![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

“A New Generation of Americans …”![]()

ONE

“Bastions of Our Defense”: Cold War University Administrators

Military-sponsored university research in the United States dramatically increased during World War II as the federal government attempted to achieve technological superiority over the Axis Powers. The advent and intensification of the Cold War, and the United States’ commitment to contain Communism, especially in the Third World, firmly joined together the university and the military. By the mid-1950s the Pentagon supplied $300 million annually for university defense research and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Johns Hopkins were placed on the list of the nation’s top one hundred military contractors. Thirty-two percent and 11 percent of federal research funds to universities in 1961 came, respectively, from the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The leading university military contractors in 1969 were MIT, the University of California system, Illinois, and Michigan, each receiving, respectively, $97 million, $15 million, $11.6 million, and $11.4 million in defense grants. The Pentagon underwrote 80 percent of MIT’s budget in 1969 while Michigan in 1967 held 64 separate contracts with the DoD totaling $11.8 million. Michigan in the 1960s also had more National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) contracts than any other university in America.1

Universities in 1968 spent $3 billion annually for research and development. Seventy percent of this money came from the federal government, of which over half originated from defense-related agencies. One of every three dollars spent on university research and development had either a military origin or purpose. The AEC, DoD, and NASA, respectively, in 1968 gave universities $110,200,000, $243,100,000 and $129,500,000 for military-related research. Over 30 percent of all academic research funds in the physical sciences in 1971 came from the DoD while the DoD and NASA provided 65 percent of all research support in academic engineering in the early 1960s.2

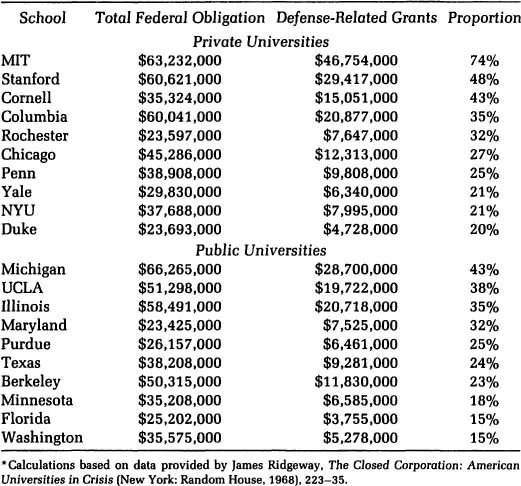

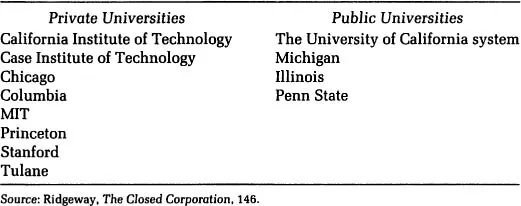

The significance of military contracting to the universities can be shown by calculating defense-related grants from the AEC, DoD, and NASA as a proportion of overall federal government obligations to institutions of higher education. (See Table 1.1.) In 1966, 43 percent and 35 percent of the federal grants given to Michigan and Illinois, respectively, were from defense-related agencies. Conversely, 25 percent and 21 percent of the federal grants given to the University of Pennsylvania and Yale, respectively, were from defense-related agencies. In terms of defense-related funds as a proportion of overall federal financial obligations to higher education, the most prominent public universities, by the 1960s, often relied just as heavily on such grants as the private universities. The public universities were sometimes more dependent on defense contracts than the private schools.3

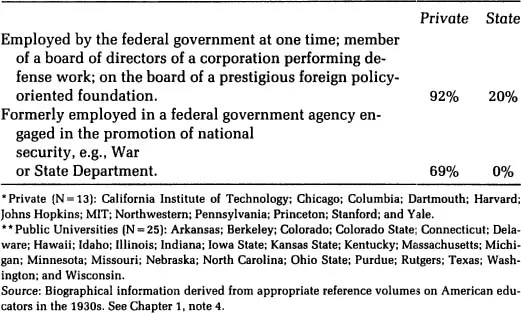

Private institutions of higher education, as opposed to the state universities, had been involved in promoting national security long before the advent of the Cold War. One way to illustrate this is to undertake a comparative study of thirteen presidents of private educational institutions and twenty-five randomly selected public university presidents in 1933. (See Table 1.2.) Ninety-two percent of elite university presidents had ties to the federal government and claimed membership on the boards of directors of influential foreign policy-oriented foundations or large corporations, many of which had substantial federal defense contracts. More important, 69 percent had rendered service to the federal government in the War and State Departments or in some agency concerned with national security. The entrance of the United States into World War I and the nation’s subsequent emergence as a world power had drawn academics from the elite private universities into governmental service. After World War I, such institutions and academics, notably MIT’s Vannevar Bush, remained involved in promoting national security.4

In contrast to the presidents of elite private schools, only 20 percent of state university presidents in 1933 claimed federal government service, primarily in agencies concerned with agriculture or education. None had been involved in the promotion of national security during or after World War I. And no public university president was a member of the board of directors of a major corporation performing defense work or of a foreign policy-oriented foundation.5

Table 1.1

Defense-Related Grants as a Proportion of Overall Federal Obligations to the Largest Private and Public University Military Contractors, 1966*

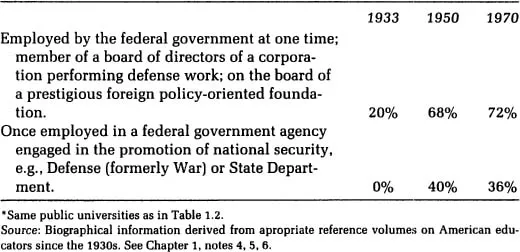

This situation changed decisively during and immediately after the Second World War. Sixty-eight percent of state university presidents by 1950 had served the federal government in some capacity. (See Table 1.3.) Forty percent had been employed in the Defense or State Departments during World War II. Robert Sproul of Berkeley and Frederick Hovde of Purdue had worked under Vannevar Bush in the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) during World War II. Hovde brought former OSRD scientists, as well as defense contracts, to Purdue upon becoming president in 1946. The president of Iowa State, Charles Frieley, acquired a piece of the Manhattan Project in 1942 for his school and, in 1947, an AEC research facility.6

Table 1.2

Comparative Profile of Private* and Public University** Presidents, 1933

Table 1.3

Comparison of Public University Presidents,* 1933, 1950, 1970

Table 1.4

Members of the IDA University Consortium

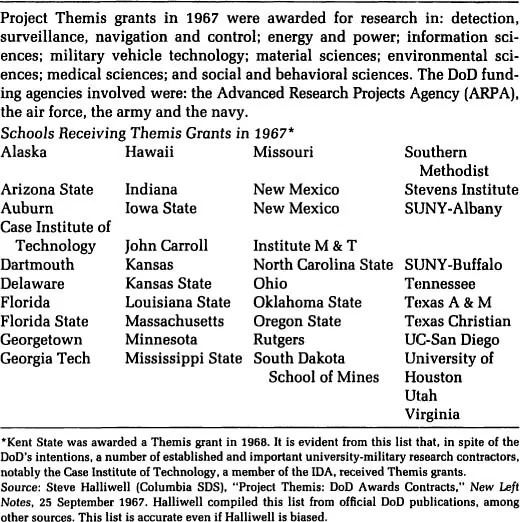

Administrators and faculty, with technical expertise in weapons development and foreign policy experience obtained in World War II, and with Ivy League pedigrees, flowed into the expanding state universities: Berkeley, Michigan, Michigan State, and Penn State, to name a few. By the end of the 1950s, the larger state universities had secured the requisite scientific personnel to be able to cooperate with elite private schools in defense research. This cooperation was formalized in 1959 by James Killian, Jr., chairman of the board of MIT, who put together the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), a private and state university consortium originally designed to evaluate weapons systems for the federal government. (See Table 1.4.) Smaller, less prestigious state universities, for instance, the University of Delaware and the University of Hawaii, did not amass the necessary scientific personnel and acquire significant defense contracts until the late 1960s when Defense Secretary McNamara announced the creation of Project Themis. According to the DoD in 1967, Themis was aimed at providing federal grants for military research to the “have-not schools.” (See Table 1.5.) Both Kent State and SUNY-Buffalo received Themis grants.7

Table 1.5

Project Themis, 1967

Elite and state universities differed not only in the timing of their penetration by the defense establishment, but also in the roles they played in promoting national security. Harvard and Yale in the twentieth century have generally served as national security managerial training and recruitment centers. Applied weapons research and technical assistance field operations in the Third World have not been the forte of elite universities. Since the advent of the Cold War, it has been the state universities which have received enormous federal grants for weapons research and development and have provided specialized personnel to staff technical assistance field operations around the world. Harvard and Yale graduates formulate national policy; Michigan State and Penn State graduates execute national policy.

Institutions of higher education received federal grants not only for support of defense-related research, but also to facilitate the universities’ physical plant expansion and to provide financial aid to students. There were at least three major motivating factors behind the federal government’s heightened commitment to higher education after World War II: first, the nuclear arms race and Communist revolutions in the Third World required highly educated engineers and foreign-area specialists to develop new weapons systems and counterinsurgency scenarios to advance national security; second, the nation’s rapid economic expansion and the desire for sustained prosperity meant that industry needed more, and better trained, technicians; and third, the postwar baby boom created an enlarged pool of potential college students. Middle-class parents viewed higher education as a means to upward social mobility and expected the federal government to ensure that their children would be able to go to college. For these reasons, the university faculty and student population advanced at a phenomenal rate. Between 1948 and 1957 the number of faculty increased from 196,000 to 250,000. By 1968, there were half a million university faculty in the United States. In 1955, 2,418,000 and 242,000 students were enrolled, respectively, in undergraduate and graduate programs. The number of students more than doubled ten years later and nearly tripled by 1970 with 6,481,000 undergraduate and 816,000 graduate students enrolled in institutions of higher education. Public four-year institutions claimed 1,072,980 students in 1960 and 2,914,000 in 1965, or 59 percent of all college students.8

Political conservatism characterized the administration of American universities in the years following World War II. In 1958, 102 of 165 colleges and universities surveyed reported political firings of activist faculty. The drive to discipline activist faculty, as well as students, in part emanated from the universities’ boards of trustees. In general, university trustees occupied executive positions in major corporations—companies which frequently performed defense-related contracting—and held conventionalist political beliefs. Twenty percent of all American university trustees in 1968 were on the boards of directors of leading corporations and 80 percent favored the expulsion or suspension of student activists.9

Clark Kerr, president of the University of California system, contended in 1963 that institutions of higher education had become “multiversities,” the focal points of “knowledge production,” promoting technological development in the private and public sectors:

The production, distribution, and consumption of “knowledge” in all its forms is said to account for 29 percent of GNP … and “knowledge production” is growing at about twice the rate of the rest of the economy. Knowledge has certainly never in history been so central to the conduct of an entire society. What the railroads did for the second half of the last century and the automobile for the first half of this century may be done for the second half of this century by the knowledge industry: that is, to serve as the focal point for national growth. And the university is at the centre of the knowledge process.10

Beyond its vital function as a producer of knowledge, the university was also, Michigan president Harlan Hatcher observed in 1959, a key element in performing the research necessary to ensure America’s economic and military superiority over the Soviet Union. No university president in the 1950s and 1960s would have publicly disagreed with Kerr’s and Hatcher’s conceptions of the role of higher education in American society. A few, such as Martin Meyerson of SUNY-Buffalo, had private reservations, at least regarding the role of the university in defense research. And some, like John Hannah of Michigan State, embraced the idea of the university as “knowledge factory” and anti-Communist bulwark with unshakable fervor.11

Michigan State University

Born in 1902 of conservative parents, pillars of the Grand Rapids, Michigan, farming community, John Hannah dedicated his life to public service. Hannah came to the Michigan Agricultural College (later renamed Michigan State University) in 1922 to study poultry science. For the next nineteen years, Hannah worked as an agricultural cooperative extension agent for the college until succeeding his father-in-law as president—a position he held from 1941 to 1969. Hannah became secretary to the Michigan Board of Agriculture in 1940. Since Michigan was a key center of agricultural production, and food would be vital to the coming American war effort, Hannah attracted the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt. Soon, other prominent national political figures, including Nelson Rockefeller and Senator Harry Truman, heard about the dedicated and efficient agricultural expert and college president from Michigan. In 1950, President Truman selected Hannah to be a member of the International Development Advisory Board which formulated policies for the Point Four program of American diplomatic, economic, military, and technical assistance to the Third World. President Dwight Eisenhower in 1953 chose Hannah to serve as assistant secretary of Defense for Manpower and Personnel and in 1957 made him chair of the newly created Civil Rights Commission. Hannah remained on the commission during the administrations of Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Upon his retirement as MSU president in 1969, Hannah joined the Nixon Administration, becoming director of the Agency for International Development (AID).12

As a liberal Republican educator, Hannah viewed mass, affordable, federally subsidized higher education as the best way to develop human potential and improve the quality of life for all hardworking citizens, regardless of race or creed. After leaving the Nixon Administration Hannah reaffirmed his conviction that

governments exist to provide the services and opportunities that make it possible for the largest number of people to develop the potential that God gave them so that they may make the maximum useful contribution to the society of which they are a part. This is the thinking that justified public education in the first place, that created public primary schools, secondary schools, colleges and universities. Political, social and economic systems change, but the basic role of education does not.13

To ensure that all people could attend college, Michigan State, unlike Michigan, maintained a virtually open admissions policy and endeavored to keep in-state student tuition at reasonable rates in order to attract lower-middle- and working-class youths. Envisioning a student population of 100,000 by 1970, Hannah undertook, in the early 1960s, the construction of the world’s largest on-campus residential housing complex. In the years spanning 1950 to 1965, the undergraduate population rose from 15,000 to 38,000 and the proportion of liberal arts and social science majors grew from 20 percent of the student body in 1960 to 54 percent in 1970. Finally, the number of faculty increased from 900 to 1,900 between 1950 and 1965. By 1964, MSU commanded the eleventh-largest full-time student enrollment in the United States. At the same time, federal government support of MSU expanded so that by 1966 it accounted for 69 percent of the university’s overall appropriations. Of the $22,369,000 in federal grants given to MSU in 1966, 18 percent came from AID to support the university’s overseas technical assistance programs while the AEC, DoD, and NASA accounted for 11 percent.14

In addition to providing the masses with affordable higher education, the university, according to Hannah, also served as part of democracy’s arsenal poised against the “menacing cloud of Communism,” which threatened “the values and virtues so precious to free people.” In an address to educators and military personnel in May 1955, Hannah proclaimed:

Our colleges and universities must be regarded as bastions of our defense, as essential to the perservation of our country and our way of life as supersonic bombers, nuclear powered submarines, and intercontinental ballistic missiles.15

Given Hannah’s ties to the military establishment, coupled with the fact that MSU was one of the original universities involved in Truman’s Point Four program, it was logical that Vice President Richard Nixon requested the university in the spring of 1955 to undertake a mammoth technical assistance program in South Vietnam. From May 1955 to June 1962, the MSU Advisory Group (MSUAG) employed over 1,000 people and received $25 million from the the Foreign Operations Administration (later renamed AID) in an effort to train Vietnamese administrators and security personnel, thus filling the vacuum at the top bureaucratic levels created by the departing French colonia...