riots of the summer of 1919 also tarnished the image of the service in the eyes of the nation’s African American community. In Charleston, South Carolina, an altercation between a black man and two white sailors in May 1919 ended with the black man being shot and killed. Shortly afterward, a series of running skirmishes erupted between sailors and members of the local black community. Eventually, Marines and police managed to quell the riot and compel the hundreds of sailors involved to return to the Charleston Navy Yard, but not before white sailors managed to inflict extensive property damage on black-owned stores.16

In Washington, D.C., an even more ugly confrontation occurred. Shortly after 10:00 P.M. on 18 July, a young white woman was jostled by two black men on Twelfth Street in the southwest quadrant of the city. The woman screamed and the men fled. The next day, the Washington Post and Washington Evening Star carried sensationalized accounts of the episode, claiming that this “wife of a naval aviator” was “attacked” by black men.17 The next day, a group of several hundred white sailors, soldiers, and Marines set out for the predominantly black section of the city near the Washington Navy Yard intent on lynching the suspects involved in the incident. This mob beat two black citizens with clubs and lead pipes and injured several more. On the 20th, a white mob beat two blacks in front of the White House. Shortly thereafter, soldiers attacked a group of blacks near the American League Baseball Park. On Monday, 21 July, four black men in a speeding car fired eight shots at a white sentry and several patients at the naval hospital in Georgetown.18 Another black man stabbed a white Marine near the White House, and a black woman shot and killed a white detective who had entered her home to investigate a shooting in the area. That night, a group of black men and women in a car sped through the streets of Washington, firing at various white pedestrians. This group wounded a policeman, a soldier, and several others before police managed to stop the car and kill the driver. On Tuesday, a mob of 2,000 whites attempted to attack a black section of the city but were dispersed by mounted troops aided by a heavy downpour of rain. More than 800 Federal troops and numerous police finally quelled the disturbance on the 23d. In all, six people lost their lives in the incident, and more than 70 others were injured. It was the worst riot in Washington to date, and the first 1919 riot to receive national attention by the press.19

By the end of the summer, rioting had spread to more than twenty-five American cities. In Chicago, 23 blacks and 15 whites died, and more than 290 people of both races were wounded in a conflagration on 27 July, which began as a stone-throwing fight between black and white youths at a local whites-only beach. During the unrest that followed, white sailors stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center participated in the beating and killing of black citizens caught in the downtown “Loop” area of the city. Significantly, the role of white sailors in the riot received much publicity in the Chicago Defender, one of the most widely read black papers in the country.20

As in Charleston and Washington, the causes of unrest in Chicago were complex. Massive troop demobilizations, competition for jobs between whites and blacks, urban overcrowding, and a local media prone to sensationalism were major reasons. However, it is significant for this book that white sailors helped provoke the riots and that all three events occurred near major naval shore facilities: the Navy connection to the riots of 1919 left an indelible impression on African Americans.

Relations between the “white” Navy and the black community improved little during the course of years leading to World War II. In 1932, blacks constituted just over one-half of 1 percent of the enlisted force (441 out of a force of 81,120), and 1 out of every 4 blacks in the Navy served as messmen.21 One year later, the Navy again opened the steward branch to blacks, but blacks did not begin to enter the Navy in significant numbers until after America’s entry into World War II. Illustrating the complete absurdity of these policies was a black mess attendant named Doris Miller. During the attack on Pearl Harbor, Miller was collecting laundry when he heard the call for general quarters. He headed for his battle station, the antiaircraft battery magazine amid-ship, only to discover that torpedo damage had wrecked it, so he went on deck, where he was assigned to carry the wounded to places of greater safety. An officer then ordered him to the bridge to aid the mortally wounded captain of the ship. He subsequently manned an antiaircraft machine gun until he ran out of ammunition and was ordered to abandon ship. For his heroism, the Navy awarded Miller the Navy Cross, the nation’s second-highest award for gallantry.22 Miller’s deed proved that blacks were just as capable as whites in performing all the duties required of a sailor.

The manpower demands created by that war necessitated a change in racial policies, but the Navy initially resisted the pressures. In March 1942, President Roosevelt finally ordered Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to begin accepting more blacks; Knox responded by enlisting more blacks for general service, but only in segregated units. By 1945, some 166,915 blacks were serving in the Navy (5.5 percent of the total enlisted force). Half of these men still served as cooks and stewards, and a third, as unrated seamen in black labor and base companies. Only 64 blacks received an officer’s or warrant officer’s commission—.02 percent of the total Navy officer corps.23 Among the first African Americans to receive officer commissions were the “Golden Thirteen.”24 In January 1944, the Navy selected a group of 16 black sailors to attend the V-12 officer training program, a college commissioning program similar in some respects to the modern Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) system.25 Of this number, 12 graduated with commissions and 1 became a warrant officer, apparently because he lacked a college education. The subject became a cover story in Life magazine and inspired many African Americans throughout the nation, but it did not end segregat...