![]()

PART I

A Promenade for the Bronx

![]()

1

“A Drive of Extraordinary Delightfulness”

IN THE LAST HALF of the nineteenth century, the sparsely populated acres blanketing southern Westchester County—the territory that would one day be known as the Bronx—might have struck most New Yorkers as the dullest place on earth; the action in those years occurred largely in Manhattan. But to a quartet of young municipal engineers who spent their workdays mapping the Town of Morrisania in the early 1870s, at least one portion of this area was rich with attractions: the expanse called Bathgate Woods that was thick with old-growth forest and vegetation. Bathgate Woods, later known as Crotona Park, was among the few remaining tracts of local wilderness and was so beautiful that in 1883 a city official described its trees as the prettiest of any south of the Adirondack Mountains.

During the week, the four civil servants busied themselves with compass and tripod, trying to impose order on the crazy-quilt street system north of the Harlem River. Their weekends, however, were their own, a time when these youths, barely out of their teens, could release some high spirits in one of the undeveloped tracts of land that were fast disappearing from the scene.

Bird’s-eye views of geographical features flourished in the middle and late nineteenth century—one of the most famous images of the Grand Concourse is presented in such a fashion—and a bird’s-eye view of what eventually became the Bronx would have depicted an area with two very different personalities. The irregularly shaped forty-two-square-mile expanse—the only portion of what would become New York City that was attached to the mainland—was bordered on the west by the Hudson and Harlem rivers and on the east by the East River and Long Island Sound. The portion to the east of the Bronx River was largely flat and in some places marshy, whereas the section to the west was so hilly that when streets were built, many had to be equipped with steps to march them up the steep slopes. The most noticeable features of the terrain were three massive wooded ridges that ran from north to south; the westernmost ridge overlooked the Hudson and Harlem rivers and the New Jersey Palisades; the easternmost ridge passed through Bathgate Woods.

Bathgate Woods was the destination of the four adventurers. Every Saturday afternoon during the hunting season, they met at their office at 138th Street and Third Avenue, then headed north aboard the Huckleberry Horse-car, so named because its leisurely pace gave passengers a chance to scramble off and pick berries along the way. At the final stop, they shouldered their rifles and trudged up the hill to an old stone hunting lodge perched near the crest of the ridge. The innkeeper was an aging Frenchman, and his manners and accent would have offered a welcome touch of home to one of the four visitors, a young man named Louis Risse who had come to America just a few years earlier from a small village in Alsace-Lorraine.

At four the next morning, the quartet set off in search of the grouse, pheasant, and quail that roamed the massive central ridge. Through acreage punctuated by jagged cliffs and gashed by rugged valleys, they ranged north to what was to become Van Cortlandt Park and the Westchester County line. From there, they headed south to what was left of the Morris estate, the once vast holdings of the family of the long-dead Lewis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Even for energetic young men used to tramping the woods as part of their jobs, the terrain must have posed a challenge. But to Risse, the newly transplanted Frenchman, those rocky expanses also offered the inspiration of a lifetime. The crisp autumn days, and in particular that great ridge, lingered in his mind. Perhaps it appeared in his dreams; it certainly haunted his waking hours. Two decades later, that ridge inspired him to create a brilliantly designed street—a Grand Boulevard and Concourse, he called it—that ran almost the entire length of the borough that was his home, profoundly shaped its development, and exerted a powerful ripple effect that extended far beyond its borders. In 1902, a moment when the project was mired in political infighting and still seven years away from completion, Risse published a brief but moving account of its conception that opened with a vivid description of those excursions in the woods.

The part of the city where those weekend expeditions took place had changed a great deal since the first European settler, a Swede named Jonas Bronck, had arrived in 1639 and two years later purchased five hundred acres of American soil east of the Harlem River. From Colonial days on, the territory had been part of Westchester County, and by the mid-nineteenth century, the landscape was dotted with farms that produced fruits, vegetables, meat, and dairy products, along with country estates, market villages, and fledgling commuter towns—all signs of New York City’s relentless push uptown. Epidemics of cholera and yellow fever also helped drive population north; these ailments were often vaguely attributed to “bad air,” and bracing country breezes seemed the ideal antidote.

Surveyors at work in the Annexed District, also known as the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Wards. That part of southern Westchester County eventually became the West Bronx. (The Great North Side)

The first villages had arrived hard upon the construction in 1841 of the New York and Harlem River Railroad. Wherever a station was built, there a community sprouted: Melrose, Mott Haven, Fordham, Tremont. The earliest settlers of Morrisania, for example, were skilled workmen from the Bowery who in 1848 followed the rail line north, partly to be within commuting distance of their jobs in Manhattan and partly in search of an environment where their children could grow up close to nature. Within a decade after their arrival, Morrisania boasted a hodgepodge of one-family and two-family wooden houses along with a blacksmith and a few shops, the spire of St. Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church providing the only hint of skyline. The oldest known photograph of the Bronx, an 1856 image of the village of Tremont—a community that sat along the route the Cross Bronx Expressway would follow a century later—shows barns, stables, houses, taverns, and a sprinkling of other local businesses, with cultivated fields in the distance.

Other settlements were far more sumptuous. As summering outside the city became an increasingly chic practice, well-heeled New Yorkers built lavish estates on these undeveloped acres and erected imposing villas, many of them generously gabled affairs topped by chimneys and ringed with porches. Some families journeyed to their estates entirely by carriage, driving north along Central Avenue, the favorite route to the fashionable Jerome Park racetrack and a thoroughfare that eventually took the racetrack’s name.

By 1860, only about seventeen thousand people lived in the area. But the year 1874 brought a watershed event, the annexation to New York of a huge swath of southern Westchester County—the towns of Kingsbridge, West Farms, and Morrisania. On the stroke of midnight, nearly a score of villages dotting a twenty-square-mile area—everything south of Yonkers and west of the Bronx River—were incorporated into the city. Some twenty-eight thousand new New Yorkers were created in an instant.

The acquisition of the so-called Annexed District—the western half of what is now the borough of the Bronx—marked the first expansion of the city outside Manhattan. The newly acquired land also provided a canvas on which the young civil servant from Alsace-Lorraine left his remarkable legacy.

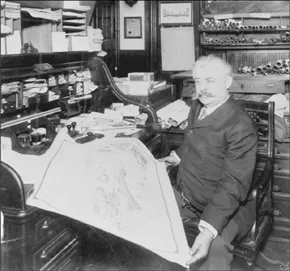

Louis Aloys Risse entered the world in March 1850 in the town of St. Avold, near the German border. Family legend had it that he came from impressive stock, and in an account of his birth written nearly half a century later, he described his mother’s family as notable for “conspicuous ancestry.” His maternal grandfather had been a decorated officer in Napoleon’s army, and he himself was born in a former castle that was once home to a duke.

Though nudged toward a career in the priesthood, Risse quickly rejected the idea. Instead, he headed for Paris, where he studied drawing and painting, and at the age of seventeen, he sailed for America, envisioning the visit as the first stop on a round-the-world journey. But he got no farther than the country acres north of Manhattan. Risse apparently fell in love with the place, so much so that he decided to make his permanent home there and pursue a career as a civil engineer. He remained in the Bronx for the rest of his life, the last thirty-six years in a mansion on what was known as Mott Avenue, a street that would be incorporated into the Grand Concourse around the time of his death.

Louis Risse, the visionary engineer who designed the Grand Concourse, in his office in the late 1800s. Though some people dismissed him as “the crazy Frenchman,” the boulevard he created came to rank as one of the premier streets in his adopted country. (Museum of the City of New York)

Risse could not speak a word of English when he arrived in the United States in 1868. Yet thanks to his professional training and his own capabilities, he quickly landed one engineering job after another, each more prestigious than the last. After working briefly as a railroad surveyor, he completed a street map of the town of Morrisania and helped draft a survey map of what became the Annexed District, officially known as the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Wards. There followed a series of municipal posts: assistant engineer in the Park Department, superintendent of roads in the Annexed District, and, in 1891, chief engineer in the district’s Department of Street Improvements.

Risse’s old hunting ground, the terrain he knew so intimately, ran like a golden thread through those years. At the Park Department, he personally surveyed the territory. As superintendent of the Annexed District, he was responsible for maintaining existing roads and charting the route of new ones. Over nearly three decades, he devoted himself to the taming and ordering of these acres, a task he mastered with growing proficiency.

Risse’s career progressed so smoothly and speedily, it is impossible not to speculate on the qualities that helped a lowly civil servant with a polished continental manner but no apparent political connections rise so fast and accomplish so much. Certainly he was smart, ambitious, and energetic, an immigrant who eventually ascended to the post of chief map-maker of the newly consolidated metropolis. A brief biographical sketch written during the height of his career describes him as “hale, hearty . . . of fine and pleasing presence . . . gentle, suave of manner.” Such encomiums were typical of the age, but in Risse’s case, they have the ring of truth. The subject of these generous words must also have been something of a poet; although some people dismissed him as “the crazy Frenchman,” his writings are informed by an almost lyrical sense of what his adopted city might one day become.

In his vision of the New York of the future, particularly the arteries that would link its disparate parts, Risse focused not simply on getting from here to there but, more important, on the agreeableness of the journey—the ease, the charm, the logic. Like the best urban thinkers, he possessed a sweeping imagination and seemed able to visualize, often with almost prophetic accuracy, the face of the future. His was hardly a city for everyman; the New Yorkers on whose needs Risse focused were not the huddled masses but elegant boulevardiers who could have stepped out of a Manet painting. Nevertheless, many of the values embodied in his work had a high social and even moral purpose. And in an era in which the vast majority of the population lived pinched lives in cramped and dreary quarters, Risse believed passionately in the importance of creating beautiful open spaces and crafting efficient and attractive ways of traveling to and from them, even if a fine carriage was needed to make the journey.

At the moment that the first glimmerings of what would one day be the Grand Concourse entered Risse’s mind, development north of the Harlem River was proceeding haphazardly and, in his considered opinion, quite stupidly. The Annexed District fell under the jurisdiction of what was officially known as the city’s Department of Public Parks, and due largely to the political paralysis that resulted from a mayoral administration that changed hands every two years, the district seemed fated to sit unimproved for some time. Perceived as suburban rather than urban, the terrain struck many people as more suited to a parklike system of streets than a crisp, city-style layout. In addition, New Yorkers increasingly regarded the Bronx as Manhattan’s playground, a recreation area to serve a crowded island whose population was growing by 6 percent every year.

Between 1884 and 1888, the city spent upward of nine million dollars to acquire nearly four thousand acres of raw parkland, most of it in the northern Bronx. A few years later, King’s Handbook of New York City reported that the great expanses of green in the North Bronx—among them Van Cortlandt Park, Pelham Bay Park, and Bronx Park, future home of both the New York Botanical Garden, founded in 1895, and the New York Zoological Society, which opened its doors in 1899—had become immensely popular among people able to make their way to them. These tracts were, the guidebook reported, “already frequented by those who wish a rustic outing in the wild woods and pastures,” used for picnics in summer and skating parties in winter. Yet visitors were few. Despite the enormous outlay of money for open space, no one had bothered to create a system of roadways linking the greenswards of the Bronx to the populated portions of Manhattan, and those who ventured north reached their destination only after a long and muddy journey. Thanks to municipal indifference, these lush areas sat in splendid isolation, far distant from the city’s heart.

Toiling in and out of government during those years, Risse fretted quietly about this state of affairs, but a single individual, even a talented and hardworking public servant, was hardly in a position to rectify the situation. Many of his fellow Bronxites were not so patient. Increasingly fed up with the government’s apparent inattention to local development, they began agitating for action, making their case so noisily and so persuasively that the state legislature finally stepped in to investigate the whole mess. A Department of Street Improvements for the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Wards was set up, and in 1890, Louis J. Heintz was elected as the agency’s first commissioner.

The young scion of a wealthy family, Heintz arrived at the job with no previous experience in government. Born in 1861, he started out in his uncle’s brewery, married the daughter of a millionaire brewer, then chucked the beer business for a career in public service. He held the commissioner’s job for only two years—he died in March 1893 from pneumonia contracted during a trip to Washington to attend President Cleveland’s second inauguration. Nevertheless, during his brief time in municipal government, Heintz made one prescient decision that transformed the face of the borough: he appointed Risse as his chief engineer.

It was a daunting assignment. Although the few roads that existed in the district were almost indescribably awful, the building of replacements had emerged as one of the most politically fraught issues of the day. In testimony before the state legislature in Albany, a prominent Bronx attorney and reformer named Matthew P. Breen painted a grim picture of the byways of the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Wards, describing them as “elongated mud ponds, punctured here and there with turbid pools of stagnant water and malodorous filth, the ever present parent of disease and death.” As for the political shenanigans that accompanied the building of new roads, “A man might go to bed one night with a street apparently established in front of his house, and before he retired to rest the next night the plan would be changed, and he might find the street located in the back of his house.”

Local pressure for development was not the only force helping to shape the Annexed District during those years....