![]()

1

Understanding Men on Television

There is no easy starting place for assessing men and masculinity on US television at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The past of this object of analysis is too expansive for simple summary and the limited existing research is too brief and haphazard to build a comprehensive picture of even general typologies from secondary sources. Although men were the central characters and figures in both fictional and news programming for much of the medium’s history, it was not until gender issues became a central part of social deliberations and the roles of men began adjusting in response to various “new women” in the 1970s that much attention was paid to men as “men on television.”

This study is delimited in a number of ways that require clarification and explanation, as the construction of topical and thematic boundaries and choices of exclusion are deliberate and always meaningful. The first delimitation is one of chronology, described most simply here as the beginning of the twenty-first century. As the following discussion explores, that era was characterized primarily by the emergence of television storytelling that began—technically in the late 1990s—to offer up conflicted and complicated male protagonists struggling in some way with the issue of how to be a man at this time. But two related concepts require further explanation beyond the chronological distinction of the twenty-first century. These series were part of a specific cultural milieu, but as I make clear, it is sociocultural events that began some thirty years prior that provide the particularly salient aspects of this milieu and require the extended explanation of “post-second-wave” as a descriptor of the sociocultural context most relevant here. The industrial context of US television in the twenty-first century is also crucial to grounding the institutional dynamics specific to cable relative to the long history of broadcast television at this particular time.

Another delimitation involves explaining the key theoretical terms and understandings guiding my analysis. Dismantling the binary opposition of feminine and masculine in order to create a language that speaks of various masculinities has been one of the great advances of gender theory in the last quarter-century. The somewhat endless possible modifiers for masculinities that result, however, require exceptional deliberation and precision in establishing key terms, especially when many lack shared use. My insistence upon speaking of “hegemonic masculinity” as specific to each series rather than consistent across texts or within US culture requires explanation, which is offered amidst a brief summary of the theoretical tradition of hegemonic masculinity in gender studies and media scholarship. I also locate my critical foundations and enumerate other key vocabulary in this subsection. I do use the term “patriarchal masculinities” in the first subsection; for now, this term should be understood as referring to behaviors or attributes that reinforce men’s dominant gender status in the culture.

Finally, I briefly establish the relevant television storytelling context for the series discussed here through an exploration of the aspects of television masculinity most common in the era immediately preceding this study. Scholarship about men and masculinity on television from the 1980s through the 2000s frequently attended to a gender construct termed the “new man” that arguably represented a preliminary phase of post-second-wave negotiation of masculinity on television. Many of the men and their struggles with masculinity examined in this book extend the project of the new man’s challenge to patriarchal norms by illustrating a next stage of negotiation between patriarchy and feminism in the construction of culturally sanctioned masculinities. The male characters of the 1980s and 1990s bore the imprint of a patriarchal culture in the initial throes of incorporating feminism into its structuring cultural ideology, while the series and masculinities considered here indicate more extensive—although far from complete—effects of feminism.

The expanded influence of feminism can be seen most notably in the differences between what the narratives blame for men’s struggles in different historical contexts. Though some may presume that the depiction of contentious lives and identity crises for straight white men illustrates a response to lost privilege and an endeavor to reclaim it, the analysis that follows indicates a far more complicated construction of the causes of these men’s problems.1 Although the protagonists in the male-centered serial appear perpetually flummoxed about how to be “men” in contemporary society, they do not blame, contest, or indict the feminist endeavors that created the changes in norms that lead to their uncertainty. In moments when frustration and anger with their circumstances become explicit, they most commonly blame their fathers—those who embody patriarchy—for leaving an unsustainable legacy. Like the new men who preceded them, the male characters considered here embody masculinities increasingly influenced by feminist ideals regardless of whether they are protagonists in the male-centered serials, those shown interacting in homosocial enclaves, or those depicted sharing intimate heterosexual friendships. The consistency with which the series show characters struggling over particular aspects of masculinity—as well as the aspects of patriarchal masculinities not indicted or struggled over—informs assessments of the state of cultural discourses that construct socially preferred masculinities at this time.

Why the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century?

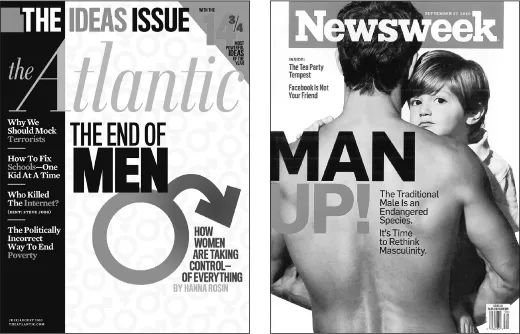

The negotiation of emergent masculinities apparent in cable drama in the early 2000s cannot be clearly traced to a single cause but can be linked to a confluence of industrial, sociocultural, and textual forces explored below. Perplexingly, it is not the case that something in particular happens at the transition to the twenty-first century—there is no catalytic moment or event—but rather, gradual adjustments in all of these areas over the preceding decades contribute to creating a context in the early twenty-first century in which contestation of aspects of patriarchal masculinity and uncertainty about culturally preferred masculinities occurs. Journalists increasingly attended to evidence of shifting gender norms in US society throughout the early 2000s so that the depiction of fictional characters considered here existed alongside sometimes anxious discourse about men and male gender roles on the covers of popular books and newsstand fare. The Atlantic’s Hanna Rosin claimed the “End of Men” in a widely discussed cover story that she expanded into a like-titled book published in September 2012, while a Newsweek cover story, a book, a television show, and an advertising campaign featured titles demanding that American men “Man Up.”2 Though much of this attention could be dismissed as merely the latest instance of the perennial concern about men’s roles that emerges whenever some deviation from patriarchal masculinities arises and that is often described as evidence of “men in crisis,” there were also hints of sociocultural changes in men’s roles that suggested something more than a superficial phenomenon at stake.

Figures 1.1 and 1.2. Popular journalism addressing and constructing anxiety about mid-2000s masculinities.

Speculation on gender crisis often exists as a pendulum within popular culture, swinging back and forth with considerable regularity, and, as these cases suggest, the focus was on men in the early twenty-first century. Even public intellectuals such as esteemed gender historian Michael Kimmel explored the consequences of pressure to be a “guy” in Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, while Leonard Sax, who studies gender differences in the brain, published Boys Adrift, both in 2009.3 Each offers a social-scientific perspective—of a sociologist and psychiatrist, respectively—on concerns about the situation among young, mostly white, and otherwise privileged men in books aimed at a popular audience. Their framing of the situation in terms of “panic” seemed meant to incite the moral concern optimal for book sales, and each attends most superficially to media while neither considers television at all. In Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys, Kay Hymowitz explores the phenomenon of the Millennial generation extending adolescence through their twenties, though despite the title, it seems more a distinctly classed generational phenomenon than a gender crisis.4 Sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s more recent study of the rise of single living in Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone explores the changing life patterns and living arrangements of young and older Americans without the alarmist agenda and offers much more extensive context for the phenomenon Kimmel and Hymowitz identify.5

Rather than relying on casual evidence of a new male crisis characteristic of journalistic and “academic-lite” assessments of changing gender scripts, I locate the origins of the complicated negotiations of masculinities and manhood in the series considered here in second-wave feminism and its outcomes. I very deliberately do not use the frame of “postfeminism”—a term I now find too fraught with contradictory meanings to be useful—and also dismiss the assertion that these gender relations are characteristic of “third-wave feminism.”6 The challenge to patriarchal masculinities evident in many aspects of the series is more clearly an outcome of second-wave activism—albeit long in fruition—than a result of more nascent feminist generations or their endeavors, which makes “post-second-wave” my preferred terminology.

Why “Post-Second-Wave” Masculinities?

Changes in gender relations occurring in the late twentieth century—particularly those related to securing equal opportunity of access to public realms such as education and employment—are typically considered as an outcome of feminism and as gains in the rights of women. However, the changed social and cultural spheres wrought by second-wave feminism have had enormous, if under-considered, implications for men as well. Too often, simplistic journalistic assessments of gender politics—particularly those of conservative punditry—suggest that the gains feminism has delivered for women correlate with lost rights or freedoms for men.7 But social justice is hardly a zero-sum condition, and the revised gender scripts that have been produced by second-wave feminism, the gay rights movement, and related adjustments in cultural norms—such as economic shifts eliminating the “family wage” for men and necessitating two-income households to achieve middle-class status—have introduced complicated changes in the gender scripts available to men as well. Understanding why particular masculinities emerge in early 2000s cable series—some of which openly contest many aspects of patriarchal masculinities—requires assessing these series in relation to the sociopolitical changes of the last twenty-five to thirty-five years. I identify this time span as “post-second-wave” for a variety of reasons, but acknowledge some apprehension about this identifier.8

As it is used here, “post-second-wave” encompasses both the explicit activist endeavors that began affording women greater rights and the way that activism became constitutive of the social milieu that acculturated American men and women born after the late 1960s. It is not strictly a chronological marker, intended to suggest “a time after” the era of midcentury feminist activism known as the “second wave” in the United States, a period commonly identified as roughly the late 1960s through the 1982 failure of the Equal Rights Amendment. Rather, I use “post-second-wave” as a more conceptual designation to acknowledge the accomplishments of second-wave feminism in significantly adjusting dominant ideology and gender scripts. Indeed, much evidence of activist gains required a quarter of a century to come to fruition and appeared only after a period of retrenchment widely referred to as “backlash”: a term Susan Faludi used to identify a prevalent theme in popular media in the 1980s and early 1990s through which women’s problems were consistently presented as created by second-wave feminism’s efforts toward women’s liberation.9

The contestation of patriarchal masculinities I consider owes far more to the activist work and consciousness raising begun during second-wave feminism than to anything else. Policy changes providing greater equality of opportunity for women in the workforce may have been enacted in the 1970s, but the wide-ranging and deep adjustments in cultural formations and gender scripts that they enabled required significant time to manifest. The benefits of these adjustments were first substantially enjoyed by women, who—like me—were children at that time, and who, along with male peers, grew up with contested gender politics but also a nascent gender order fundamentally different from that of our mothers and fathers. Consequently, it requires decades to really observe the social transformation of professional ranks and corresponding shifts in families and dominant social scripts for women and men, and similarly as long to observe changes in cultural forms.10

To be clear, in acknowledging the success of second-wave feminism, I do not mean to suggest that it ended patriarchy or that feminism’s work is now done. Much evidence makes clear that Western societies remain characterized by patriarchal dominance, but it is also evident that the work of second-wave feminists notably and significantly changed these societies, in particular, by opening many public spaces to women and adjusting prevailing notions of their roles. Though using the modifier “post-second-wave” to distinguish the emergent masculinities explored here may suggest more exclusively causal importance of the second-wave women’s movement than I really intend, no other term offers more precise identification, and the explicit link to feminism is significant to the perspective of the project.11

Gender scholars or cultural historians have yet to name or identify a shared term for describing gender politics and relations after the period of “backlash,” yet an important transition in the central fault lines of gender politics and dominant cultural debates occurred near the end of the century. The nexus of increased attention to international policy in the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks and the subsequent “Great Recession” shifted the US political focus and inadvertently revised the representational context of popular culture. This new era has been categorized, uncertainly, as “postracial” and “postfeminist”—both, unquestionably, complicated and disputed concepts, typically deployed without explanation of their intended connotation. Yet, their prevalence probably stems from the conceptual purchase they possess for acknowledging the notable difference between the issues central to American cultural debates in the 2000s and those of the preceding two decades.12 Discourses about the menace of “welfare moms” and the domestic destruction wrought by “working women” that were preponderant in cultural politics during the 1980s and early 1990s were replaced by a turn away from these cultural debates in the early twenty-first century to political questions of “weapons of mass destruction,” “enemy combatants,” and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The economic crisis delivered by an under-regulated banking industry, followed by a return to examination of and debate about economic policies ranging from health care to the unionization of government workers to all manner of deficit-cutting and austerity measures, monopolized the cultural agenda, bringing uncommon popular attention to class and wealth distribution—though notably, issues of gay rights and marriage persisted and even dominated the cultural agenda at times, particularly in the late 1990s through the early 2000s.

As some of the contentious cultural debates of the 1980s and 1990s moved out of focus, revisions in dominant ideology occurred and incorporated aspects of their contested feminist and antiracist politics. The cultural politics of the 1990s were dominated by a seemingly continuous debate over so-called political correctness that melded with interrogation of crises that intersected aspects of gender and race, including the Rodney King beating, police acquittal, and LA riots, Anita Hill’s charges of sexual harassment during Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court nomination, and Nicole Simpson’s murder and the subsequent trial and acquittal of O. J. Simpson. During the turn to world politics and economic policy following 2001, certain forms of multiculturalism that were openly contested in the deliberation over these news stories throughout the 1990s became increasingly hegemonic, as did women’s place in the workforce, the criminalization of domestic violence, and the inappropriateness of hostile workplaces.13 Other initiatives—such as those related to immigration policy—remained contested, while still others—such as accessibility to affordable childcare—fell off the sociopolitical agenda or were decreasingly perceived as feminist issues, as was the case with universal healthcare.

It remains the work of a cultural historian to flesh out this process of adjusting cultural norms and ideology with more nuance and to pose terminology that identifies this postbacklash era. The absence of such work leaves me with “post-second-wave”—a term not meant to exclusively signal cultural adjustments that can be linked to second-wave feminist activism but nevertheless a descriptor of the cultural milieu created in the aftermath of its most extensive policy endeavors. Indeed, because cultural change is complicated and slowly realized, a nexus of intersecting social developments, including the shift to post-Fordist economic practices and the rise of neoliberalism, simultaneously also shape the milieu in a way that makes it difficult to sustain assertions of a singular or particular cause. The cultural forces most salient to the negotiation of patriarchal masculinities I consider can be linked explicitly with femini...