![]()

1

Religious Identification in America

Religious identification is a personal cognitive attachment to a religious group or tradition and may also reveal an actual or potential tie to religious organizations. Cognitive commitments to religious groups are important for structuring marital ties, for establishing childrearing patterns, and for providing lifelong socialization on how religion might impact the family, social life, status attainment, and political engagements. A connection to a religious group, even if it is only a cognitive identification, provides a source of institutional support for beliefs and behaviors. Identifications are usually a product of prior religious participation, and they are strongly associated with religious participation in the groups with which people identify. Most people who participate in religious groups also donate tangible resources to them, both financial and voluntary. GSS data show that 72% of respondents who report a religious identification have given money to a religious congregation in the past year, and 82% of people with some religious identification attended a religious service in the past year. Cognitive identifications with religious groups are strongly linked to the mobilization of resources by religious organizations.

Because of the connection of shifts in religious identification to religious mobilization, they provide an important image of religious change. Changes in the proportion of Americans holding particular religious identifications are a function of several factors, including differential fertility across religious groups, cohort replacement through the dying off of older identifiers, immigration, and people switching their religious identifications. These changes occur both over time and across generations. Fertility, of course, will only reveal itself as a key factor structuring religious identification in subsequent generations. And fertility effects will be strongly influenced by religious intermarriage and religious switching. Immigration is a constant feature of the United States’ demography, and over time immigrants have come in successive waves of immigration from varied religious and ethnic backgrounds. Religious switching can vary over time and also across generations (Roof and McKinney 1987; Sherkat 2001b) but is most often a single occurrence in the early life course (Roof 1989; Sherkat 1991). This chapter examines trends in religious identification and how these vary across generations and ethnic groups.

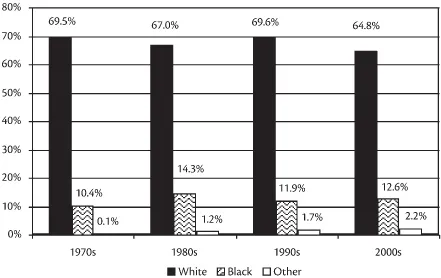

Over the past forty years, the ethnic composition of the United States has changed considerably through both fertility differentials and immigration. Ethnicity and immigration play a strong role in determining religious identifications, and changes in immigration policy after 1965 have changed the ethnic composition of different generations of Americans (Ebaugh 2003). Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show the ethnic and immigrant composition of the GSS samples by decade. Notably, data from the 1970s come only from 1977 and 1978 (the GSS was not conducted in 1979), when the question about immigration was added to the study. In the late 1970s, 69% of GSS respondents were native-born whites with both parents also born in the U.S. This total does not decline very much over time, but it does dip to 65% in the 2000s. The decrease in the proportion of nonimmigrant whites is offset by an increase in the proportion of African American and “other race” respondents. In the late 1970s, just over 10% of GSS respondents were nonimmigrant blacks, and only a tiny fraction (0.1%) of GSS respondents were nonimmigrants from other racial backgrounds. By the 2000s, the proportions of nonimmigrant African Americans inched up to almost 13%, while 2.2% of GSS respondents had two U.S.-born parents and claimed a race other than white or black.

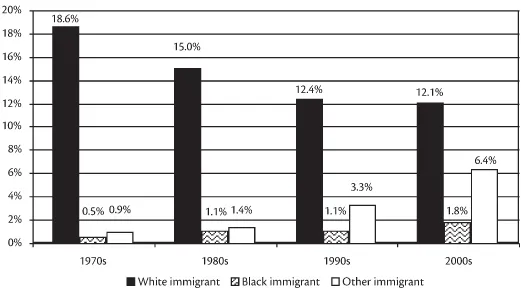

The shifting ethnic composition of the U.S. becomes even more pronounced when immigrants are examined. The proportion of Americans who have at least one parent born outside the United States has been fairly constant at about 20% of GSS respondents since the late 1970s; however, the race and ethnicity of immigrants has shifted considerably. Figure 1.2 shows that in the late 1970s, almost 19% of GSS respondents were white first- or second-generation immigrants, while in the 2000 surveys, just over 12% of respondents were white first- or second-generation immigrants. In the late 1970s, black and other race immigrants together only accounted for 1.4% of GSS respondents. Since 2000, the GSS samples have been 1.8% first- or second-generation black immigrant, and 6.4% first- or second-generation immigrants from other races. In the 1970s, GSS respondents were overwhelmingly white—69% native born and 19% white immigrants—88% of respondents were white. In more contemporary data since 2000, whites make up about 77% of respondents—12% of these being white immigrants. Nonwhites have gone from accounting for only 12% of the sample in the 1970s to making up 23% of GSS respondents. And in the 1970s, nonwhites were overwhelmingly native-born blacks—87% of nonwhite respondents. In the post-2000 surveys, only 55% of nonwhites were native-born blacks.

Fig. 1.1. Percentages of GSS respondents beyond the third generation in the U.S. by racial category and decade

Fig. 1.2. Percentages of GSS respondents who are first- or second-generation immigrants by race and decade (1977–2012 GSS)

Most treatments of American religion either ignore race and ethnicity or segment the experiences of African Americans and immigrants in a way that sidelines their importance. That strategy is a useful shortcut for dealing with the overwhelming diversity within American religion, particularly given the rapid assimilation of ethnic Europeans into Anglo-American culture and religion. But ignoring ethnic and racial diversity is not a viable strategy for understanding the future of religion in a changing nation. The assimilation of European ethnics into a homogenized set of Anglo-Christian denominations was a very unusual sociological occurrence (Hamilton and Form 2003), and that homogenization is not quite complete (as will be shown in analyses comparing western and eastern European Americans); and the American experiences of the new immigrant groups which have arrived since 1965 will likely proceed in a quite different fashion (Ebaugh 2003).

The Demography of Religious Change

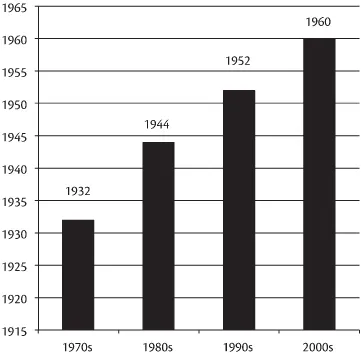

Normal demographic processes are the engine of much social change, and shifting religious commitments are no different. Every year, new Americans are born, die, or immigrate to the U.S. Migration out of the U.S. has not been a strong demographic influence on the structure of the U.S. population, though that could change in the future. If new generations and immigrants differ substantially from older generations, then eventually the character of the nation will appear more like the younger generations. Over time, older generations die off and are replaced by younger generations, what sociologists refer to as cohort replacement. Cohort replacement is what drives many of the dynamics of religious commitments. Figure 1.3 charts the median birth year of respondents to the GSS in the four decades examined. In the 1970s, the median GSS respondent was born in 1932. That means that half of the GSS respondents in the 1970s were born prior to 1933. In the surveys conducted since 2000, the median GSS respondent was born in 1960—meaning that half of the respondents were born in 1960 or later.

Fig. 1.3. Median birth year for GSS respondents by decade

Fig. 1.4. Percentage of GSS respondents born before 1933 by decade

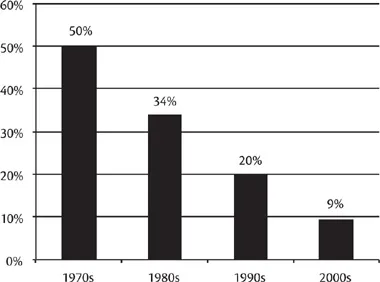

Figure 1.4 provides a dramatic sketch of generational replacement in the GSS by examining the proportion of respondents born before 1933, which is the median for the first decade of data collection. While 50% of respondents in the 1970s were born before 1933, that figure plunges to 9% for the respondents since 2000. The older generations are dying off, and younger cohorts are more important for understanding the nature and trajectory of social life.

Trends in Religious Identification

In the past two decades, two competing grand theories have been the focus of explanation for trends in religious affiliation: supply-side rational-actor theories and the secularization thesis. According to the supply-side perspective, religious denominations are producing a product, and the quality of that product will drive consumer behavior. Proponents of the supply-side “strict church” thesis (Iannaccone 1994) argue that mainline Protestant religious groups are in decline because they fail to offer strong religious products. From this view, liberal religion is mushy and undemanding, offering few (or no) exclusive supernatural rewards and compensators. Supply-side theorists argue that liberal religious denominations are challenged in the provision of basic religious services, since the contributions of committed religious activists are watered down by the presence of shirkers who are not tolerated by exclusivist sectarian groups. In contrast, sectarian religious groups offer clear and exclusive supernatural compensators—promises of heaven only for their faithful. And because sectarian groups exclude the less faithful, their religious activities are also more effective and efficient (Iannaccone 1994). In direct contrast, secularization theories argue that as the United States becomes more secular, religious attachments will become less important. Hence, secularization proponents expect to find that nonaffiliation is increasing, that religious switching is more common, and that more fundamentalist and exclusivist religious groups will decline or only increase through fertility differentials (Greeley and Hout 2006; Hout, Greeley, and Wilde 2001).

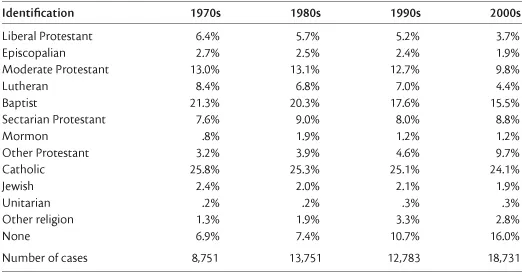

Grand theoretical accounts generally fall short of providing useful explanations for complex sociological processes, in large part because they tend to ignore competing explanations and the diverse set of social forces that impact sociological factors. Table 1.1 presents the distribution of the thirteen religious classifications across the four decades of the GSS. Notably, there is ample support for and divergence from the expectations of both supply-side theories and secularization theories of religious change. First, in line with the expectations of supply-side theorists, liberal Protestant groups hold a declining share of Americans’ religious commitments. In the 1970s, over 6% of respondents identified with a liberal Protestant group, and nearly 3% aligned with the Episcopal Church. In the surveys conducted in the 2000s, liberal Protestant bodies hold the identifications of under 4% of respondents, and Episcopalians garnered 2%. The number of moderate Protestants also fell from 13% of respondents to under 10%, while the proportion of Lutherans plunged from over 8% to over 4%.

Table 1.1. Trends in Religious Identification: GSS 1972–2012

While supply-side theorists have argued that the decline of “mainline” Protestant groups is evidence of the superiority of sectarian religious denominations, the data do not support this side of their argument. Sectarian religious groups are not gaining market share. Baptist bodies have decreased their share from over 21% of Americans to fewer than 16%—close to the combined losses of liberal Protestants, Episcopalians, and moderate Protestants. Other sectarian groups grew modestly from 8% to over 9% between the 1970s and the 1980s but fell back below 9% in the 1990s and held steady in the early 2000s. So while the less exclusivist liberal and moderate religious groups do seem to be experiencing the decline suggested by supply-side theories, their losses are not resulting in gains for the strictly exclusivist Baptist and sectarian denominations.

Looking at other religious groups, table 1.1 shows that the proportion of Catholics in the GSS is remarkably stable over the four decades. Catholicism garnered the identifications of about 25% of Americans in the 1970s, and it held the commitments of 24% in the surveys conducted since 2000. Despite an alarming shortage of priests (Schoenherr, Young, and Cheng 1993) and conflict over birth control, abortion, women’s rights, Vatican II, and a host of pedophilia scandals, Catholicism garners the identifications of the largest plurality of Americans.

Between the 1970s and the 2000s, an increasing proportion of Americans listed their religious identification as “other Protestant.” In the 1970s, just over 3% reported this as an identification, yet in the surveys in the 2000s, almost 10% were Christians with no particular denomination. Both of our grand narratives of religious change could claim victory on this point. Supply-side partisans claim that nondenominational groups are sectarian in their orientation, and hence the growth of this group fits the expectations of strict-church theories. Secularization theorists argue that these “other Protestants” are simply people who do not care enough about religion to identify with any group (Kosmin and Keysar 2006). Later, we will examine the beliefs and religious commitment of these other Protestants to see which of these theses, if either, is more correct.

Mormons, Unitarians, and Jews hold fairly stable across the four decades of the study. There is a notable upward tick in the percentage of Mormons in the 1980s, but this is almost certainly a function of shifts in sampling units of the GSS (sampling units in the GSS are geographic areas from which respondents are randomly selected, and these units change). Because Mormons (and Jews) are regionally concentrated, a shift in regional sampling units could have a considerable impact on their reported proportions.

In line with the expectations of secularization theorists, the proportion of Americans who have no religious identification has increased dramatically since the 1970s. While about 7% of GSS respondents in the 1970s had no religious identification, this proportion more than doubled to nearly 16% in the surveys conducted since 2000. In the surveys conducted since 2000, about the same proportion of Americans were found to have no religious identification as identify with Baptist groups.

The proportion of Americans who identify with other religious traditions has also increased. In the 1970s, only 1.5% of respondents identified with traditions other than Christianity, Mormonism, and Judaism. Yet in the surveys conducted since 2000, 3.1% of respondents identified as Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Unitarian, or other traditions. Notably, that makes these traditions taken together more popular identifications than Episcopalian, Jewish, or Mormon. Non-Christian religion is no longer an esoteric sideline.

Generations and Religious Change

Trends over time are largely a function of generational differences and cohort replacement. The religious character of the United States thirty years from now will be built on the religious identifications of the latest cohorts of Americans, and the members of the World War II generation whose commitments have characterized American religion will all be dead. Yet we cannot be too focused on the absolute differences between cohorts. Religious ties often follow common patterns of aging and development. People often leave religion or switch religious affiliations early in the life course and then return later in life (Wilson and Sherkat 1994), and in cross-sectional data such as the GSS, generations are being compared at quite different points in the life course. Indeed, people born before 1933 were never interviewed at an age less than thirty-nine, and even the youngest among them was at least seventy-nine years old at the time of the 2012 survey. In contrast, GSS respondents who were born in 1960 and later—who constituted 50% of respondents in surveys since 2000—have only been observed at a maximum of age fifty-two, and many were interviewed at ages as young as eighteen. Caution is warranted when making inferences about long-term changes based on generational differences, because age and life-course statuses intersect with generations in repeated cross-sectional data.

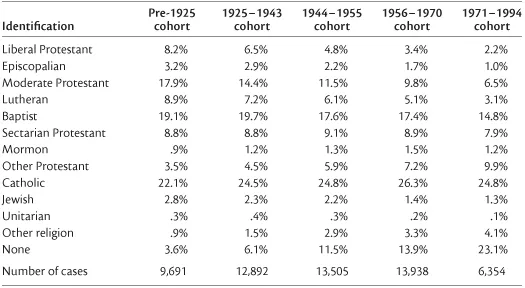

The distributions of religious identifications across generations echo the findings in the trend data and present an even more substantial suggestion of change. Table 1.2 shows that the declines in the percentage of Americans who identify with liberal and moderate Protestant groups are even steeper than was apparent in the trend data. Taken together, liberal and moderate Protestant denominations, the Episcopal Church, and Lutheran groups held the commitments of nearly 38% of respondents born prior to 1925, but this figure drops more than 7% in the 1925–1943 cohort. Indeed, among the youngest cohort born since 1971, only 13% claim an affiliation in any of these traditional “mainline” liberal or moderate denominations.

Table 1.2. Religious Identification by Generation: GSS 1972–2012

While supply-side theorists may be emboldened by the shrinking shares of the more universalistic liberal and moderate denominations, the supply-side expectation that liberal losses lead to gains among exclusivist sectarian groups is inaccurate. As was true in the trend data, Baptists and sectarians also have a declining share of religious identifications in younger cohorts. Baptist groups held the identifications of about 20% of the cohorts born before 1943, but this figure trails off to fewer than 15% of those born after 1970. Other sectarian groups hold steadier, garnering the identification of about 9% of respondents across all the generations born pr...