![]()

1 / “Many negroes in these parts may prove prejudissial several wayes to us and our posteraty”: The Crucial Elements of Exclusion and Social Control in Pennsylvania’s Early Antislavery Movement

America’s antislavery movement underwent a sea change in 1817. The oldest champion of black freedom reported to the annual convention of American abolition societies that year that “the number of those actively engaged in the cause of the oppressed Africans is very small.” Struggling since 1804 to gain a quorum at many of their scheduled meetings, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society blamed this apathy on the retirement of many of its seasoned leaders, combined with “a mistaken impression that the work is nearly accomplished.” Their effort to lead the freed along a path of social conditioning was wilting as well. Instead of unquestioningly accepting white advice and guidance, free blacks were taking their destiny into their own hands and trying to enjoy their liberty on their own terms. The PAS agenda of slowly but steadily fighting for the rights of African Americans while serving as liaison between the black and white communities was failing, and the group was being forced to reevaluate its role in the struggle for freedom.1

That same year the American Colonization Society (ACS) appeared on the national antislavery scene to compete with the gradualists for the spotlight. A close look at the gradualist legacy will illuminate the role colonization would later play in the antislavery movement after the 1820s. Examining the gradualists’ goals and tactics, as well as the challenges they faced by this pivotal year, will reveal much about both movements and their common characteristics, most important of which was a need to oversee and control the free black population. It will also shed light on how gradual abolitionists interacted with the growing free black leadership and how their efforts to limit the black population from the beginning set a precedent for later efforts to remove those who had found asylum in the state.

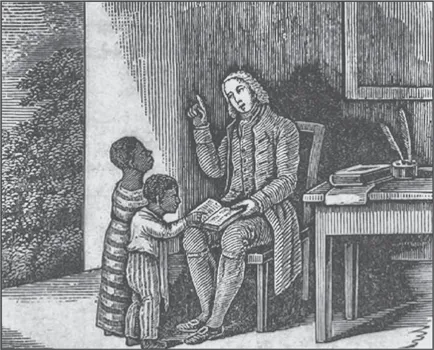

FIGURE 3. Anthony Benezet Reading to Colored Children. (This is a public domain image from Wiki Images.)

Pennsylvania has long been celebrated not only as the birthplace of American liberty but also as the home of the antislavery movement. German Mennonites and Quakers first protested North America’s system of human bondage in 1688, and Philadelphia Quakers banned slave ownership among members in 1774. A year later, they formed the first abolition society in the colonies. This group, called the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, was short-lived. It was resurrected in 1784 with the help of non-Quakers, including Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush. Three years later it became the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Still composed mostly of Quakers, this group took up the crusade to end slavery in the state, and in the meantime, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a gradual abolition act in 1780. Few slaves remained in the state by 1800.2

Though Pennsylvania’s founders made no real effort to prohibit slavery in the beginning, resistance to human bondage began by the end of the seventeenth century. Benjamin Furly, a Quaker agent of William Penn, may have made the first attempt to keep slaves out by proposing a law that would “let no blacks be brought in directly.” According to Furly’s wishes, any slaves who had been brought to Pennsylvania from Virginia, Maryland, “or elsewhere” would have been declared free after eight years. Apparently the agent thought the West Jersey Constitution contained a similar provision, but no such law existed in Jersey, and none was adopted in Pennsylvania. Indeed, 150 Africans arrived in the colony just three years after the Quaker founders and were eagerly purchased and employed in the work of clearing land and building the city of Philadelphia. Between 1682 and 1705 about one of every fifteen Philadelphia families managed to acquire one or more enslaved laborers, and the situation began to bother some Quakers almost immediately.3

The result was an attack on the slave trade, which began with a petition from Germantown in 1688. The Germantown petition, like most protests that followed, appealed to both religious conscience and white self-interest. The authors cited three reasons for opposing slavery. First, it was morally wrong. Not only was slavery a tragic violation of the Golden Rule, it also forced God’s creatures to commit adultery by tearing families apart and making people live together in forced situations in the New World. Also, the moral taint of human bondage discouraged European immigration to the colony. Finally, the system posed a dangerous threat to both Quaker souls and the physical safety of whites. The petitioners asked if slave owners would be willing to violate their nonviolent principles and defend themselves in the face of insurrection. “If once these slaves (which they say are so wicked and stubbern men) should join themselves, fight for their freedom and handel their masters and mastrisses, as they did handel them before; will these masters and mastrisses tacke the sword at hand and warr against these poor slaves?” They added that such a situation was likely and perhaps justified: “Have these negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?”4

A group of Quakers led by George Keith issued a similar protest five years later. This group also used moral and religious justification while appealing to white self-interest. To begin with, the group warned that buying slaves was the same as buying stolen goods, yet worse, since it would be “accounted a far greater crime under Moses’ Law” to buy stolen people than stolen property. Like the previous petition, the Keithians warned fellow Quakers to abide by the Golden Rule, and they quoted Deuteronomy and Exodus to argue against the cruel treatment of slaves and the ripping apart of slave families. They concluded by issuing a stern warning that would appear in many antislavery tracts that followed—all men were created by God, and He would eventually seek justice for His abused children. Turning to the book of Revelation, they cautioned: “Brethren, let us hearken to the voice of the Lord, who saith, Come out of Babylon, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not her Plagues; for her sins have reached unto Heaven, and God hath remembered her Iniquities; for he that leads into Captivity shall go into Captivity.” The solution? Quakers should not buy slaves except to set them free. Those who already had slaves should let them go after they had worked long enough to repay the owner for their purchase price or, in the case of babies born into slavery, the cost of their upbringing. Finally, those who had slaves should “teach them to read, and give them a Christian Education.”5

Other Quakers added their voices to this budding antislavery crusade, focusing mostly on importation. In 1696, the Yearly Meeting cited “several” papers, including those by William Southeby and Cadwalader Morgan, as influencing their decision to advise Friends to “be careful not to encourage the bringing in of any more Negroes.” As a result, the Pennsylvania Quakers wrote to Friends and suppliers in the West Indies asking them to stop sending slaves. This did not work, because two years later the Philadelphia meeting asked members to write to Friends in Barbados and ask them to “forbear sending any negroes to this place, because they are too numerous here.” A group of Friends, including Southeby, drafted the letter, explaining that the Yearly Meeting had concluded that “many negroes in these parts may prove prejudissial several wayes to us and our posteraty” and had agreed that “endeavors should bee used to put a stop to the Importing of them.” If the letter had any effect, it was temporary. In 1711 Chester Monthly Meeting protested the buying of slaves brought into Pennsylvania, and leaders reminded Friends about their 1696 advice. Four years later a Philadelphia Quaker merchant, Jonathan Dickinson, wrote to a relative in Jamaica to “intreat” him “not to send any more” slaves because “the generality of our people are against any coming into the country.”6

Banning the importation of slaves was central to this early phase of the antislavery movement. Chester Monthly Meeting played a large role in this endeavor, petitioning the Yearly Meeting in 1711, 1715, and 1716, but because 60 percent of Yearly Meeting leaders owned slaves, they only cautioned Quakers against the practice. The petition drive continued, however, with Quaker farmers and artisans calling for a ban on the further importation of slaves several times between 1711 and 1729, and the Yearly Meeting strengthened its early statement in 1730. Again, this was merely a caution rather than a directive.7

The Pennsylvania Assembly tried to provide a stronger response to these pleas. They attempted to prohibit slave importation by levying duties beginning in 1700. In most cases the Crown repealed such taxes, but the colonists eventually found a way to avoid this interference by passing acts and not telling the government until enough time had passed that they had already become law. After the famous New York slave insurrection of 1712, the assembly passed a high import tax of twenty pounds per slave, but by 1729 the tax had dwindled to two pounds. In 1761 they raised the tax to ten pounds, and when this tax reached twenty pounds again in 1773, the traffic in human labor in Pennsylvania halted.8

These efforts mirrored similar action taken throughout the North American colonies as British slave imports to these colonies grew from 37,400 in the period between 1701 and 1725 to 116,900 in the years between 1751 and 1775. South Carolina and Georgia began trying to limit imports in 1698, and the former tried to prohibit the slave trade altogether in 1760, but the Privy Council forbade this action and reprimanded the governor. North Carolina imposed prohibitive duties in 1786, and Virginia made similar efforts from 1710 to 1772 when the House of Burgesses tried to petition the king to stop the trade to their state. In these planting colonies, opposition to the trade was most often based on fear of insurrection, as historian W. E. B. Du Bois showed long ago. He claimed that similar efforts were made in the farming colonies of New York, Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania because the system was not as profitable in those states, but the fear factor applied in these colonies as well. Finally, Du Bois contended that opposition to the slave trade in the New England colonies was “from the first based solely on moral grounds, with some social arguments.”9

Motives for focusing on the slave trade before attacking slavery itself were complicated. Many Quakers realized that traffic in human beings relied on force and thus violated their principle of nonviolence. Also, concentrating on the trade allowed these abolitionists to express their qualms about slavery yet earn respect for moderation. At the same time, many believed that without fresh slave imports from abroad, slavery would eventually die out. In contrast, calling for immediate release of all slaves would have branded them as radicals and offended those whose consciences they hoped to awaken, so they used limited, short-term goals in order to make their overall agenda of emancipation more easily attainable. Finally, by arguing against the slave trade, Quakers managed to ease their consciences without causing financial problems for the slave owners in their ranks.10

At the same time, the focus on importation reveals an element of self-interest. Even the most benevolent whites feared the growing black population and the threat of insurrection. Stopping the trade as soon as possible limited the threat by keeping the black population relatively small. Quaker abolitionists attacked slavery at times of high importation because the larger the enslaved population, the greater the danger. The legislature shared the fear and joined the effort to limit importation. In seeking import duties, they listed as their main motivations concern for the spread of disease, alarm at the news of slave revolts in other areas, and dread over the prospect of an increase in the number of runaways and petty criminals.11

Both the legislature and abolitionists agreed that the enslaved population needed to be kept as small as possible because the system presented a number of threats to white society. First, if the system was indeed morally wrong, then it must at some point invoke the wrath of God. Indeed, many Quakers saw the Seven Years’ War as evidence of God’s displeasure, and they renewed their antislavery efforts in response. Also, slavery encouraged owners to be lazy and greedy, two major areas of contention among Quakers. As if that were not bad enough, it put whites in peril. What if, as the Germantown group warned, slaves did rise up? Whites would either be killed or forced to disregard the church’s nonviolent tenets in order to defend themselves. Though they hoped to eventually do away with slavery altogether, Quaker abolitionists had to first focus on the short-term solution of ending the trade. If they succeeded, when they turned to general emancipation, they would be dealing with as small a population of freedmen as possible.

Anthony Benezet’s works illustrate this connection. Benezet was the quintessential Quaker abolitionist. He joined the crusade in 1750 and soon began publishing antislavery tracts. He ultimately played a large role in bringing abolition beyond the bounds of the Quaker meeting and into the larger society. He convinced the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to accept abolition, and he managed to persuade them to publish his 1754 Epistle of Caution and Advice, Concerning the Buying and Keeping of Slaves. He also influenced non-Quaker abolitionists in both Britain and the colonies, including Granville Sharp, John Wesley, Thomas Clarkson, and Benjamin Rush. And when the state legislature was considering the gradual abolition bill, he personally visited each member to seek support for the measure.12

Like the petitioners before him, Benezet saw the slave trade as both morally wrong and dangerous to white interests. He described the slave trade as murder and insisted that Europeans deliberately caused African nations to war with each other and take captives for the market. Not only did this encourage murder, it was also “manstealing” and a gross violation of God’s law, and it provided a flimsy excuse for participating in the trade. Countering arguments that the captives were better off toiling in the Americas than being executed at home, he asked if fighting a just war would make it acceptable for the English to enslave and sell the French. He also used firsthand accounts to describe in sad detail the violence of the trade and the abuse of slaves, pointing out that blacks were just “as susceptible of Pain and Grief” as whites, and calling on his readers to put themselves in the slaves’ shoes. He asked, “What Distress can we conceive equal to the Alarms, and anxiety, and Wrath, which must succeed one another in the Breasts of the tender parents, or affectionate children, in continual Danger of being torn one from another and dragged into a state of cruel Bondage!” To further illustrate his point about family destruction, he described a tragic case in which a family lost its father figure and provider to the trade, showing how slavery hurt not only those taken captive but also those who managed to avoid getting kidnapped.13

Whether they realized it or not, slavery put whites in great peril. Benezet pointed out that the system made slave owners feel themselves “more consequential” than others and encouraged them to become lazy and greedy. At the same time it left laboring people and tradesmen feeling “slighted, disregarded, and robbed of the natural opportunities of Labour common in other countries.” As a result it discouraged white European immigration. But these problems were fairly minor. The real threat lay in the form of retribution at the hands of either God or the enslaved. Because of the violence and theft inherent in the system, it greatly displeased God, and he would eventually make things right. Benezet, who introduced the argument that many of the calamities the colonies were facing were products of divine retribution, warned that it would only get worse. Slaveholders must free their slaves and help them find jobs “not only as an Act of Justice to the Individuals, but as a Debt due, on Account of the Oppression and Injustice perpetrated on them … and as the best means to avert the judgements of God.” Either God or the enslaved would eventually punish not only the slave owners but also their white neighbors, and he pointed to the unrest in Barbados to show that the larger the black population became, the greater the danger.14

Benezet proposed a four-step plan to end slavery and thus prevent such a disaster. First, “all farther Importation [must] be absolutely prohibited.” For most this would have been enough, because this step solved the issue of violence inherent in the trade. For Benezet, however, it was just the beginning, since keeping slaves was as morally wrong as owning them. Therefore, once the slaves already in the colonies had served long enough to repay the owner for money he had spent on their purchase or rearing, they should be freed. Like indentured servants, slaves guilty of willfully neglecting their duty could be required to serve additional time. He proposed that the freed be treated in a manner consistent with English poor laws, suggesting that they be “enrolled in the County Court, and obliged to be a resident during a certain Number of Years within the said County, under the Inspection of the Overseers of the Poor.” Benezet’s last step called for restitution in the form of land grants. He argued that giving the freed land would make them taxable citizens and give them a stake in society.15

For Benezet’s plan to work, the black population would have to be small, and before they could be freed, slaves would have to be carefully prepared. For this reason, Benezet joined fellow gradualists in pushing first for an end to the slave trade by supporting the efforts to tax imports. Aware of public concern over the idea of emancipation, he ad...